The British Concession and the First Years of the Treaty Port

The Foreigners of Hankou before the founding of the Concessions

Prior to the opening of the port in 1861, Hankou had long served as an intersection and destination for westerners in Central China. As early as 1696 a Roman Catholic mission had been established in the city, and though it was expelled around 1700, successive movements of Jesuits and later Lazarists settled in and spread Catholicism in Hankou and throughout Hubei (Rowe, 1984: 44-45). Russian tea merchants, traveling across Siberia, interacted with Chinese intermediaries and likely visited and stayed in the city as well. While the opening of the port and the establishment of the British Concession initiated an influx of foreign residents, up until the 1890s their numbers remained minute compared to the Chinese city’s 500,000 inhabitants and changed frequently with commercial seasons and business fortunes (Rowe, 1984: 40). Thus, in many ways the concession’s true transformative power in the immediate aftermath of its founding lay in the creation of a permanent foreign space from which British and international influence could permeate and transform Hankou.

Treaty of Tianjin and conflict over the opening of the concession

Hankou was included amongst the ports opened by the 1858 Treaty of Tianjin and the 1860 Convention of Peking which concluded the Second Opium War. Lord Elgin, the British negotiator of the Tianjin treaty, embarked on a trip down the Yangtze in December 1858 to survey sites for potential treaty ports (Dean, 1972: 74). At that time Hankou was still recovering from the destruction wrought by Taiping occupation and subsequent Qing campaigns, however the city’s rapid reconstruction, its still bustling commercial sector, and favorable location on the Yangtze drew Elgin’s attention (Neild, 2015: 98). On March 11, 1861 an expedition under Admiral James Hope reached the city and Harry Parkes determined the site for the future concession. Lying just north of the Chinese city, the boundaries extended up the Yangtze 2750 feet and inland 1210 feet, occupying in a patch of land which included a suburb where around 2500 families resided (Dean, 1972: 75). Intense and lengthy negotiations ensued between Lord Elgin, the British consul William Gingell, Huguang Governor General Guan Wen, and Hanyang prefect Liu Qiyu over the lease for the concession, the pricing of lots, and the payments to be issued for evicted Chinese residents, concluding finally in September 1862 (Dean, 1972).

The Bund and houses under construction, Hankou

With the Hankou bund and its adjacent buildings still under construction, this image was likely taken just prior to or during 1863, when the bund was completed. This makes it the earliest image of the Hankou bund we've found thus far.

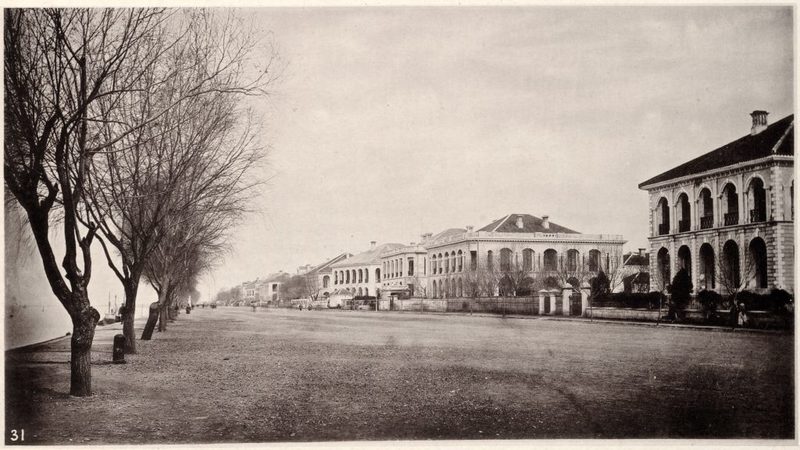

Hankou Bund, 1865

Dated 1865, this image depicts the completed bund with its row of plane trees still small.

Hankow (Foreign Settlement)

A 1871 photograph of the Bund shot by John Thomson. This is the negative and therefore Thomson was likely shooting from similar position as the 1865 photographer.

The Concession Takes Form

By the end of 1861 ten British firms, two American, and one Prussian had established themselves in Hankou, with the foreign population sitting at 40 (Neild, 2015: 99). As lots within the concession were quickly snapped up by merchant companies, many operating out of main offices in Shanghai, other foreigners began purchasing land outside of the concession along the Yangtze to its south and even across the Han river in Hanyang. However, as early as 1862 and 1863 these exclaves were abandoned in favor of housing inside of the concession, consolidating the foreign community while further isolating them from the Chinese city. While land was initially available only to British tenants, this regulation was lifted in 1964 and nationals of any treaty power were allowed to settled in the concession (Lewis, 1910: 693). The concession’s low-lying location and the Yangtze’s frequent floods necessitated the construction of a bund, which was funded by wharfage dues and completed in 1863 (see images above). The firms which purchased property along this bund constructed walled compounds and large trading houses similar to those found in Shanghai. Hankou’s early construction boom and the eagerness of foreign arrivals was largely tied to the port’s proximity to major tea growing regions in Hubei and Hunan, which brought the attention of both established companies and “commercial adventurers” from across the West (Neild, 2015: 100). Early entrains into the market were experienced firms like Jardines and Heards interested in long-term engagement, along with newer companies like Mackellar & Co. which sought quick riches off the boom. Foreign representatives of these companies flowed in and out of Hankou with the seasonal trade in tea, as the British Consul Chalconer Alabaster described in 1879, “for three months of the year the settlement is crowded and busy, while during the other nine it is deserted by three fourths of its residents” (Rowe, 1984: 46). Long wooden quays which extended from the bund outside of shipping companies like Butterfield and Swire (a later arrival) were bustling during these three months with Chinese workers carrying packaged tea onto ships for export down the Yangtze. As many foreign companies approached Hankou’s tea trade with an all-or-nothing attitude, the port’s trade swelled rapidly from 1961 to 1964 as new companies moved in trying to make their mark. This attitude also led many foreigners to treat their Chinese vendors extremely poorly, trying almost anything to make fast profits, and Chinese tea merchants retaliated in kind, often substituting quality product for cheap tea laden with sawdust (Rowe, 1984). Both these approaches were unconducive to a long-term, healthy business environment, and by the late 1860s the Hankou tea rush had all but burned out. Competition between British merchants, the Chinese Tea guild, and local Chinese government continued up until the 1880s and 90s, when tea sales declined significantly as British preferences shifted away from Chinese teas to those grown in India and Ceylon. The resulting economic slump took over Hankou’s businesses, causing a mass foreign exodus from the port that left the international population around 100 (Neild, 2015: 103). By 1900 no tea was being shipped from Hankou to London, although Hankou’s foreign businesses had, starting in the 1890s, moved on to more profitable ventures in industrial production.

Butterfield and Swire frontage on the Yangtze River, Hankow

This photograph was taken between 1906-1907 by G. Warren Swire of Butterfield and Swire. The low water level makes the quay used to load ships anchored in the Yangtze more visable.

Butterfield and Swire hulks etc. from hong, Hankow (汉口)

Another photograph by Swire from between 1906-1907, illustrating the loading of steamer ships.

Loading goods at Butterfield and Swire hulks, Hankow

The porters carrying cargo onto this steamer were among the few Chinese inhabitants of Hankou allowed in the concessions, a policy which would not change until the descruction of the Chinese city in the 1911 battle of Yangxia.

Life in the Early British Concession

From the 1861 founding of the concession to the peak of the early Hankou tea trade in 1864, Hankou’s population grew from 150, mostly British nationals along with some French and Americans, to 300. Many of these migrating residents shared residences in Shanghai, and brought customs, entertainment preferences, and architectural designs from there and abroad. During this early period the Hankow Club was established as a social venue for all the foreign residents of the concession, regardless of foreign nationality (Chinese were still prohibited) (Neild, 2015: 100). A municipal council was also founded, along with a Chamber of Commerce a few years later to represent unified foreign trade interests. Amongst the foreign residents of Hankou horse racing was very popular, and organized racing started in 1863 with summer and autumn meets. A year later, in the area northeast of the concession, a race track was laid out and began operating in partial association with the Hankow Club, becoming one of the concessions’ most popular social destinations. While such social institutions were prohibitive of Chinese membership, a select few concentrated on cultivating it, namely foreign missions. The Catholic Church, already active in Hankou and operating a missionary hospital there in the native city, expanded its operations to Wuchang during the late 1800s (Rowe, 1984: 47). The founding of the British concession further brought the first Protestant missionaries to Hankou, first Griffith John and Robert Wilson of the London Missionary Society (LMS) in June of 1861 followed by Josiah Cox of the Wesleyan Methodist Missionary School (WMMS) (Chang, 1999: 423). The LMS group settled in the concession, while WMMS set up in the native city, and both worked in cooperation to evangelize through “street-preaching, book-selling and church services. However, due to limited staffing educational and medical projects could not be commenced until the end of the 19th century.

Hankou’s Other Foreigners

Amongst the British concession’s other foreign residents were members of Hankou’s Russian population, who had dwelled and worked in the city even prior to the concession’s establishment in the manufacture and exportation of brick tea to the Russian market. While tea bricks in this period predominantly traveled overland through Siberia to meet Russian customers, by 1861 there were two Russian vessels calling in Hankou, and four Russian tea merchants operating in the concession in 1866 (Neild, 2015: 101). Between 1873 and 1892 members of the Russian community in the British concession established four factories which used modern machines and assembly lines instead of traditional wooden presses to create brick tea, making them Hankou’s first industrialists and some of its richest foreign residents (Eiermann, 2005: 41). Despite relying on the British concession for land and housing, many of the Russian residents of Hankou resented the British dominance on capital and in the movement of tea out of Hankou, a grievance which would later justify the Russian concession. Another substantial foreign group which arrived after the opening of Hankou were Japanese nationals, who settled in the Chinese city but had limited access to foreign social enterprises like the Hankou Club. Japanese immigrants started arriving in 1874, and most worked as private traders, a notable exception being Arao Kiyoshi (Rowe, 1984: 48). Coming to Hankou in 1885, Arao founded a shop which sold imported books, foreign medicines, and Japanese manufactured goods and was managed by seven Japanese and five Chinese assistants. Despite covering as a merchant, Arao’s real intention was apparently to encourage the development of Pan-Asianism in Central China while relaying commercial intelligence to his compatriots in Shanghai and Japan. Notwithstanding of these efforts Arao met with very little success, even with his closer proximity to the city’s Chinese residents relative to other foreign inhabitants

The Chinese City and the Concession

Regardless of the necessity of Chinese labor for the operation of the English concession’s industries, Chinese individuals were prohibited from settling in the concession and most were not even allowed to enter (Rowe, 1984: 49). The missionary Henrietta Green justified this “cruel necessity” with “it seems rather hard to keep the Chinese off, but if it were not so, ladies could not walk out alone at night” (Rowe, 1984: 49). The few Chinese who were permitted to dwell and work with lower restrictions in the concession were domestic servants or compradors under the service of trading firms, but they were largely emigrants from other treaty ports, most predominantly Shanghai, and had come to Hankou with their employers. Residents of Hankou’s native city found work as coolies, dockhands, warehouse workers, and as industrial laborers in Hankou’s early factories, however even their numbers were limited, being described in 1888 by the British Consul Clement Allen as numbering around 2,000 (though it should be noted the late 1880s and early 1890s was a low period for Hankou’s tea trade). Indeed, this demographic picture presents the early British Concession, when compared with the constantly busy Chinese city, as a contradictory space. Where a population of, at most 300 foreigners, attempted to assert its economic, militaristic, and symbolic power over an enormous native commercial hub from white, palatial manors isolated from the rest of the city (and other foreign centers more broadly) and largely abandoned during lulls in trade (Rowe, 1984: 45). A maritime customs commissioner in 1865 described the situation as such: “It may not be out of place to remind Foreigners that here they have not yet attained the position of their countrymen in the South, but that they are still in old China, where they are comparatively little known or appreciated, except by a class in whose interest it is to keep them isolated from the mass of the population” (Rowe, 1984: 49).

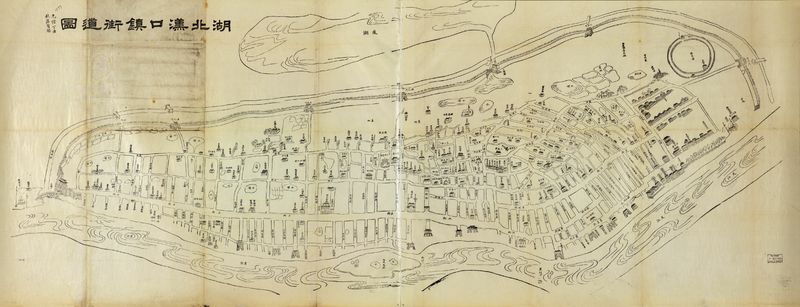

Residential Map of Hankou town, Hubei

This map, produced in 1877 by the Hubei Boundry Company (湖北藩司), depicts the English settlement (upper right) as part of the larger Chinese city, distinguished by its unique architectural style and right-angled streets.