Social Life in Hankou

From Hankou’s wealthy to its working classes, spaces available for entertainment and recreation were constantly changing as the city evolved, expanded, and, periodically, was destroyed. Hankou was renowned for its racetracks, one for the city’s Chinese inhabitants and another for foreigners, and hosted numerous tea gardens and other entertainment establishments. In this section, we trace narratives of social life in Hankou through the lens of the spaces they inhabited, paying particular attention to how class and nationality divided the city’s recreational areas and practices, and how overtime these borders took on new forms. This section focuses on the unique period of time in Hankou’s history where foreign and native spaces for entertainment cohabited and interacted with each other, often mirroring and building off the other’s advancement.

Prior to the opening of the city in 1861, Hankou’s status as a bustling market town brought with it considerable demand for entertainment spaces and areas for social gatherings. One location where entertainers congregated was known as Houhu, or literally “Back lake” (Li, 2012: 85). This area was located to the north of the city, beyond the wall which would be built in 1864, and was described as half downtown and half countryside (“半居街市半居乡”). Along the thoroughfares surrounding Houhu and a number of smaller lakes one could find a wide range of entertainment styles performed by individuals on the street, ranging from music, to dancing and juggling. At certain points outdoor, open-air stages were constructed for the performance of operas and other songs. Hankou’s status as a center for the salt trade brought with it a number of Yangzhou salt merchants, who constructed a number of gardens in the city where they hosted private gatherings. The city’s guild halls, which also acted as major centers for commercial interactions, also provided more private entertainment venues (Li, 2012: 85). The Shanxi-Shaanxi guild was one of the city’s most prosperous, and it contained a number of stages for various kinds of performances. Teahouses were also very common in the city both prior to and following the opening of the port, and acted as a space where merchants could enjoy entertainment and music while focusing on their conversations regarding business or politics. These establishments continued to proliferate as the city’s trade grew rapidly around the turn of the century, in 1909 there were 441 tea houses in greater Wuhan, with 250 in Hankou alone, and in 1918 that number had grown to 696.

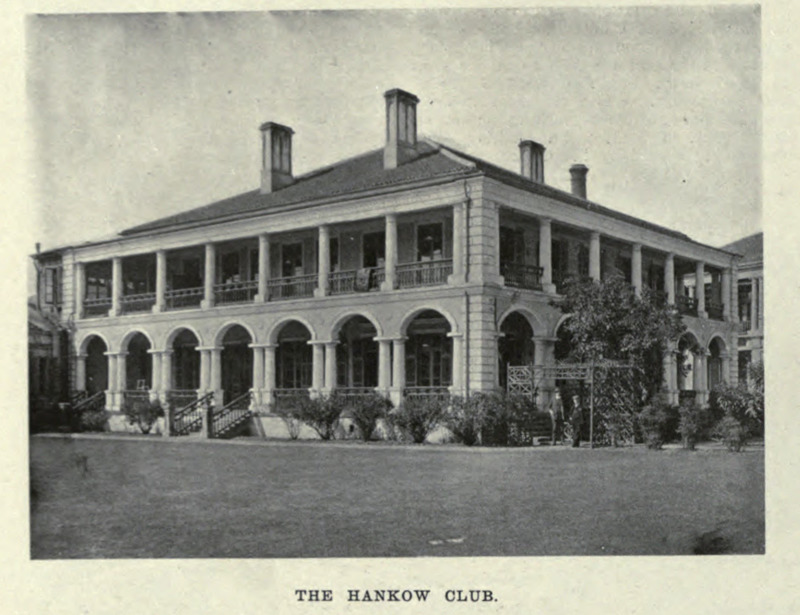

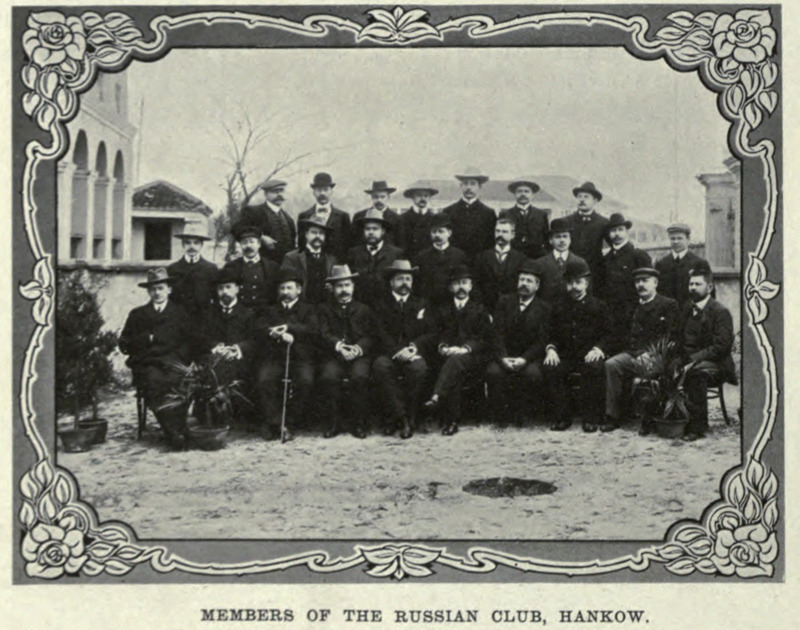

The establishment of the British concession in 1861 brought foreign entertainment customers to Hankou which sought out spaces that both indulged their desires to explore the Far East while satisfying their needs for the comforts of home. Among Hankou’s earliest Western institutions – founded in the first year of the concession’s existence – was the Hankou Club, which provided a gathering point for all of Hankou’s foreign residents while excluding all locals (Neild, 2015: 100). Well known from the start for its excellent facilities, the Club acquired a new building and grounds sometime around the turn of the century (Neild, 2015: 113). This new, two-story building was surrounded on both levels by open verandas, providing members with a view of the well-kept and spacious grounds which surrounded it. The club offered attendees access to its renowned library, one of the largest and most important collections of European literature on the Far East in China, which contained over five thousand volumes in English and German along with recent editions of periodicals and journals from China and abroad (Wright, 1908: 700). The Hankou club also contained “five billiard tables, a bowling alley, card room, bar, and restaurant” all equipped with electric lights and fans (Wright, 1908: 700). Membership in 1908 included 200 of Hankou’s foreign elites, many of whom were drawn to the club as no similar location existed in the upper reaches of the Yangtze, despite the existence of several other concessions. In addition to the more “cosmopolitan” Hankou Club, other foreign communities also created their own social organizations based around their national roots. The largest of these other clubs was the Russian Club, which was founded in 1898 and hosted around 40 Russian members, along with 35 visiting members drawn from Hankou’s foreign upper-stratum. The club building itself also offered a library, as well as reading, drawing, and card rooms, a large dining hall, and a bowling alley – all also equipped with electrical lighting and fans, “everything that can make for the convenience and comfort of the members” (Wright, 1908: 700). The Russian Club was also host to the Russian Amateur Dramatic Club, whose performances – being performed in Russian – were likely rather exclusive to the rest of the city’s community (Neild, 2015: 113). Similar national clubs were hosted for Hankou’s French, German, Japanese, and Belgian populations – although the German club was converted into a club for customs service officers after the concession was retroceded.

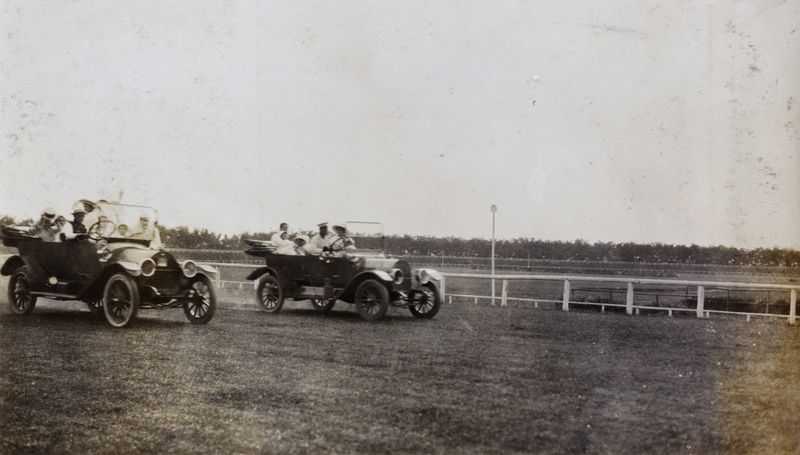

Another popular social activity amongst Hankou’s foreign and native populations alike was attending horse races. The first horse race was held in April 1863, and a pattern of spring and autumn meets was established (Neild, 2015: 100). A race course was laid out to the north of the concession in 1864 and is very prominent in early maps of the city. When the French concession was founded atop the land which the track occupied in 1895, the French offered to pay for a new site and land was acquired to the northwest of the concessions in 1899. In 1905 the Hankow Race Club and Recreation Ground was opened to the foreign population and became enormously successful. By the 1920s the Grounds also contained two golf courses, cricket and football fields, twelve tennis courts, a bowling green and a clay-pigeon shooting range. The Club also had a large swimming pool which, after it froze over in the winter, was boarded over and became a ballroom dance floor. Within ten years of its founding the Club had a membership of over 300, and despite the wide range of nationalities represented there it was still incredibly exclusionary to Chinese membership. In 1906 the Chinese-managed Huashang track was established to the north of the native city to rival the Hankow Race Club’s, demonstrating a shared passion for horse racing amongst both Chinese and foreign audiences (Mackinnon, 2000: 163

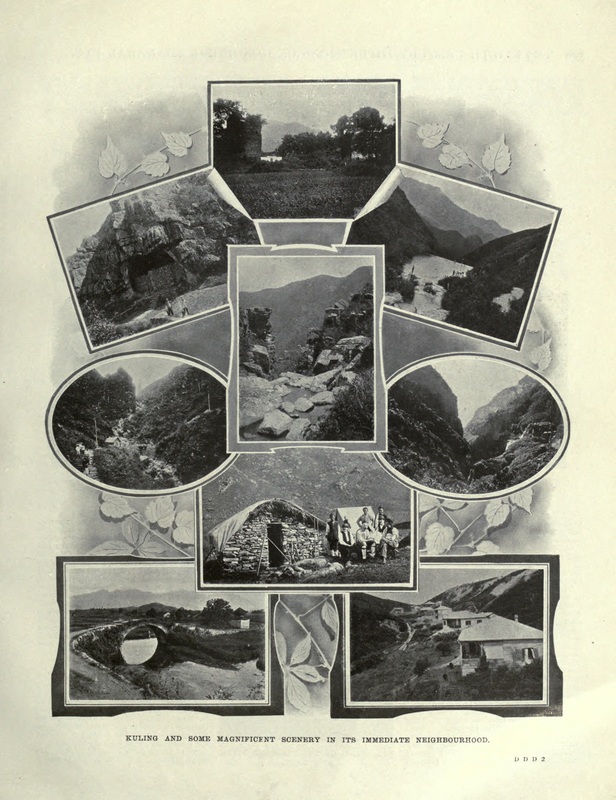

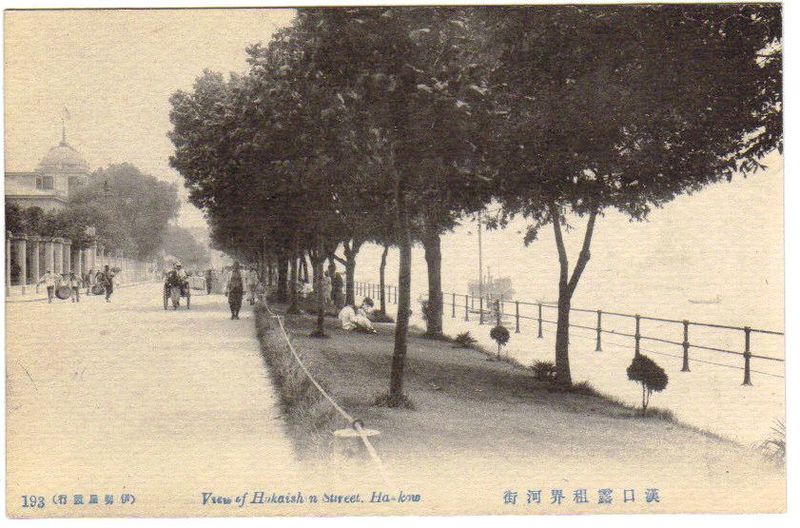

Amongst Hankou’s foreign residents and its wealthier Chinese citizens, entertainment could also be found in expeditions beyond the city. A 1908 guide to Chinese treaty ports describes how, in the height of the summer’s heat from June until September, Hankou residents escape to Kuling, a settlement located some 3000 feet above the surrounding countryside (Wright, 1908: 698). The guide describes the scenery as “extremely picturesque,” remarking on the way the Yangtze flows beneath the hills and the landscape is dotted with “ruins” of ancient Chinese temples and monasteries. Kuling was described as being home to a substantial foreign settlement composed of “numerous pretty bungalows, good roads, a comfortable hotel, and, indeed, every convenience calculated to promote the comfort of a visitor and to make his stay as pleasant as possible” (Wright, 1908: 698). This site was apparently the product of significant investment by residents of Shanghai and Hankou, who would ride six hours by sedan chair to participate in this community, rented for the convenience of foreigners from the Chinese government. Photographs taken by foreigners in Hankou capture a similar obsession with wild and ancient China, depicting decaying stone temples and elaborate towers as well as hunting expeditions and picnics. Outdoor spaces within the city were used for recreation as well, and as the concession was opened to Chinese residents these spaces became shared amongst all the city’s population. Photos capture people lounging on the grass underneath the Bund’s long line of plane trees, as well as fishing off stretches of sandbar in the Yangtze.