Tea Bricks and Hides: Hankou's Early Industrialization

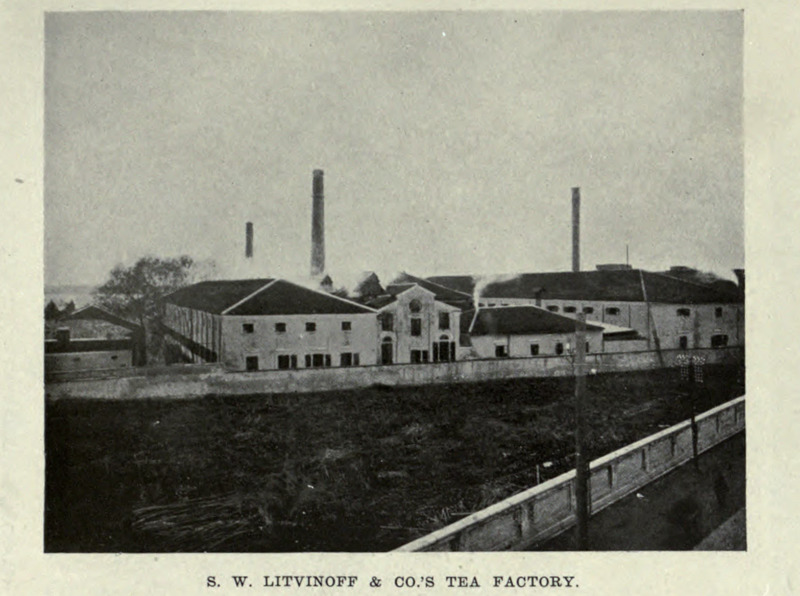

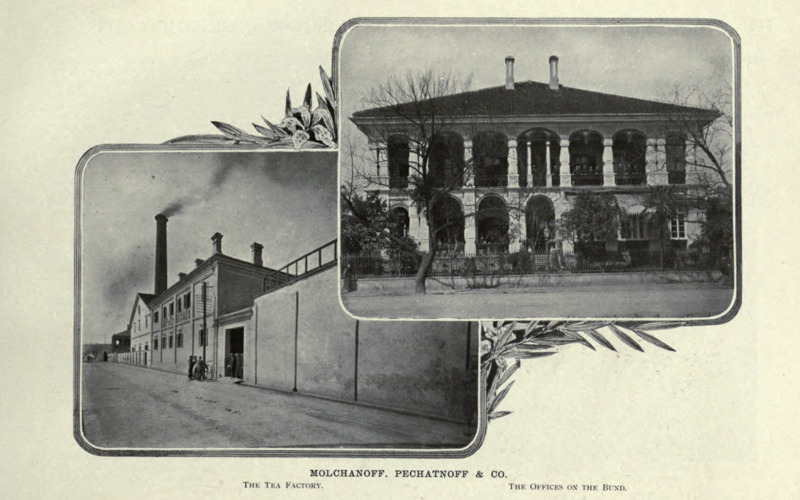

While Hankou was amongst the largest commercial ports in China long before the establishment of the concessions, its trade was largely centered around the exchange and production of raw materials, handicrafts, and foodstuffs. Hankou’s first factories, operating under mechanized production using a labor force assigned specialized tasks, were brick tea producers established by Russian traders. Brick and tablet teas are distinct from the higher-end leaf tea, shipped by British and American firms to customers in London. Brick tea was made by “grinding broken leaves and tea dust into a fine powder, which was steamed and pressed in a wooden mold,” while tablet tea consisted of whole leaves instead of powder and was not steamed to avoid loss of flavor (Neild, 2015: 102, Lewis, 1908: 712). Brick tea was then stored in light, bamboo baskets (while tablet tea was wrapped in foil) and sent up the Han river westward on the overland route to Russia. As brick tea was sought traditionally by Russian clientele – in part due to the long history of tea trade between Russia and Hankou – it was produced primarily in Russian-owned factories based, prior to 1895, in the British concession and managed by the substantial Russian community that had settled there. The first of these factories was established in 1873, followed by three others in 1873, 1878, and 1892, and employed Chinese laborers (numbering around one hundred in prior to the expansion of production brought by the Treaty of Shimonoseki) (Rowe, 1984: 49). Among those making fortunes of the production and export of tea bricks was J.K. Panoff, a relative of Tsar Nicholas I, who operated Mochanoff Pechatnoff & Co., one of Hankou’s largest brick tea factories. Panoff was an active member of Hankou high-society, participating as a member of the Russian Municipal Council and having commissioned a number of notable buildings (Lewis, 1908: 712). Russian manufacturing began to accelerate in the 1890s, and after a 1891 visit by Czar Nicholas II to Hankou tea bricks began to be shipped by steamer up the Yangtze to Vladivostok, where (after the completion of the trans-Siberian railway) they were put on trains for Moscow. By 1908 the Mochanoff Pechatnoff factory in the British concession was employing around 2000 Chinese workers, and was equipped with high-end machinery to maximize production. The brick tea industry, along with the Russian population of Hankou, peaked in 1916, with nearly 30,000 tons exported (Neild, 2015: 102). However, the 1917 revolution and ensuing civil war severely constrained the industry’s market and potential for export, and following the ascendance of the Bolsheviks and their severing of business ties in China, exports ceased completely. By 1922 the only remaining firm was Mochanoff Pecatnoff & Co., operated by a skeleton crew stilled headed by Panoff, who apparently was reluctant to leave the enormous house he had constructed on the French concession’s Bund

Molachanoff. Pechatnoff & Co.

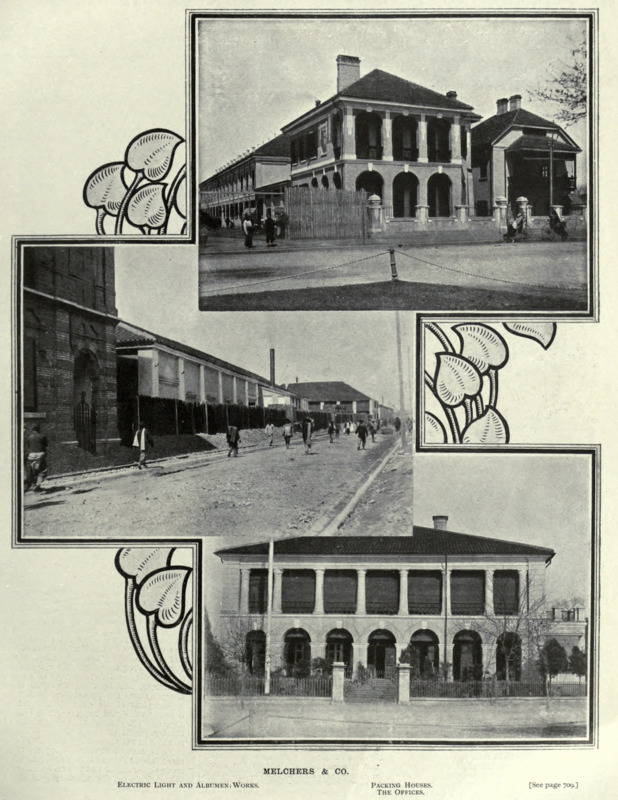

The Tea Factory and Bund office of Molachanoff Pechatnoff & Co. as of 1908, both located in the British Concession. After the Bolsheviks cut business ties with China in 1917, Molachanoff Pechatnoff & Co. would be the last brick tea manufacturer left in Hankou.

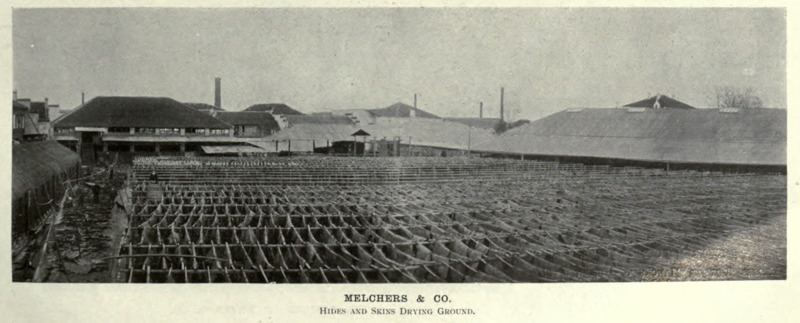

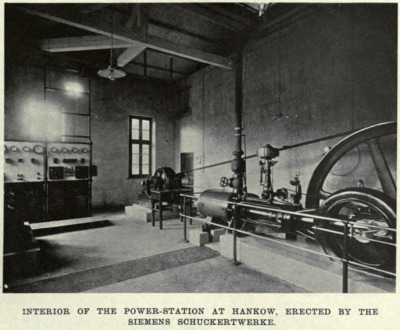

While Hankou’s earliest foreign factories failed when they were cut off from their customer base, later arrivals to Hankou’s industrial trades were much more successful, in part because they sought to capture local markets as well as export sales. Prior to the treaty of Shimonoseki which opened the flood gates for foreigners interested in factory operations, foreign companies established in the concessions had been primarily trading firms which dealt in exporting goods up the Yangtze. However, following the treaty, many of these pre-established companies in Hankou sought to expand and diversify their portfolios by entering into newly opened industries. An excellent example of this was Messrs. Melchers & Co., a German export company that had been established in Hankou since the mid-1880s (Neild, 2015: 104). When the German concession was founded in the late 1890s, Melchers & Co. purchased a large slot of land to build a hide-drying yard as an extension of their already profitable offices in the British Concession (Wright, 1908: 709). Hides were exported themselves along with other low-end products like tallow, wax and pig bristles to local markets and to some extent abroad, and were mostly produced in the German concession up until the British concession permitted their production in the 1898 extension (Neild, 2015). Melchers & Co. also established an albumen factory, a product made from egg-whites and used in printing and photography (Neild, 2015: 104). In 1907 Melchers & Co. opened a steam plant which fueled their electric light instillation that powered both the albumen factory and the entire German concession’s electrical grid, eventually being extended to the Japanese concession as well (Neild, 2015). Similar companies grew and thrived in the concessions, managed by small foreign staffs and employing a largely Chinese work force.

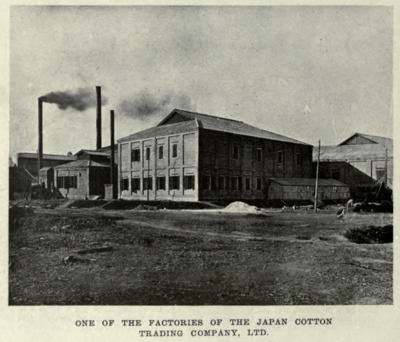

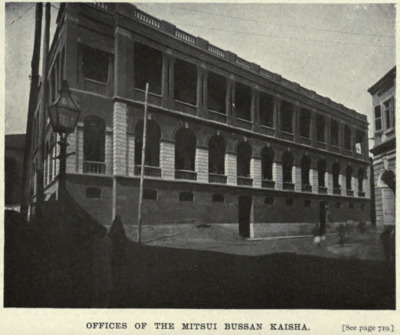

The opening of the Beijing-Hankou railway line in 1905, a project which was deeply intertwined with both Western business interests and Chinese self-strengthening efforts, further fueled industrial growth in the concessions and elsewhere in Wuhan – with the local press counting over 84 factories in 1907 (Neild, 2015: 109). While a number of British firms had ventured into similar sectors as German companies, a large part of Hankou’s light industry sector was dominated by Japanese firms. Japanese firms like the Japan Cotton Trading Co., The Mitsui Bussan Company, and the Mitsu Bishi Company operated many of Hankou’s foreign owned cotton factories which processed cotton into yarn and pressed cotton seeds into oil (Neild, 2015: 106. Wright, 1908). The prominent Japan Cotton Trading Co. opened in Hankou in 1906 and operated a number of factories both in the Japanese concession and across the Han river in Hanyang. Many Japanese enterprises found success by placing plants in parts of the native city, particularly in Hanyang and Wuchang where there was little competition for wages from Western firms.

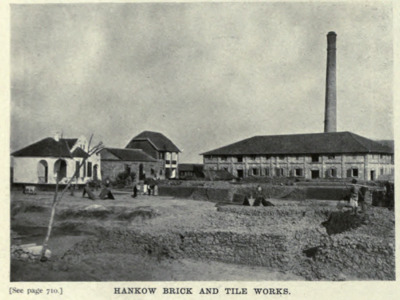

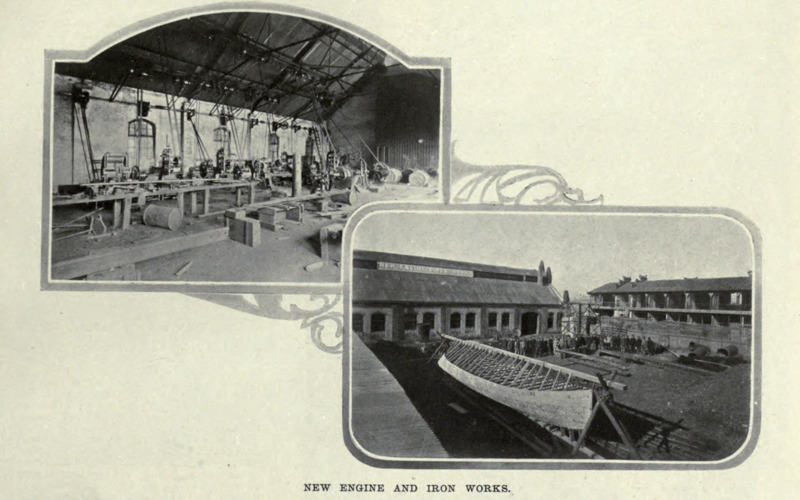

Targeting Chinese consumers was a key part to succeeding in interior Hankou, as the case of the tobacco industry clearly illustrates. While tobacco was already locally produced in Hankou, the industry leader British-American Tobacco (BAT) saw the opportunity to expand profits by encouraging local farmers to use American seeds which could be turned into more popular American cigarettes. BAT quickly established a large factory in the German concession, which by 1911 was the largest of its kind in China, producing some ten million sticks a day (Neild, 2015: 110). Despite the encroachment in 1922 by the Nanyang Brothers Tobacco Company, BAT’s aggressive advertising campaigns maintained its industry position and by 1931 it employed over 2800 workers in two factories and produced some seven billion cigarettes a year. The rapid growth of industrial production in Hankou further facilitated the growth of industries and trades which produced the necessary machinery and goods to maintain factories. The Hankow Brick and Tile Works, located along the banks of Han river to the west of the native city, satisfied the enormous demand for building materials to construct new factories and Western style buildings in the evolving concessions (Wright, 1908: 710). Firms like the Shanghai Machine Company, which opened its Hankou branch in 1906, and the New Engine and Iron Works, founded in 1903 in the German concession, satisfied the need for modern machinery in factories, construction projects, and lighting plants. Oil and kerosene, necessary products for powering generators, ships, and lighting the city, were supplied initially by the Standard Oil Company of New York, which established itself in Hankou in 1895 (Neild, 2015: 110). Shell joined them in 1901 with new tanks and a facility for tinning kerosene. They were followed by Texas Co. in 1921, who in ten years dwarfed their competition with a facility for storing some 15 million liters and capable of producing over 5000 cans every day.