A Class Background of Wuhan since 1949

Although the Wuhan incident itself would not occur until 1967, to understand why a city of some 2.5 million people would suddenly erupt into violent factionalism, it is necessary to examine the origins of those factions in long-standing social tensions. To begin, consider the residential patterns of Wuhan during the Communist period leading up to the 1960s. While Wuhan had traditionally been divided into the three cities – Hankou, Hanyang, and Wuchang – as the cities drew closer together in the first half of the 20th century, the divisions within those cities, their particular districts and class-lines, began to be more distinctive to the arrangement of class in Wuhan as a whole. Central Hankou became known as the Jianghan District, and in keeping with the city’s traditions was largely a commercial area with some small-scale, traditional industries (Wang, 1995: 24). The Jiang’an and Qiaokou districts on the outskirts of Hankou were where the city’s industry was concentrated. Across the river in Hanyang, devastated during World War II, some newly developed industries had re-emerged by the city was largely devoid of cultural and educational institutions. The central city of Wuchang, the area which used to be fortified by the city’s wall and the extended suburbs to the north, was Wuhan’s cultural and educational center – housing “Colleges, universities, scientific research institutions, and literature and arts organizations. The Wuchang district also housed a number of large, modern industries, and to the city’s east – known as the Qingshan District – two giant companies, Wuhan Steel and Iron and First Metallurgical Corporation, occupied almost the entire area. Class divides within the city followed the lines of these districts, with Qiaokou, Hanyang, and Qingshan housing industrial workers; Jianghan by non-proletarian laborers, the non-intellectual ‘middle class’, and former capitalists’ Wuchang by intellectuals, and civilian and military functionaries serving the provincial government and the Wuhan Military Region (WMR); and Jiang’an by an amalgamation of the city’s different peoples (Wang, 1995: 24).

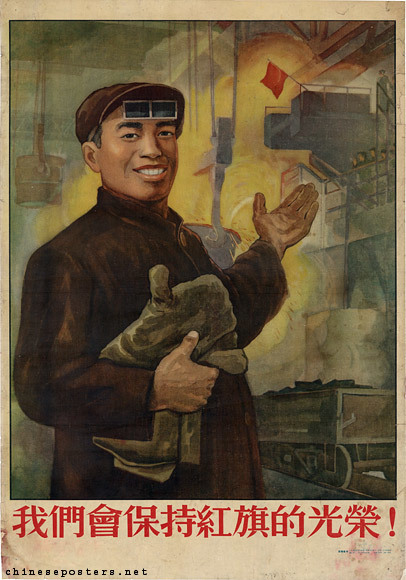

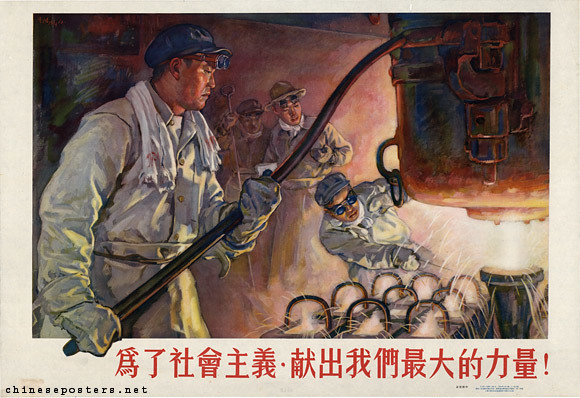

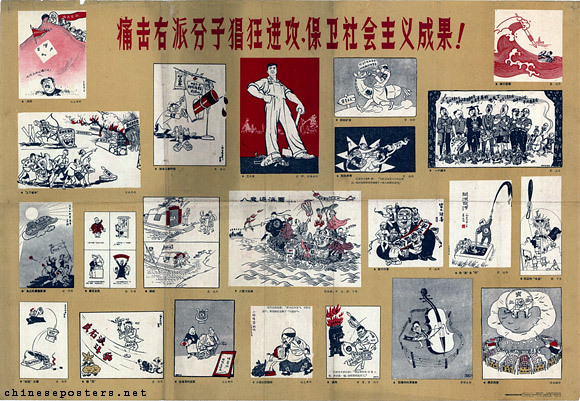

While a principal goal of the proletarian revolution which had swept China under the CCP in the late 1940s was the abolition of private ownership and a hierarchical orientation of labor relations, the asymmetric distribution of work continued into the Communist regime, just under different class labels. First identified by Zhou Dajue, an assistant professor at Beijing Aeronautical Engineering Institute, in 1957, a new class dynamic had emerged in China with cadres at the top and workers on the bottom. This division had been largely fueled by cadres capacity to leverage their leadership positions into personal advantages, while workers were left with little opportunity to alter their social position and outlook (Wang, 1995: 25). Despite the divide between workers and cadres, this growing gap in systemic benefits was largely obscured by conflicts within these two groups up until the 1960s. Cadres were split between a political bureaucracy, administrative and managerial personnel, and technocrats. Most political cadres had arisen from poor or working-class backgrounds through revolutionary activism and military service, obtaining jobs preforming vital ideological tasks, often without formal educations. Despite the CCP’s desire to promote as many of these individuals into positions of authority as possible, it was impossible to adequately fill managerial and technocratic posts with solely uneducated but patriotic cadres. The party thus chose to integrate many former capitalists and ex-Nationalist military officers into the ranks of the new government’s administrative personnel, and despite CCP efforts to promote as many workers to such positions in following years, many former capitalists held their jobs despite their poor class backgrounds (Wang, 1995: 28). During the Hundred Flowers movement, many of these members of the managerial cadres, along-side intellectuals, criticized the promotion of political cadres due to their poor educations, and insisted that China’s future would depend on greater expertise, not political zeal. A fear of impending social closure, in which the political cadres would be excluded from political power, instigated the political cadres to weaponize the developing social institution of class background (which had been developing in the cities through successive anti-rightist campaigns) to disenfranchise the former capitalists and intellectuals before they themselves could be excluded (Wang, 1995: 31). Workers had similarly stratified into three categories: activist, backwards element, and middle-of-the-road. Where one fell in this system was in part a product of one’s job performance. Activists were those who had attained status through their hard work and contributions to production, fitting the model of ideal worker created through ideology and propaganda (Wang, 1995: 33). Before 1956, backwards elements were those who frequently fell behind on production quotas and were viewed to be failing to pull their weight. After 1957 political participation and performance became more significant, and those who were “indifferent to politics” were equally excluded and faced harassment from their superiors. As social life grew increasingly political in the 1960s, pressure was placed on the middle elements to prove their dedication through activism or face becoming labeled as a backward element. This increasing polarization pulled the strongest activists forward, even up into the political ranks of the cadres, while backwards elements became increasingly discriminated against and excluded. Backwards elements, in response, strove to be critical of the establishment within their work units, de-emphasizing political action in favor of more personal freedom (Wang, 1995: 37).

Despite the existence of a cadre-worker class divide, during the 1950s and early 60s there was no property-owning class, and while incomes and economic rewards differed slightly between groups it was not noticeably significant (Wang, 1995: 42). The government, particularly political cadres, were largely concerned with the continuation of class divisions into further generations through the age-old social-elevator of education. This led to the implementation of a series of both positive and negative affirmative action policies aimed to encourage more children with proletarian class backgrounds to enter education while discouraging those from old elite families (Wang, 1995: 47). These policies were not particularly successful however, and children of former elites still constituted the majority in China’s better universities. Such policies further contributed to frustrations across class groups which saw the educational system to be discriminating against them. Out of these class divisions two distinct social alliances began to form across cadres and workers in the 1960s. The first of these was between the political cadres and the activist workers. Political cadres dominated the political structure but resented the still-high standards of living attained by the old-elites-turned-cadre, who leveraged personal connections and, at times, rental income from former properties to sustain their lifestyles (Wang, 1995: 49). Activist workers, despite being the subject of significant praise as symbols of the proletariat, despised the continued disparity between their social standing and material circumstances. The professional cadres, or former capitalists and intellectuals, saw the political cadres as undeservedly powerful and aimed to move towards a more meritocratic system which might advantage them. They were joined with their allies, the backwards elements, by a common enemy in the political cadres and activist workers, who had targeted both with anti-rightist campaigns and whose established dominance stood in the way of freedom for the outcasted backwards elements.