New Concessions and New Industries

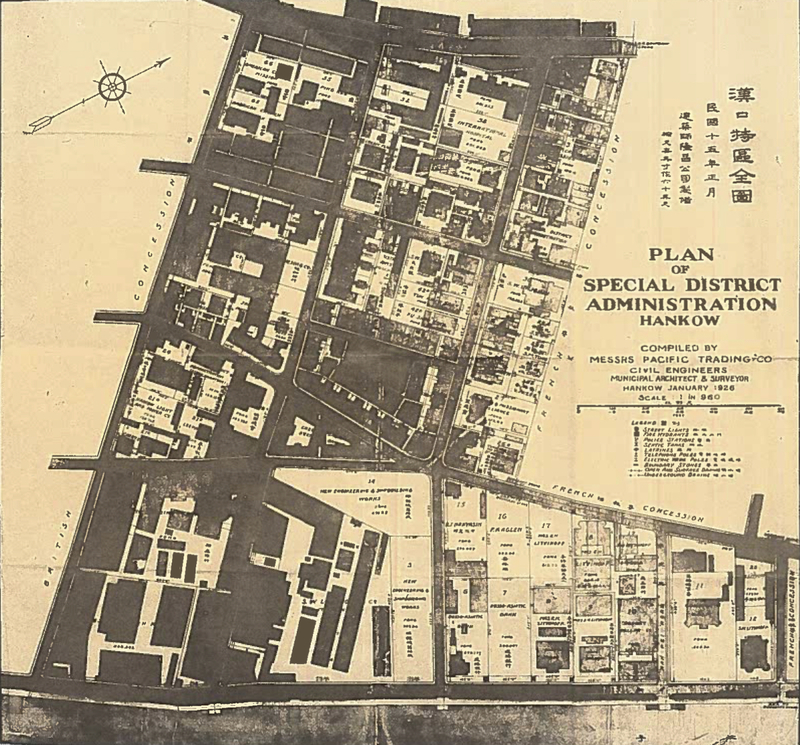

In 1895, the Treaty of Shimonoseki brought the first Sino-Japanese War to a close and granted significant concessions to the Japanese victors, signifying to European powers the Qing dynasty’s inability to protect itself against further unequal treaties. In the following years, Germany, Russia, France, and Japan would leverage this weakness to attain new concessions in Hankou, extending together up the Yangtze in a unified block of foreign territory. While these spaces were generally international in terms of foreign mobility, capacity to rent property, and to some extent shared governance under the Municipal Council, the attachment of nation-states and their nationals to asserting boundaries, articulating authority, and creating symbols of power and grandeur also shaped the concessions and the way people moved within them. This section will explore the details of each concession with a focus on space over temporality, examining the narratives behind their creation and attempting to allow the viewer to step into each space temporarily. The Treaty of Shimonoseki also legalized foreign factory ownership and operation in China, paving the way for the development of new industries in Hankou which would spur growth and further increase friction between the city’s Chinese and foreign inhabitants. Furthermore, during this period the British (and other) concessions’ strict rules on Chinese movement, rental and ownership of land, and operation of businesses within the concessions began to slacken. By 1908 the areas of the concessions closest to the bund and the Yangtze were principally occupied by their associated nationals and other Westerners, while the streets furthest inland, at the “backs” of the concessions housed Chinese and Japanese firms (excluding the Japanese concession), factories, and warehouses (Wright, 1908).

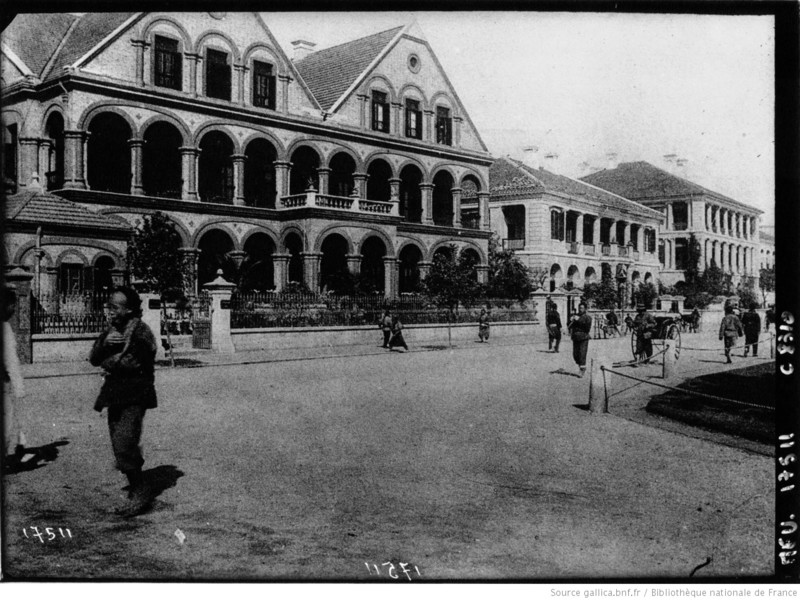

German Concession:

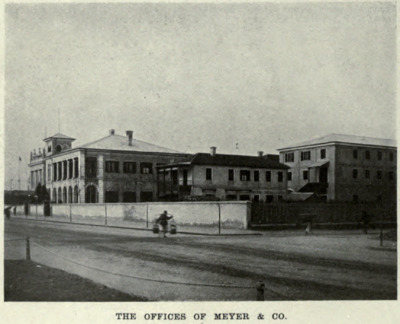

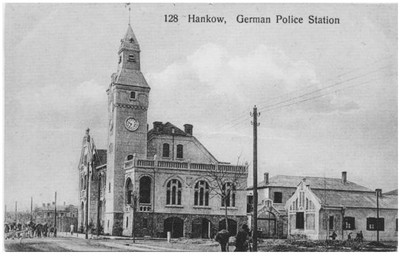

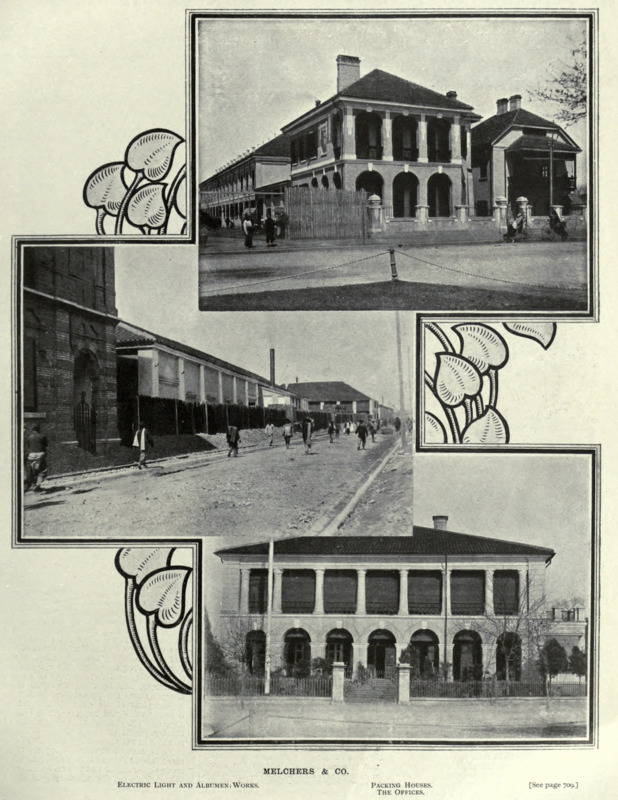

In October of 1895, Germany was the first foreign power to negotiate for a concession in Hankou, with a German company obtaining a 420,000-square-meter area outside of the city wall to the north of (but not adjacent to) the British Concession (Neild, 2015: 103). Despite these early plans actual construction went slowly, and it was not until the 30th of May 1899 that the first foundation stone was laid for the German bund by Kaiser Wilhelm’s brother, Prince Heinrich. The bund was completed in 1903, and by 1905 the concessions’ roads had been laid out – fittingly unaligned with the streets of the French Concession to the south. In 1906 a municipal council was established for the management of the settlement constituted of the concession’s various landowners. Many of the German firms in Hankou operated in the business of producing low-end products such as tallow, wax, pig bristles, and hides, odorous processes which at times motivated the distain of other concession residents. Some of these companies, like Meyer & Co. and Melcher & Co. were already active in the city with compounds in the British concession, and moved their headquarters and facilities into the German Concession. These companies, like many others, operated out of large, ornamental buildings for office staff and management, arranged nearby and often in front of their godowns and drying yards. The German hide company Melcher & Co. built a power station in 1907 which provided electricity to the German concession and the Japanese one to the north, and after the completion of the Beijing-Hankou railway a spur line was added to the concession to improve its industrial capacity. Possibly due to the smell of tallow and hide production, the majority of Hankou’s 300-strong German population actually lived in the French concession, with only around one third settling in the concession. Still the German community united on several grounds, such as the municipal council building and in their own social club. In 1906 a row of lihong houses (similar to those found in Shanghai) were constructed for Chinese residents at the western edge of the concession, demonstrating to some extent the blurring of lines between foreign and Chinese spaces (Neild, 2015: 103).

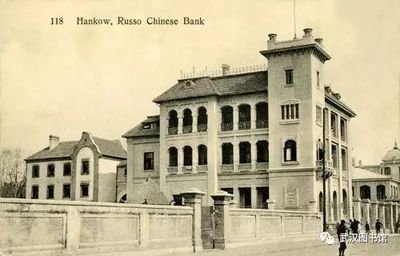

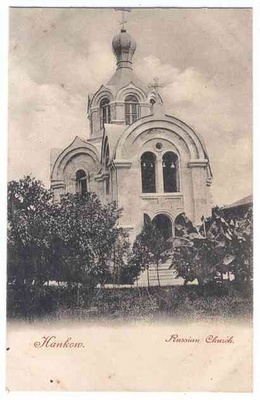

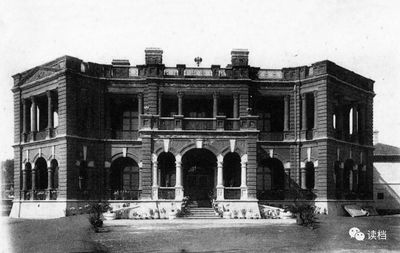

Russian Concession:

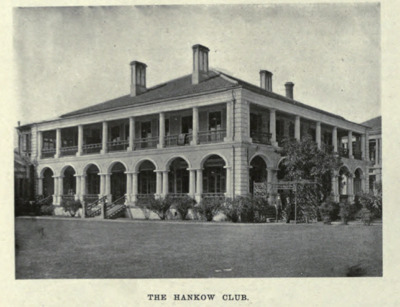

The Russian inhabitants of Hankou had long struggled with British control over the shipping industry on the Yangtze. Despite being responsible for over 85% of tea leave exports in 1894, Russian businesses controlled a much, much smaller share of shipping compared to British firms, meaning Russian exports had to negotiate with British companies for access to much more efficient and timely oversea trade routes (Eiermann, 2005: 41). Local merchants and the Russian Consul Aleksandr Stepanovich Vakhovich, seeing other countries vying for concessions in Hankou following the treaty and confident of potential economic gains, petitioned Count Artur Pavlovich Kassini, the Russian minister in Beijing, in September of 1895 to advocate for the creation of a Russian concession (Crawford, 2018: 979). Kassini selected an area of 276,000 square meters to the north and west of the British concession which many Russians already inhabited, and sought the support of Sergei Witte, the Russian minister of finance and the most influential voice in the Russian court on East Asian policy. The Russian political establishment saw the creation of a Russian concession as a means to further national prestige vis-a-vis Great Britain while promoting a uniquely Russian form of imperialism which was more adaptive and amiable towards native populations (Crawford, 2018: 971). Witte, amongst others, viewed Hankou as a vital site for its position in China’s future rail network, when it would be connected to Beijing and, by extension, the Trans-Siberian railway, solidifying Witte’s vision of a powerful national economy to protect Russian sovereignty and culture (Crawford, 2018: 983). The process of surveying the land was started in December of 1895, but the concession was not officially created until April 14th 1896 due to difficulties evicting Chinese tenants (as planners sought to demonstrate the superiority of Russian imperialism and refused to evict) and several British firms which were expropriated, causing lasting disputes (Crawford, 2018: 984). In 1903 the Russian Consul A.N. Ostroverkhow turned over day-to-day management of the concession to a municipal council, and by 1908 had largely withdrawn from governing and instead presided over a weekly Mixed Court for the concession (Wright, 1908: 699). While the tea factories constructed before the establishment of the concession stayed in the British concession, many company headquarters moved into the Russian concession, along with Russian nationals who built houses there. The Hankow Light & Power Co., based in the Russian concession, provided power to the Russian concession and by 1906 the British and French concessions as well. Formed soon after the establishment of the concession around 1898, the Russian Club formed the Hankou Club’s counterpart for the sizable Russian community, providing a meeting space and a site for recreation with a bowling alley and tennis courts.

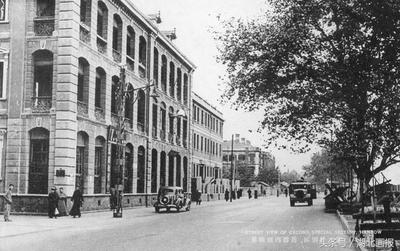

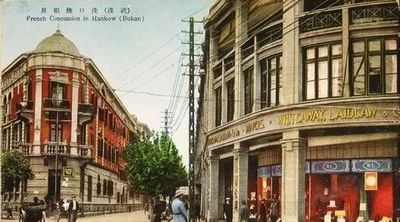

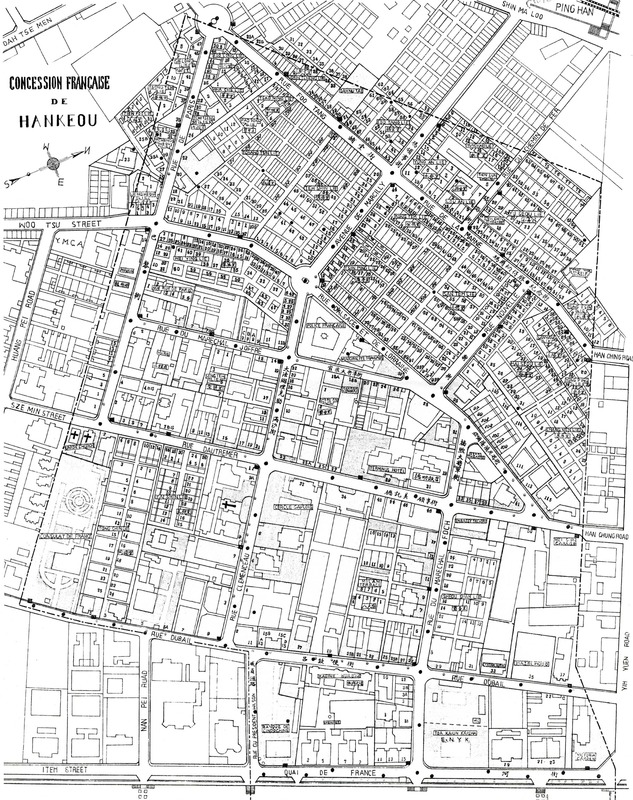

French Concession:

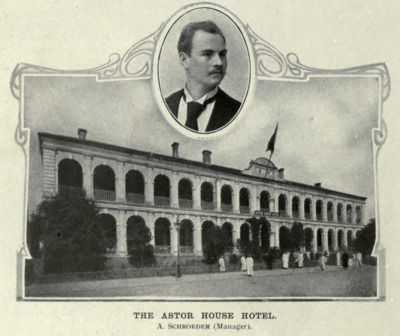

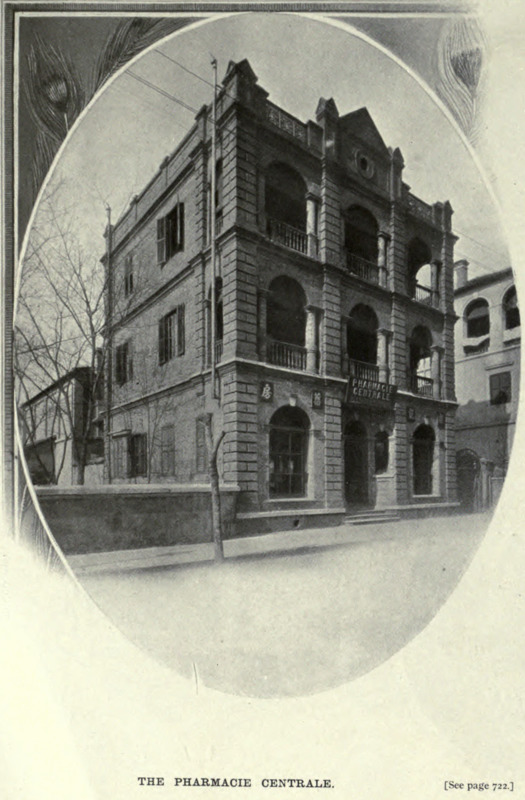

While plans for a French concession in Hankou had gone back to the establishment of the British one, in June of 1896 the French government officially leased the 125,000 square meters remaining between the Russian concession and the city wall (Neild, 2015: 104). In 1902 the concession was extended by 50 percent, bringing it further inland nearly up to the railway line. The French consulate which was constructed in 1865 was already located in the area on the grounds of the British racetrack (which was taken down and rebuilt in a location further north of the concessions), and a larger consulate and residence was completed in the heart of the concession during the 1880s (Neild, 2015: 105). A small municipal council was formed in 1898 and managed the concession under the leadership of the French Consul. While the concession was initially slow to grow it developed into one of the most densely populated, in 1908 housing 56 French nationals, 186 other foreigners, 154 Japanese and 1,500 Chinese. Thus the French concession was one of Hankou’s largest residential areas for foreigners and wealthy Chinese. Wide, well-kept boulevards intersected at distinct angles following the bends of the wall which was demolished in 1908, giving the concession a unique spatial layout. Those disembarking at the Dazhimen railway station (the primary stop for the concessions) to the north of the concession would make their way through these streets to one of Hankou’s three hotels, the Hankow, the Astor House, and the Terminus – all located in the French concession. These establishments ranged in amenities, the Astor House being the most luxurious, and made the French concession into the center for Hankou’s visiting foreigners. The French concession was further home to a French Club, the Cercle Gaulois established in 1899, and accompanied, briefly in the 1900s by a Cercle Belge (Neild, 2015: 113). There was also a flour mill, several factories, and a number of public buildings including a post office.

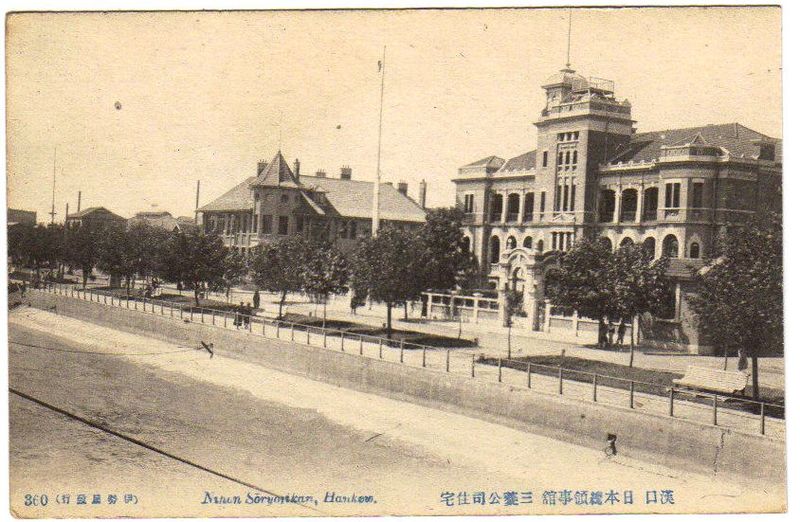

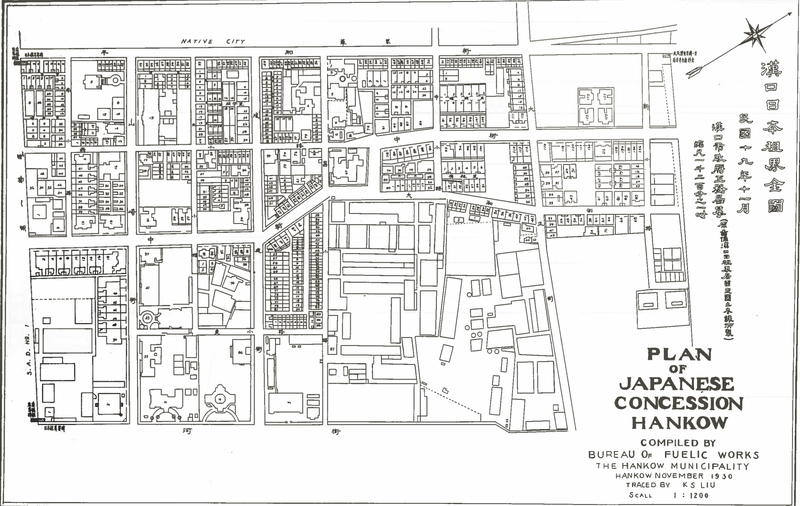

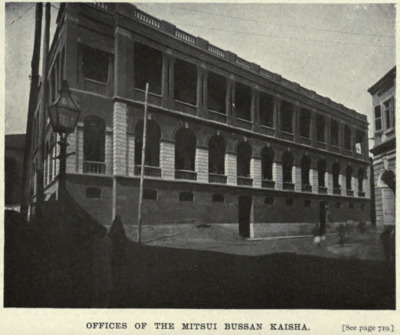

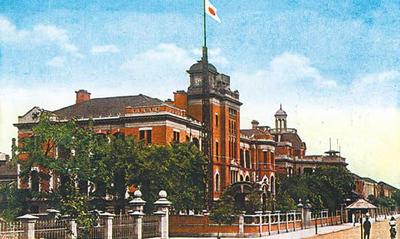

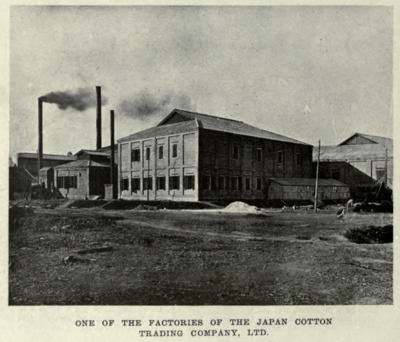

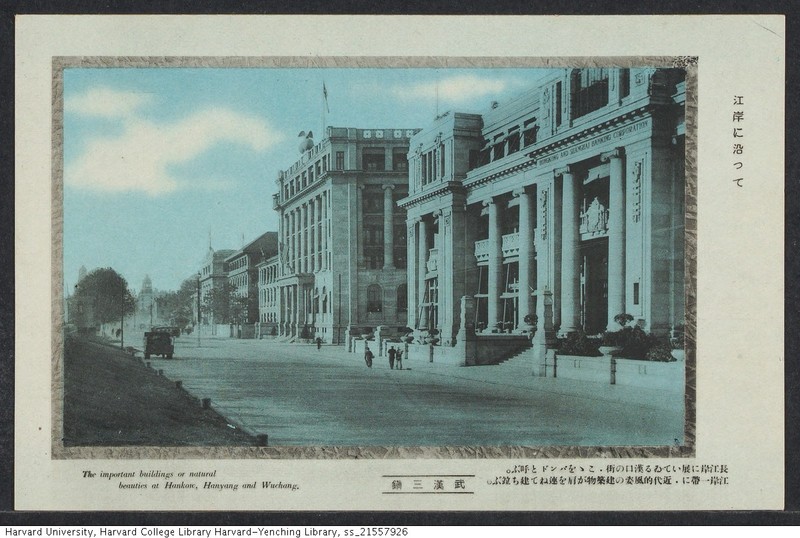

Japanese Concession:

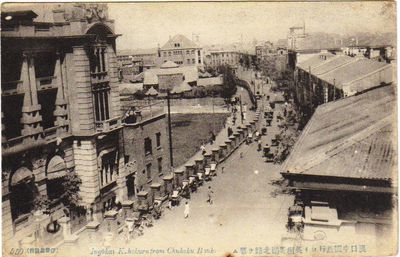

While the Treaty of Shimonoseki opened the way for further European exploitation of Qing weakness, it was not until 1898 that Japan sought to establish a concession in Hankou. A 123,000 square meter plot was selected to the north of the German concession, an area which was extended in 1902 to around 300,000 square meters. Prior to the establishment of the concession many Japanese firms had already established themselves at sites in both the native city and the other concessions, including several large factories and trading firms (Wright, 1908: 720). These companies and independent merchants continued to prosper after the establishment of the concession, and business grew rapidly despite the recent war. By 1907 however Japanese businesses had been joined with Westerners as the subject of anti-imperialist sentiments, and Japanese industries continued to face competition with more cohesive Western businesses (Neild, 2015: 106). The Japanese concession became a major center for industry amongst the concessions and for Chinese entrepreneurs avoiding discrimination, housing the Japan Cotton Trading Co. and the Sui Hua Match Factory, founded 1904 and 1908 respectively (Neild, 2015, 110. Wright, 1908: 719). The Japanese concession was also known as a center for criminal activity during this period, being a distribution point for opium, heroin, and other drugs (Niu, 2017: 32). The concession’s association with drug runners and arms smugglers gave rise to the phrase “下东洋租界去啊” or “going down to the Japanese concession,” as a euphemism for going to do illegal activity. Despite its ugly side the designers of the Japanese concession sought to place it on par with its European neighbors in terms of architecture and spatial aesthetics. The completion of the Japanese bund, for instance, brought the plane tree-lined boulevard over four-kilometers from the British Concession, the longest in China (Neild, 215: 106).

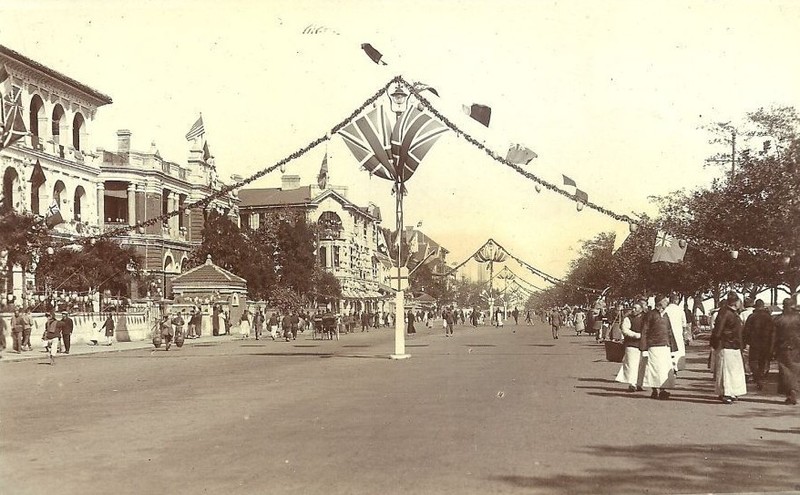

The British Extension and the 20th Century British Concession:

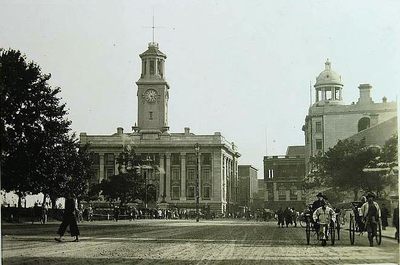

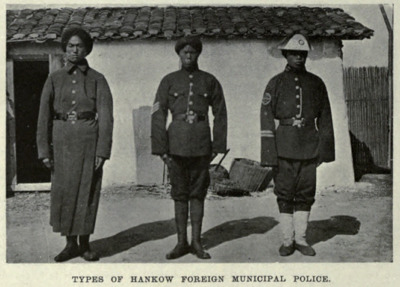

The establishment of the sizable German, Russian, and French concessions, all larger than the British concession in 1896, called in to question British prestige as the dominant economic, political, and military power in Hankou. In 1898 plans were drawn up for a westward extension of the concession by an additional 226,000 square meters, raising the its size to 469,000 and thus surpassing the previously largest German concession. The drying of hides, a popular but odorous industry in Hankou, was permitted in this new area, and “’under certain rules and regulations, it is proposed to allow respectable Chinese’ to live there as well” (Neild, 2015: 106). Following this extension and the economic revival experienced in Hankou’s foreign-operated industries between the 1890s and 1930s, many new structures rose in the British concession – alongside of and replacing older trading hongs. The most visually prominent of these new buildings housed the British concession’s premier banks, including the Shanghai and Hongkong Bank, the Yokohama Specie Bank, and the Chartered Bank. The British consulate, already considered lavish by the standards of the time in the 1860s, had been rebuilt in 1882 and many additional buildings were added during the 1910s and 20s. The British bund, lined with plane trees that now shaded over the wide street and grassy area adjacent to the water, was patrolled by a mixed police force with British, Sikh, and Chinese constables.

Beyond and Between the Concessions:

The Beijing-Hankou railway brought changes to the foreign concessions prior to and long after its completion. The company of Belgian designers and engineers hired to construct the railway was granted a portion of land to the north of the Japanese concession to live on as well as house various supplies and machinery (Neild, 2015: 106). 64 Belgian railway engineers were settled there along with a team of 24 mostly Belgian engineers hired by the Hanyang Ironworks and Arsenal. In the years which followed the railway’s completion in 1906 the Belgian residents pursued turning the area into a Belgian concession, however this claim was eventually repudiated in 1908. The completion of the railroad brought improved export capacity for Hankou-produced goods and increased connectivity from Hankou’s isolated inland location with the major political hub of Beijing and the large foreign settlements in Tianjin. Foreign companies, enterprises, and individuals extended their reach elsewhere in Wuhan as well. A significant portion of land was purchased or leased in the area further north of the Japanese concession, on which sat several oil storage facilities for Hankou’s river traffic and industry. Furthermore, in 1900 a general foreign concession was opened in Wuchang on the opposite side of the Yangtze by Zhang Zhidong, who permitted foreign residences and offices under similar restrictions offered to the Chinese residents of the Hankou concessions. Boundaries between national and international were never quite fixed in the Hankou concessions. Despite each falling under a flag with a municipal council, a police force, and certain national social circles, they also shared an incredible deal in common. A significant portion of the foreign population lived in concessions not associated with their nationality, and despite a degree of competition the distinct governments of the settlements were generally cooperative. A 1908 guide to Chinese treaty ports described Hankou’s governmental staffs as “larger than would be necessary under a more reasonable and business-like arrangement,” and it was potentially the degree of localized autonomy and equally swelling-pockets amongst officials that encouraged such cohesion (Wright, 1908: 693). Hankou’s foreign residents moved freely between the various concessions, reading the same two daily newspapers – The Hankou Daily News and The Hankou Mail – and socializing together at the stately Hankou Club and racetrack. An organized and modern system of fire brigades would protect the city during the 1911 fires which devastated the neighboring native city, and in the turbulent decades to come different concessions’ police forces often came to the aid of others. The military forces of the various foreign nations would also come to each-others’ aid, and the Hankou Volunteers – an armed regiment of mostly British locals – was also tasked with defending the concessions from the conflicts which frequently swirled beyond its confines. By 1912 the population of the concession had grown to some 1350 Europeans and Americans, over 1500 Japanese and almost 28,000 Chinese residents, and Hankou’s trade was booming – its customs revenue having grown to be the second largest in China (Neild, 2015: 112). Despite this all however it is important to remember the persistence of tensions. British merchants and Russian officials clashed for years over the British properties which had suddenly been transformed into the Russian concession, and according to one story after it was announced the French had received a concession, a number of British nationals descended on the site and ripped up the stakes (Fraser, 1999: 156). Tensions between the foreigners however paled in comparison to the growing animosity between Chinese residents and those who inhabited the concessions. On the 23 of January 1911 a supposedly ill coolie was taken by police into the municipal council building. After it was revealed that he had died it was claimed by other coolies that he had been kicked to death by police (Neild, 2015: 111). An ensuing mob of 3000-4000 moved on the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank as an expression of outrage against unfair loans issued to the Qing government for railway construction. The rioters overwhelmed concession police and the foreign volunteer corps, being repulsed by troops aboard British and German gunboats lying in the river. Another mob which had formed on the opposite end of the British concession was also met with physical force, when a British officer ordered a bayonet charge which left 30 to 40 Chinese dead. The situation was only resolved with the arrival of 3000 Chinese troops sent to maintain order. As anti-imperialist sentiments grew in China such incidents would become more and more prevalent, and in Hankou would end with the return of the majority of the concessions by 1927.