Of Workers, Students, and Rebels

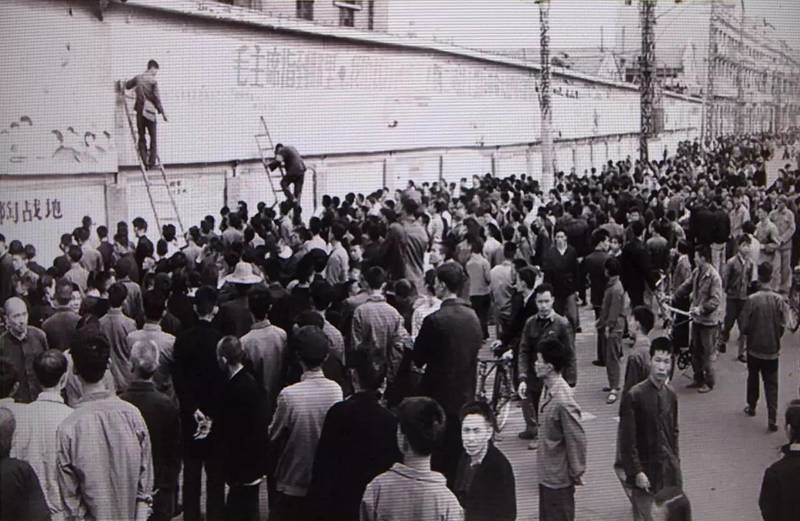

The Cultural Revolution arrived in Wuhan on two wavelengths. The first was through an announcement by Wang Renzhong, the First Secretary of the Hubei Provincial Party Committee (HPPC), who, in April 1966, returned from a conference held by Mao in March to announce the beginning of a Cultural Revolution (Wang, 1995: 55). On the 25th of April, Wang explained to other elites the necessity of routing out bourgeois intellectuals from cultural and educational circles. To the political elite of Wuhan there was nothing alarming about the announcement, and it gave them good reason to pursue campaigns against their rivals amongst the professional cadre. This campaign grew in steam throughout the spring, but had little impact on the city’s working classes as it was essentially viewed as just another anti-rightist campaign which would reinforce the existing political-class structure with political cadres at the top. However, Mao’s intensions for the Cultural Revolution were very different, and on June 1st ordered that the contents of a poster written by Nie Yuanzi and six other teachers and students at Beijing University be broadcast over the national radio network. The poster’s contents criticized ‘representatives of the bourgeoisie within the party,’ and indicated Mao’s implicit permission for millions of Chinese citizens to criticize party authority. This message, however, was slow to be received, and certainly within these early months established party bureaucrats did not believe Mao intended to turn the entire system on its head. However, some students in Wuhan caught wind of Mao’s message, and took it upon themselves, having had little experience with political activism in the past, to write up and distribute Big Character posters criticizing the Wuhan party establishment (Wang, 1995: 56). Posters first appeared on June 2nd at the Wuhan Institute of Topography, “accusing their school Party committees of lacking seal in their support of the campaign to criticize ‘anti-Party and anti-socialism black gangs’ (Wang, 1995: 56). Party officials, shocked by this challenge, retaliated quickly by ordering schools in Wuhan to “seek ‘unity of students’ thinking,’” but many other students had already followed in suit, growing in ambition as well by targeting officials in the Wuhan Municipal Party Committee (WMPC). Wang Renzhong’s campaign in response targeted some 254 students who were labelled as “sham-leftists,” indicating to students that activities against the central Party authority would not be tolerated. Instead, Wang sent out new directives to schools and work units to seek out rightists in their midst, and these brought prosecution down on the traditional enemies of the political cadres – intellectuals, those with bad class backgrounds, and bad elements in work units (Wang, 1995: 59).

A speech delivered to high school students by Deng Ken, the younger brother of Deng Xiaoping and deputy mayor of Wuhan:

If the children of workers and peasants don’t have a better chance for higher education, how can we claim that our society is a socialist society?...We must carry out the CCP’s class line in high school and college admission, giving students from five good categories more chances... As far as those from the exploitative classes are concerned... the only way for them to overcome the influence of bourgeois ideology and to thoroughly remold themselves is to become ordinary laborers and, best of all, to go to the countryside. It is wrong for them to demand an equal opportunity.” (Wang, 1995: 63).

This often was manifested in work teams, sent into schools and work units by the Party to coordinate the search for rightist elements. The effect of these work teams on individual work units later shaped the dynamics of rebel organizations, with new leadership brought in by the work teams being attacked by the previous establishment, while the previous establishment was simultaneously targeted by rebel organizations formed from those who had been repressed before the entrance of the work team (Wang, 1995: 67).

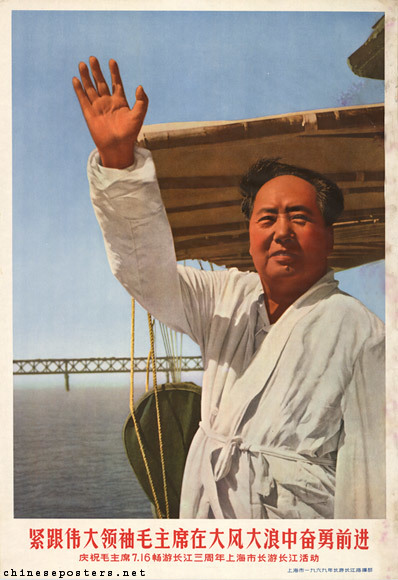

Closely follow the great leader Chairman Mao and forge ahead courageously amid great storms and waves - Celebrate the Shanghai movement to swim the Yangzi river to commemorate the third anniversary of Chairman Mao's good swim in the Yangzi river on July the sixteenth.

A poster celebrating Mao Zedong's swimming of the Yangtze nearby Wuhan, a preformance of personal strength done just prior to his launching of the Cultural Revolution.

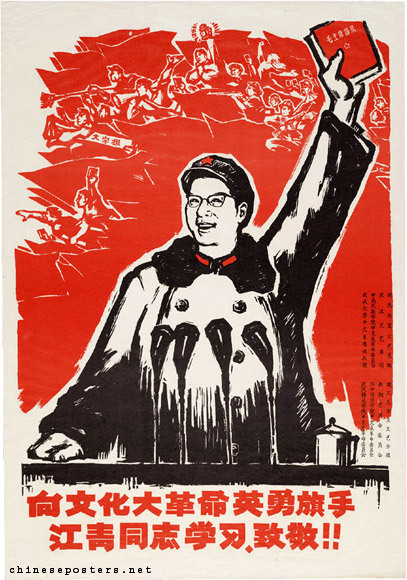

Learn from the valiant standard-bearer of the Great Cultural Revolution, comrade Jiang Qing, and pay her respect!

Learn from the valiant standard-bearer of the Great Cultural Revolution, comrade Jiang Qing, and pay her respect!

Circumstances began to change however after Mao returned to Beijing from a visit to Wuhan on July 18th, and condemned – much to the surprise of Wuhan’s political establishment – the work teams that had proven integral to their strategy. Simultaneously, Mao began to cut out the “old rules of the game,” by permitting free mobilization, allowing individual citizens’ their own judgement, and providing free mobilization as a weapon against political elites who might stand in the way of ‘revolutionary initiative’ (Wang, 1995: 69). These commands also heralded the rise in Beijing of the Red Guards. Born out of the presentation of one million young militants in Tiananmen square on August 18th, Red Guard organizations sprang up in schools all across Wuhan, raising further concern about the direction of Beijing’s policy amongst Wuhan’s political establishment. Despite their concern, Mao’s clear promotion of the Red Guards limited the interference of the HPPC and WMPC to attempts to cultivate party support amongst the students. In Wuhan as elsewhere, Red Guards became an exclusive group, accessible only to those from “the five red categories” or “children of workers, poor and lower-middle peasants, revolutionary cadres, revolutionary soldiers, and revolutionary martyrs” (Wang, 1995: 73). Others from bad class backgrounds were encouraged to adhere to Red Guard principles, and some joined the ”Red Periphery,” an adjacent organization, but were excluded entirely from participation in the prestigious and increasingly powerful movement. However, in Wuhan (unlike in Beijing) students from red backgrounds constituted a minority in the higher education system, and growing discrimination fueled resentment amongst those students prohibited from joining the movement (Wang, 1995: 75). Overall, the Red Guard organizations as a whole had the broader social impacts in Wuhan of normalizing the organization of peoples around their own interests and permitting trans-unit activity and organization, breaking out of the work unit mold.

A former senior high student from an intellectual family recalled one night in late August 1966:

That night, an all-school gathering was held on the football field at my school. Everyone was required to participate. In the past, whenever there was an all-school gathering, the students always sat with their classmates. This time, however, classes had been disbanded and the students were divided into three blocks. Those with good class backgrounds sat in the front. They shouted loudly, ‘A hero’s child is a brave man, while a reactionary’s child is a bastard’ and sand “East is Red’. We, the middle-origin students, sat in the middle singing ‘Sailing the Seas Depends on the Helmsman’. The poor- or bad-origin students were ordered to be quiet and to sit at the back. Many teachers from exploitative family backgrounds were dragged to the rostrum and forced to sing ‘We are Monsters and Ghosts’. That night marked a turning point in my life. I had sensed discrimination for quite some time before the Cultural Revolution. Back then, the discrimination had been subtle. But now the veiled discrimination was replaced by a public humiliation, and the dormant contradictions among students by open confrontation. The students literally split, though no one dared to protest at that moment. We were filled with fury. (Wang, 1995: 75).

In August a new wind began to blow from the top, this one encouraged students to travel between Beijing and the provinces as a part of “exchanging revolutionary experiences” or chuanlian. This movement had a number of significant effects. Students from Wuhan began moving in massive numbers to Beijing and other provinces, while Red Guards, organized and radicalized in Beijing, began to move to Wuhan (Wang, 1995: 76). As the chuanlian movement from late August to early September was restricted to good-origins students, many of those who left their home cities were conservatives, who had been active at home mostly in maintaining the status quo by repressing those from bad-class backgrounds. However, as students moved into areas beyond their home cities, they were no longer inhibited by their associations with the area’s standing political institutions, and instead sought to rebel by following Mao’s instructions and criticizing the establishment (Wang, 1995: 81) Thus, many of the Beijing students that arrived in Wuhan came from conservative backgrounds but felt uninhibited when launching critical campaigns against Wuhan’s political establishment. With the full backing of Mao behind the students, the HPPC and the WMPC were put on the defensive, trying to appease students and maneuver around them in order to stay firmly in power. These chuanlian students in Wuhan had the further effect of organizing opposition forces against the Wuhan political establishment. As students who had left Wuhan returned to the city in late September more radicalized, they brought with them awareness that Red Guard organizations no longer had to be monopolistic, and there could be multiple Red Guard groups per school. These new, minority Red Guard organizations called themselves Mao Zedong Thought Red Guards, and represented an alternative to the children of the conservative establishment that had monopolized the original Red Guard factions of each school. Mao Zedong, aware that the early Red Guard groups were stand-ins for the status quo he sought to overturn, issued an announcement in early October which would shift the dynamics of the Cultural Revolution in the favor of the minority students and away from the establishment (Wang, 1995: 80). Manifested in a statement from the Cultural Revolution Study Group, Mao declared that the wrong political labels which had been enforced on students over recent months must be removed, that recent classifications were invalid, and that those who had been mistreated must be rehabilitated and provided compensation (Wang, 1995: 80). This move encouraged those who had been victimized to demand authorities face consequences for their actions, and openly dismissed the continuation of the political cadres’ dominance. The result was the shattering of the HPPC and WMPC’s authority in Wuhan, and the mass proliferation of rebel organizations as a result. Simultaneously, in October children from middle and poor class backgrounds were finally allowed to go on chuanlian, where in new cities they were able to shed their class labels and came to realize the true targets of the Cultural Revolution were capitalist roaders in the CCP, not their parents. They brought these ideas back with them when they returned to Wuhan in November and December, further fueling the growing radical organizations in schools (Wang, 1995: 82). The newly established Mao Zedong Thought Red Guards were largely organized around a resentment of the exclusionary practices of the original Red Guards, and thus were both open to any student regardless of class background and more bent on radically transforming the political structure maintained by the original Red Guards and their families.

Soon schools were almost cleanly divided between the conservative Red Guards, who had begun coordinating between schools in September, and the rebel Thought Guards, who established the Second Headquarters on October 26 as their organization. Due to internal disputes however Thought Guards from three colleges – New Central China Institute of Technology, New Hubei University, and New Central China Institute of Agriculture – refused to join the Second Headquarters and instead formed their own collation referred to, after their schools, as the “Three News” (Wang, 2006: 243). Workers rebel organizations developed soon after, beginning in work units and extending outward to associate with larger organizations that had grouped together at the city level. The first of these city-level rebel organizations was the Workers’ Headquarters, being established on November 9th in Wuchang. Simultaneously another group was coalescing in Hankou, the Workers Rebel Headquarters, which declared itself on December 8th. This was followed on the 12th by the September 13 Corps, a group which grew out of the Qingshan District’s enormous industrial factories – the Wuhan Iron and Steel and First Metallurgical Corporation (Wang, 2006: 243). As Mao was clearly weighing in behind rebel groups at the end of 1966, conservative organizations were slow to form and lasted for much shorter periods of time. The Federation of Revolutionary Laborers, Wuhan’s first workers association drawn from the ranks of the “activist” class, was founded on December 2nd but failed within the first week of the new year. Even though large organizations like these would prove to be powerful forces, they were also rife with internal tensions and often acted as many independent organizations instead of a unified body. It is necessary to remember that most conflicts which had inspired rebels and conservatives to form factions were based at the work unit level, and regarded long-standing tensions between those enfranchised by political power and those not (Wang, 1995: 109).

Regardless of their structure however, the proliferation of rebel groups and the disintegration of Wuhan’s central authority left a massive power vacuum in the city, which Mao responded to by calling for “power seizure,” in which the newly established revolutionary forces would re-form for themselves the now devastated political hierarchy. While the rebel organizations leaped at this opportunity to satisfy central demands and form Mao’s “revolutionary great alliance,” soon infighting amongst the groups squandered any possibility of unified coordination and plunged the city further into turmoil (Wang, 2006: 244). Seeing the necessity of restoring some semblance of central authority, Mao’s response was to order the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) of the Wuhan Military Region (WMR), commanded by Chen Zaidao, to intervene on the side of the “leftists.” The WMR forces defined “leftists” as those who were closest to the party line, and thus shifted the balance of power in Wuhan in favor of the conservative factions. The PLA set about targeting and disassembling the lead rebel organization – the Workers’ Headquarters – by arresting their leadership on March 17, imprisoning a total of 485 members. A public statement was then issued a few days later denouncing the Workers’ Headquarters, causing the rebels in Wuhan to completely collapse by the end of March. This subsequently revived the conservatives’ efforts to assert their authority, and the Red Armed Guards – composed of the original Red Guard groups – grew from 50,000 members in January to 200,000 by the end of March, further strengthening the conservative’s hold on the city. Realizing that the military had fallen onto the side of the conservatives and was actively restoring the pre-Cultural Revolution social order, on April 6th Mao had the Central Military Commission issue a Ten-Point Ordinance (Wang, 2006: 245). This command forbade the army from declaring mass organizations “reactionary,” disbanding them, retaliating against those who had assaulted soldiers, and to make arrests without unquestionably clear evidence – severely curtailing the WMR’s ability to confront the rebels (Wang, 2006: 245). In response all the preexisting rebel organizations, sans the destroyed Workers’ Headquarters, resumed their activities. This re-emergence prompted the now far-more organized conservatives to begin coalescing into a loose but unified organization called the “Million Heroes.” This began with the creation of a liaison center on May 16th, which, as conflicts escalated between conservatives and rebels in the following weeks, was restructured into a formal organization on June 3rd. This unification of the fifty-three conservative factions brought together some 1 million members underneath a single central headquarters with ten sub-headquarters which each managed activities in an administrative district of the city. The rebels similarly attempted to create a more unified organization, drawing together the student-based Revolutionary Rebel Students of Wuhan (founded May 6) with the United Headquarters of the Revolutionary Rebel Workers of Wuhan (founded May 8) to create the United Headquarters of the Wuhan Revolutionary Rebels on June 1st. Tensions rose between these groups and the military surrounding the issue of whether the Workers’ Headquarters should be rehabilitated, with the conservatives supporting the military against the rebels. Following a violent confrontation between conservatives and rebels on April 29th, the city’s factions escalated into violence. Rebels claimed that between April 29th and the end of June there were a total of 174 violent confrontations involving some 70,000 people and resulting in 158 deaths and 1,060 injuries (Wang, 2006: 248). While the rebels described such conflicts as originating with the conservatives, the WMR held the rebels responsible for 342 attacks on PLA soldiers resulting in 226 wounded and 38 severely injured between January 6 and June 30th. The Third Headquarters, a more moderate group between the two sides, described 107 incidents of violence, only 6 of which were instigated by the Million Heroes (Wang, 2006: 248). As the violence escalated it drew the attention of Beijing, which insisted Chen intervene. However, the Ten-Point Ordinance left the PLA with few options, and it was only on June 26th, after Beijing offered to host a meeting between faction leadership, that peace returned to the city. The situation would remain tense but peaceful from June 27th through July 15th as both sides avoided confrontations which might present them in a bad light at the negotiating table.