There is No Contradiction Between Socialism and a Market Economy

The death of Mao Zedong in 1976 and the beginning of the reform and opening period which followed marked a turning point of Wuhan and for China as a whole. The heart of Wuhan’s economy for the majority of the socialist period was heavy industry, although a substantial light industry sector had also developed focusing on textiles and food processing amongst other products (Solinger, 1993: 84). When the central government began implementing economic reforms in the early 1980s, there was a shift in funding and focus away from heavy industrial state-owned enterprises (SOEs) like Wuhan Steel and Iron and the First Metallurgical Corporation. As the center’s interest rotated towards light industry and agriculture, machinery enterprises faced severe cutbacks and were forced to handle newly emerging competition with other production centers in China. Wuhan’s textile industry, on the other hand, benefited in the early 1980s from new state investments, and Wuhan’s established position as a major textile center helped it weather the reforms which exposed these traditionally protected companies to new markets. Overall however, the predominant shift in the 1980s directed the center’s attention away from urban industries and towards companies and districts outside of China’s megacities (Taylor and Xie, 2000: 145). As the interests of both central and Hubei provincial governments changed to target investments towards regions outside of Wuhan, the city suffered an economic downturn and it was left to the city-level government to try and improve growth. City officials were innovative however, and in the 1980s Wuhan became one of the first cities in China to introduce stock-sharing, leasing and bidding. By 1988 the city had introduced a revolutionary system of enterprise mergers, followed in 1992 with a unique system through which foreign investors could purchase enterprises at reduced rates in exchange for introducing modern management systems (Taylor and Xie, 2000: 146). By the 1990s Wuhan’s economy was growing considerably again as investment streamed in from abroad (Pong, 2009: 103). The Wuhan city government’s creation of a number of developmental & industrial urban districts – including the Wuhan Economic and Technology Development District, Donghu New Technology District, and Wujiashan Taiwan Investement District – has assisted in this process. A large portion of this foreign capital has arrived from France, with one third of France’s investment in China being directed into these districts alone, a situation potentially derived from France’s long colonial history in the city (Pong, 2009: 103). The Donghu New Technology District – founded in October 1988 – has become internationally famous as the “Optics Valley of China,” and hosts some 42 universities, 22 state key laboratories, 24 national engineering technology centers, and 56 national scientific research institutes (Hubei Provincial Government, 2013).

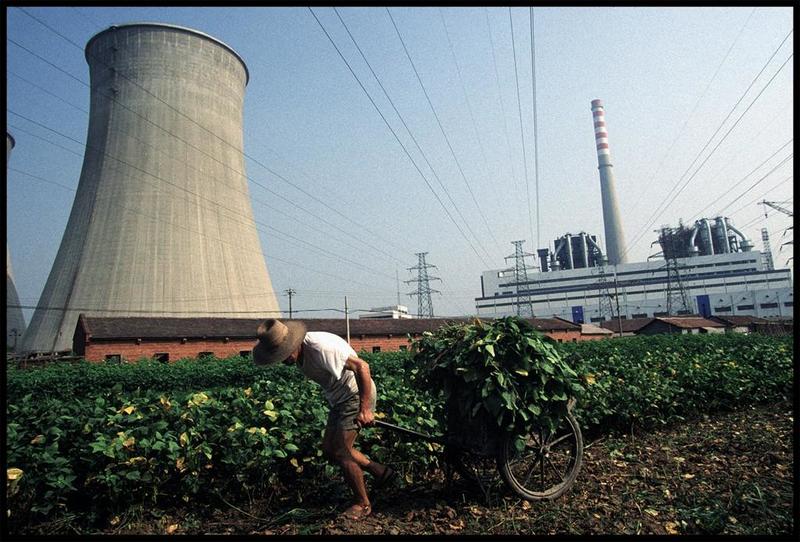

While the city’s government prides itself on Wuhan’s contributions to China’s developing high-tech sector, Wuhan’s history as a center for heavy industry has far from faded. Wuhan Iron and Steel, the same company established in 1955 as part of the First Five-Year Plan, was merged with the Baoshan Iron and Steel group in 2011 to form Baowu Steel Group – the second largest steel maker in the world (Lin and Stanway, 2011). Despite the advantages this industrial giant has brought to Wuhan, scientists have also observed the lasting impact of Wuhan’s industry on its local environment. A 2000 study described the city’s environment as “seriously degraded,” facing high concentrations of sulphur dioxide, nitrogen oxides and dustfall levels (Taylor and Xie, 2000: 157). Surface water sources are also highly polluted, the product of hundreds of years of poor water management and industrial waste incidents. Despite efforts by local government officials to address the persistence of these issues, the city still ranks from high to very high in measures of air and drinking water pollution (Numbero, 2019).