Self-Strengthening Wuhan

While narratives of foreign factories and industry in Hankou are dominated by imperialistic opportunism and asymmetric relationships between foreign managers and Chinese employees, the factors involved in the creation of native Chinese industry are more diverse. In many cases factories were the product of intersecting forces – ranging from government sponsorship, nationalistic sentiments, foreign knowledge and technology, and native entrepreneurship. This section primarily centers around three key individuals – Zhang Zhidong, Song Weichen, and Sheng Xuanhuai – who, motivated through a combination of self-strengthening spirit, desire for prestige, and the opportunity for massive profits, shaped the foundations of Wuhan’s future industry.

To understand the origins of the Hanyang Ironworks and Arsenal – the first heavy industrial plant in Wuhan and among the first in all of China – it is necessary to go back to Zhang Zhidong’s time as Governor General of the Liangguang provinces (or the provinces of Guangdong and Guangxi). Appointed to the position in the summer of 1884, Zhang oversaw the logistical support for Chinese forces fighting in the Indochinese front of the Sino-French war (Kennedy, 1973: 157). Zhang was frustrated again and again by the inefficiencies of the provincial arsenal system based around the Guangdong Arsenal, which necessitated the purchase of arms and military advice from the British in Hong Kong. During this period, he developed a keen awareness of the necessity of high-quality, mobile weapon systems, constructed using materials obtained nationally without the interference of foreigners, and the importance of military knowledge and knowledge institutions to coordinate both combat and support. Zhang conveyed these concerns in a three-point platform concentrating on the development of personnel, production of weapons, and exploitation of natural resources, which he laid out in a long memorial sent to Beijing on August 7th 1885 (Kennedy, 1973: 158). To confront the failures of the arsenal system, which relied on coastal cities like Fuzhou which were devastated during the Sino-French War, Zhang Zhidong proposed an interior railway system that would be less vulnerable to attack, and could connect weapons manufactured safely in the interior with coastal provinces threatened by invasion (Lee, 1989: 57). When this plan was accepted by the Qing government in 1889, Zhang was transferred to the governor-generalship of Hubei in order to coordinate the construction of the railway. Once in Wuchang, the provincial capital, Zhang set about arranging the province to fit his more flexible vision of self-strengthening – which involved combining education with manufacturing and other industries to encourage economic development and increase government revenues.

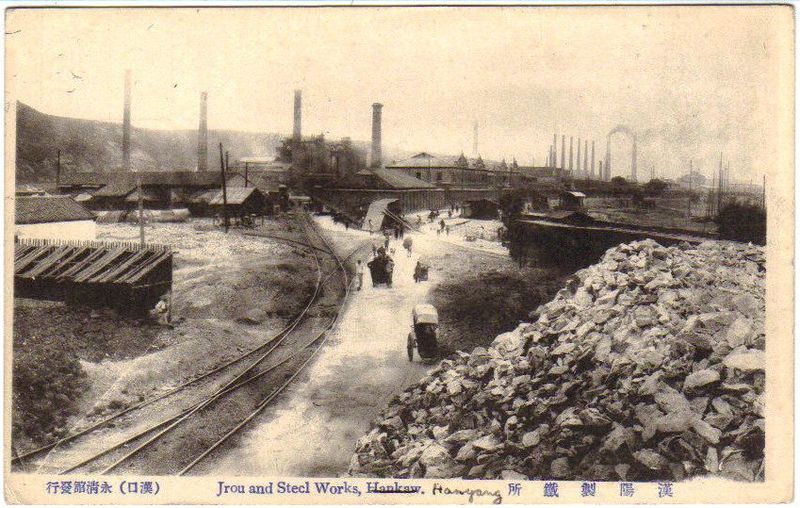

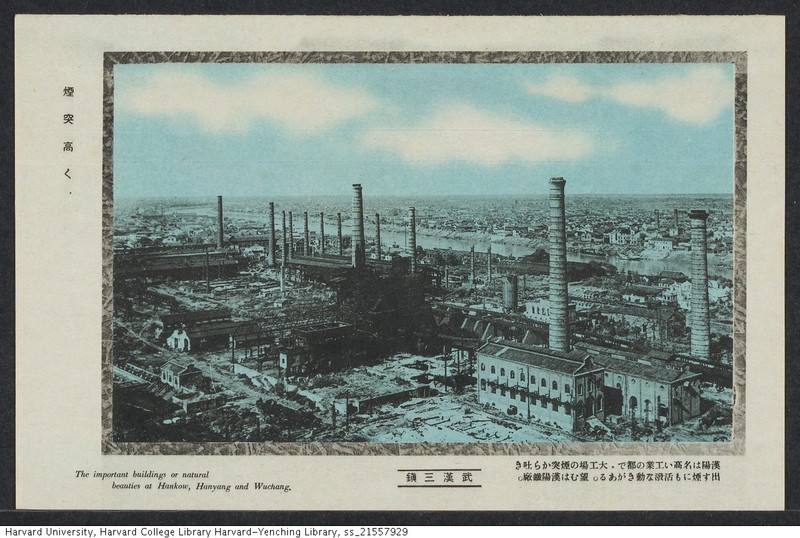

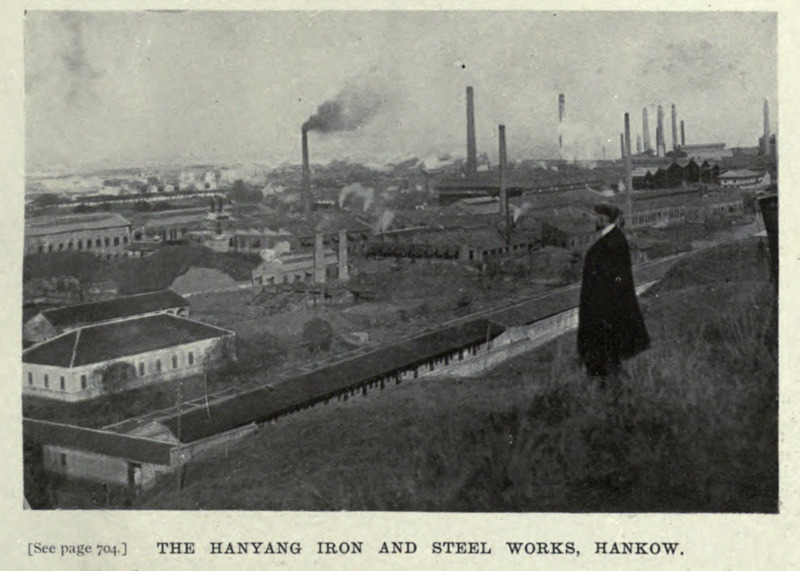

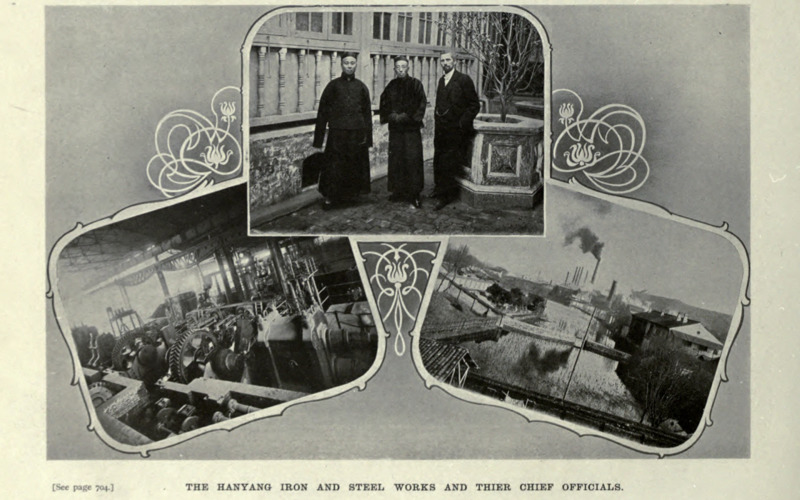

Before departing Guangzhou, Zhang had been planning for the establishment of an arsenal on par with the one located in Shanghai, which combined an ironworks capable of large-scale steel forging and an arsenal for machining that steel into weapons. With some political maneuvering Zhang arranged for the funds and machinery already purchased for Guangzhou to be transferred to Hubei province, protecting his existing funds for the creation of the Bei-Han Railway. On December 23 1890 the foundations were laid and construction on the Ironworks began in 1891 at the base of Hanyang’s Turtle Mountain, a long ridge running parallel the Han river which separates Hanyang from Hankou (Neild, 2015: 109. Feng, 2013: 113). Construction was completed in 1893, and expensive machinery purchased in Britain was moved into the factory. The factory would draw on nearby coal and iron ore mines However, the Ironworks was not an immediate success, and for three years of its functioning it remained a drain on the Hubei government’s funds, until in 1896 Zhang sold the works to Sheng Xuanhuai (Lee, 1989: 59). Sheng’s purchase of the Ironworks was to some extent a favor for Zhang, who in exchange put him in charge of the new Chinese Imperial Railway Administration, which would play a major role in the construction of the Bei-Han line and others to come. Sheng then sent for a team of 24 European (mostly Belgian) engineers to examine the project and attempt to improve production, who found issues of corruption and inefficiency due to the facility’s layout (Neild, 2015: 109). Little was done to resolve these problems issues until the plant was closed in 1905 to be completely refitted, and afterwards a large team of foreign technical advisors was hired to guide further development. The Ironworks grew rapidly after this, soon employing a team of over 40 foreign technicians and over 3,000 Chinese workers and fulfilling orders for the railway and the neighboring arsenal (Feng, 2013: 113. Neild, 2015: 109). The Hanyang Ironworks was, at its time, China’s only mechanized ironworks and, with a daily output of 40-50 tons, produced the most steel in all of Asia (Feng, 2013: 113).

The Hanyang Arsenal was established next door, further down the Han river, and was completed in 1894, in part due to the syphoning of funds into the ironworks (Kennedy, 1973: 176). The machinery was purchased from the famed Krupp Arsenal in Germany, and was selected for the production of Mauser single-shot rifles, along with Krupp cannons, gun carriages, and ammunition (Kennedy, 1973: 176). By 1898 the arsenal had “rifle, bullet and artillery factories, steel tube mills, and a gunpowder plant” (Feng, 2013: 113). These facilities were operated initially by more than 1,200 workers, many of them artisans brought in to Hubei from Hong Kong and Shanghai, and by 1904 their numbers exceeded 4,500. By 1909 the arsenal’s production had come to surpass all other similar operations in China, having produced 130,658 rifles, 985 cannons, 61,776,554 bullets, 905 gun carriages, 971671 artillery shells, and over 270,000 pounds of smokeless gunpowder (Feng, 2013: 114).

While such industries established under Zhang normally flowed from state-enterprises into private firms with state-backing, other companies established by Chinese entrepreneurs drew their origins from both the private and public sectors. One example of a highly successful private firm was the Sui Hua Match company. Opened in 1897 in the Japanese concession, the Sui Hua Match Factory was one in a chain established by the Ningbo merchant Ye Chengzhong (Courtney, 2018: 79). The Hankou branch was headed by Song Weichen, another Ningbo native and established match mogul in his own right, would go on to become one of Hankou’s leading Chinese businessmen. The factory which would make Song rich was by 1908 producing a half-a-million boxes of matches every day, and due to their popularity poet Luo Han described their ‘foreign fire’ as having extinguished the traditional practice in Hankou of passing embers from one stove to another (Neild, 2015: 110. Courtney, 2018: 79). Conditions in factories like Sui Hua, which generally employed women and children, offered poor wages for deplorable conditions, where workers were exposed to white phosphorus, a chemical that raised rises of fires and was also poisonous. Despite this, desire for kerosene lamps and cigarette consumption made matches an incredibly lucrative industry, and by 1922 the Sui Hua Match Factory was the largest producer in China (Neild, 2015: 110).

The scope of Zhang Zhidong’s self-strengthening movement was not limited to the arsenal however, and over the course of his 18 years in Hubei he would participate in developing numerous other industrial projects. To facilitate the production of materials at the Ironworks and Arsenal while building his vision of a New Army for China, Zhang established a considerable number of schools oriented towards Western-style education and subject fields (Feng, 2013: 119). These schools, mostly based in Wuchang, formed the early foundation of Wuhan’s modern education system, and specialized in developing and disseminating industrial knowledge. Under Zhang’s leadership a silver mint was also established in Wuchang in 1893, and a copper mint was added later with similarly quality machinery. These new centers of currency distribution played a major role in stimulating trade and long-distance transactions, furthering Wuhan’s role as a major commercial center. Due to the demand for cotton goods in the Chinese market and abroad, Zhang also ordered the establishment in 1891 of a number of cotton mills which opened under British and Swiss management in 1893 (Neild, 2015: 110). Four corresponding bureaus were created within the Hubei government for yarn, burlap, silk, and cloth, each producing in designated factories around Wuhan. These companies, initially state-run, were transferred to trusted Chinese companies that shared in the Hubei leaderships’ goal of national self-strengthening through economic empowerment. Their shared productive capacity would weather the storm of the 1911 Revolution and Wuhan would emerge, along with neighboring foreign firms, as a textile center only comparable to Shanghai in capacity. Under Zhang’s supervision numerous other state-run or state-supervised emerged in Wuhan, these included “the Baishazhou Paper Mill, Nanhu Tannery, Hubei Felt Factory, and Lanling Street Hubei Model Factory in Wuchang; the Hubei Needle and Nail Factory, and the Hubei Official Brickyard in Hanyang; and the Mechanized Tea Mill, Chenjiaji Paper Mill, and Qiaolou Workhouse for the Poor in Hankou.