Industry under the CCP

A New Steel Industry

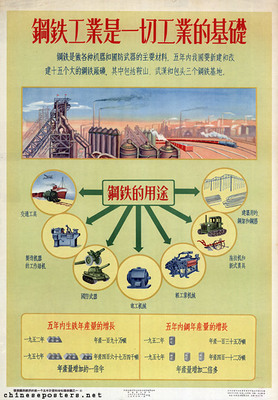

In May of 1949, former GMD officer Zhang Zhen led Wuhan’s workers in a revolt against the post-war Nationalist government in Wuhan, paving the way for the arrival of the People’s Liberation Army from the north (Zhou, 2011). Despite this relative peaceful transition of power, Wuhan was still a shell of its former self following the Second World War, with its factories having been destroyed or disassembled following the Nationalists’ retreat. The Hanyang Ironworks, the former basis of Wuhan’s heavy industry, had been almost entirely transported to Chongqing, and ended operations in July 1947 as demand for steel declined following the war. Despite its now complete lack of a native heavy industrial component, Wuhan was favored by the new Communist Government for a number of reasons, all based around its geographic location. Wuhan was already at the center of a rail and water way hub, useful for transferring in raw materials and exporting finished steel, and it was close to Daye, some of Central China’s most productive iron mines (Chang, 1970: 277). The combination of abundant and nearby natural resources and the city’s strategic, defensible inland location led Mao, much like Zhang Zhidong over fifty years earlier, to declare on March 15, 1952 that “Wu-han shall be the nation’s second steel base.” These words secured Wuhan’s place amongst the “key cities” for socialist development in the First Five-Year Plan (1953-1957), which would once again transform it from a devastated warzone to a thriving factory town (Pong, 2009: 102). Following Mao’s decision enormous efforts were set underway to transform Wuhan into a new industrial base. Surveyors were sent out by the Ministry of Geography to examine further sites for or extraction, while sites were selected for the new facilities on 30 square kilometers of swampy land to the south of Wuchang (Chang, 1970: 277). While blueprints for the project were drawn with Soviet technical aid, the new Wuhan steel industry was unique in its reliance on nationally-made parts. In the construction phase between 1955-1957, workers were drawn by the thousands from steel plants all across China’s northeast, and about half the plant’s equipment and materials were domestically produced.

The "Great Leap Forward"

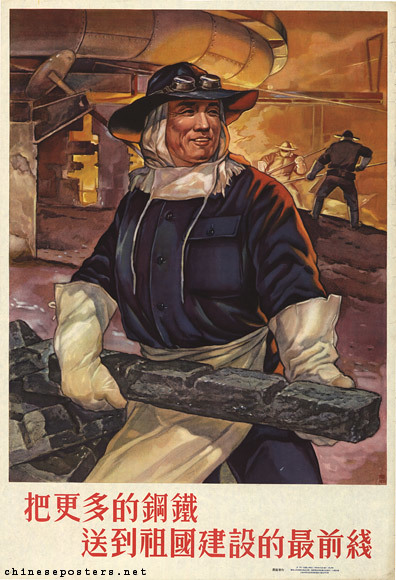

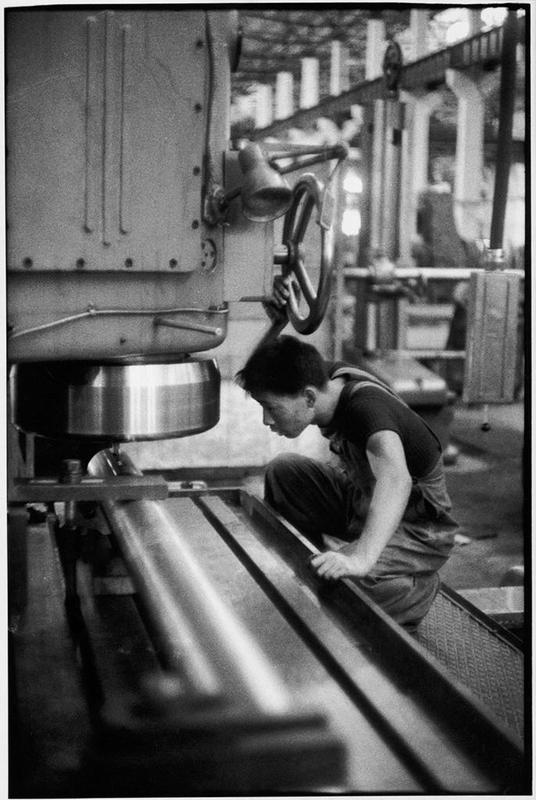

A Chinese metal worker examines his machine in one of Wuhan's steel factories, 1958.

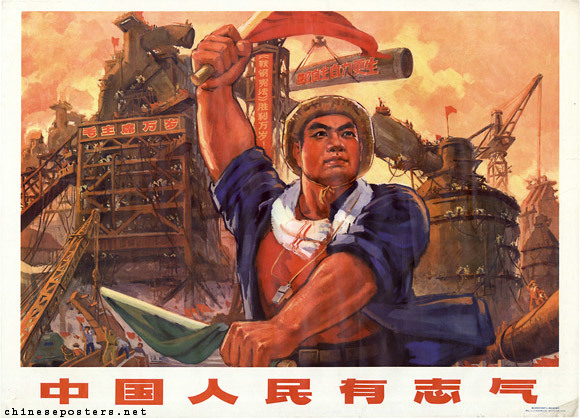

As the facilities at Wuhan had been designed and built from scratch without any major pre-existing infrastructure, they were able to attain a level of modern efficiency rarely seen in China’s other steel producing districts. By 1959 Wuhan’s new industrial sector was employing nearly 100,000 workers, and by 1970 it was nearly surpassing the country’s lead steel producing facility in An-Shan. As the steel produced in Wuhan was already enough to meet local needs, the plants’ distribution of the excess throughout Central and South China provided a massive economic stimulus. Wuhan’s new steel sector further provided intensive training programs for workers in other provinces, offering the Baodou steel plant with more than 6,000 skilled workers and 1,700 technicians and cadres. The advantages of the new steel factories expanded beyond Wuchang, leading to the development of a number of other industries in manufacturing electrical equipment, textiles, lathes, chemical, metals, and machine tools. Companies like the Wuhan Dockyard, the Heavy Machine Factory, and the Thermoelectric House would grow Wuhan’s working population from 124,000 personnel in 1950 to 844,000 in 1960. All of these factors – the development of the Wuhan industry from scratch with nationally-sourced parts, the enormous population of workers contributing towards China’s proletarian future, and the sharing of technical knowledge across China and developing nations – would translate into powerful propaganda perpetuated and reinforced by the CCP’s ideology. Workers in Wuhan, like many other places in urban China, began to define themselves by their levels of productivity, and their contributions to state advancement. While those who excelled were promoted up the party structure, those who failed to meet quotas were labeled as “backwards elements (Wang, 1995: 34). Tensions between these groups would erupt during the 1960s as part of the Cultural Revolution in Wuhan.

The Yangtze River Bridge

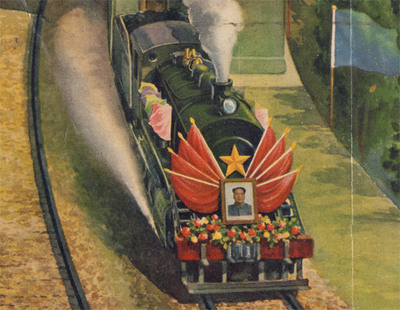

Prestige and utility went hand in hand in the CCP’s approach to industrial projects in Wuhan. With the First Five Year Plan that reinvigorated Wuhan’s industry came an infrastructure project to demonstrate the power of China’s new government to overcome traditionally insurmountable odds: the First Yangtze River Bridge. The Yangtze had long imposed a significant barrier to travel between the tri-cities, with Wuchang – the educational, cultural, political, and now industrial capital of the city being separated by the river from Hankou and Hanyang. Traditionally, all people and goods, from train cars to tanks, had to travel by ferry across the river before they could continue their journey south on the Hankou-Canton railway. A permanent bridge built across the Yangtze would solve this problem, and would further represent an impressive feat of engineering due to the Yangtze’s frequent and tumultuous floods. Plans for the Wuhan Yangtze bridge began in the spring of 1950, and in April 1953 the Ministry of Railways created the Wuhan Bridge Engineering Bureau to design and carry out the project (Yu, 2007: 32). A site was selected at the base of Turtle Hill in Hanyang, where the bridge would stretch across the river 1,670 meters to the opposite shore in Wuchang.

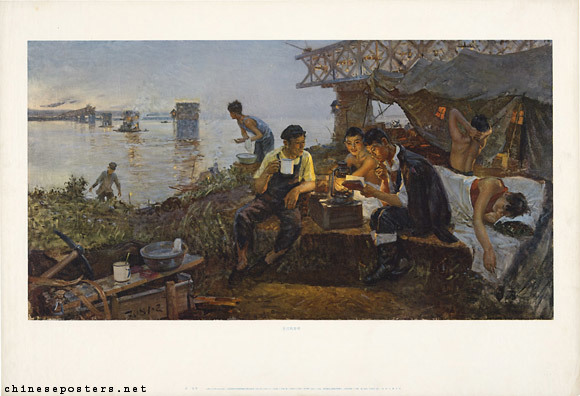

Construction began in September 1955, and when the bridge was opened for traffic on October 15th 1957 it was heralded as a triumph of modern Chinese engineering, and became a widely accepted symbol of national pride. Several posters commemorating the bridge’s opening capture a unifying grandeur as the bridge extends almost infinitely into the distance, dwarfing the flags and celebrating people walking beneath it. Others commemorate the bridge’s workers, furthering the state’s ideology tying proletarian work-ethic to national triumph. While the bridge was still under construction, Mao referenced it in one of his poems:

Sails move with the wind.

Tortoise and Snake are still

Great plans are afoot:

A bridge will fly to span the north and south

Turning a deep chasm into a thoroughfare

The significance of the Yangtze bridge’s creation to the Communist narrative of national unity founded through hard labor and dedication cannot be understated, but its meaning for Wuhan many have been even greater. By bringing together the two sides of the river with a passage that could be walked, driven on, or ridden over by train, the Yangtze river bridge united Wuhan physically for the first time in its history. Although the following decades of the Cultural Revolution would soon sour the proletarian spirit which had been built up in Wuhan during the 1950s – slowing production as a result of constant infighting – true change in Wuhan’s industrial sector would come not at the hands of factions but with the market reforms of the 1980s.