Refuge and Isolation

The tensions leading up to and ultimately resulting in the 1937 Second Sino-Japanese War and, later, the Second World War, would prove to be an entirely new force in shaping concessionary dynamics. The first of these incidents came on September 21st 1936, when the death of a Japanese consular policeman inside the Japanese concession prompted a force of two destroyers and a large contingent of marines to be sent to Hankou from Shanghai (Neild, 2015: 116). They joined the five warships and 300 marines already stationed in Hankou, igniting fears in the Chinese city and the concessions alike until they were ordered away later that month. After all-out war was declared in July 1937, on the 16th 3000 Chinese troops surrounded the Japanese concession and squared off with Japanese marines, though nothing came of this confrontation at first. By August all Japanese civilians had left for Shanghai, followed by the Japanese Consul, leaving the concession largely empty, with businesses closed except for spaces still inhabited by various Japanese military personnel. By the 11th of August they too would make a hasty retreat, and Japanese bombing of the city – now isolated completely due to the Japanese military’s advances further down the Yangtze – commenced shortly after they had left. On August 13 1938 the Chinese municipal authorities converted the former Japanese concession into Hankou’s 4th Special Administrative District, however this designation would offer little protection from the looting and destruction perpetuated by angry Chinese civilians against this symbol of Japanese imperial aggression (Neild, 2015: 117).

Those foreigners remaining in the city, settled in the sole-remaining French concession and the other Special Administrative Districts, reacted in their own ways to the increasing violence and the impending Japanese advance up the Yangtze. Sixteen Americans and twelve Russians volunteered to fly for the Chinese Air force defending the city against aerial bombardment, attacks which intensified after Wuhan became the Chinese capital on December 1st 1937. Other foreigners fled the city, the British cruiser HMS Capetown taking one man, 21 women and 26 children up the Yangtze 4 days before Christmas and another group of four fled south to Canton via the railroad, dodging Japanese attacks along the way. Many, however, chose to stay in the city and its concessions, mingling in bars and at the racetrack with the foreign correspondents and diplomats that had flooded into China’s wartime capital. During this period the remaining concessions had come to host an enormous number of refugees from Chinese cities along the Yangtze, particularly Nanjing and Shanghai. The population of the French concession had risen from 15,427 at the end of 1936 to 23,133 by the end of 1937, putting pressure on already strained public resources (Rihal, 2016: 224). The Nationalist retreat to Chongqing in June of 1938 signaled further changes, and as Japanese naval forces massed on the Yangtze, the British Ambassador to China advised British Consuls on the 12th of July to not evacuate “unless it is absolutely essential,” fearful of the difficulty of British return if they chose to leave and the destruction of British property which might follow. British residents were advised to hunker down in the Hongkong and Shanghai Bank and Asiatic Petroleum buildings, where they would be defended by Marines and the Navy gunboat stationed in the Yangtze. While an additional 200 Royal Marines were brought in from Hong Kong on August 19th, they made little difference when the Japanese finally captured the city on October 25. At this time the French concession’s population swelled to between 60,000 to 80,000 people as Chinese refugees, fearful of the encroaching Japanese troops, took shelter within the nationally ambiguous zone (Rihal, 2016: 224). The Royal Marines maintained control in SAD No. 3 for six days, however the situation they were presented with was clear, and they surrendered control of the area to Japanese troops afterwards, despite protests from British inhabitants (Neild, 2015: 117). A Japanese census of the foreign population placed 1163 people living in Hankou from 30 different countries. The largest contingent was the British at 279, followed by White Russians, Americans, French, Italians, Germans, and others –including some 236 missionaries, 20 female dancers, and 15 White Russian Musicians. These individuals, stranded in the ambiguous space between their foreign citizenship, an absent Chinese government, and Japanese occupiers, would be forced to cautiously navigate such boundaries in the years to come.

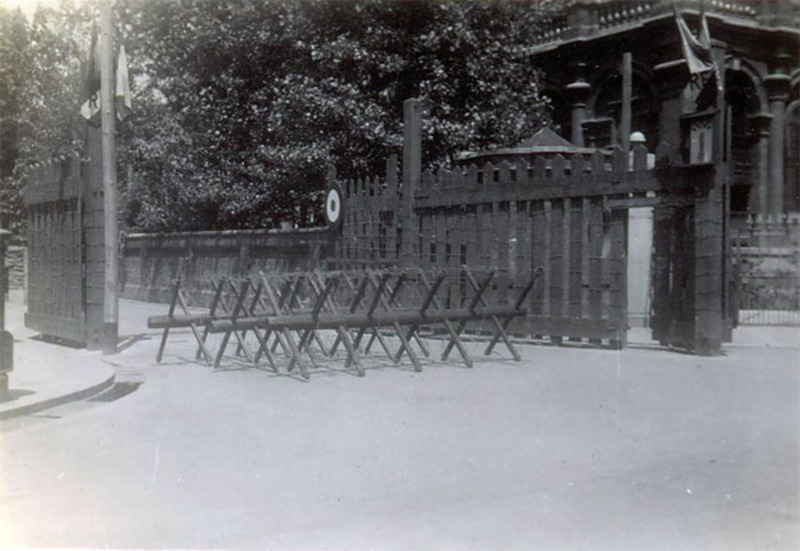

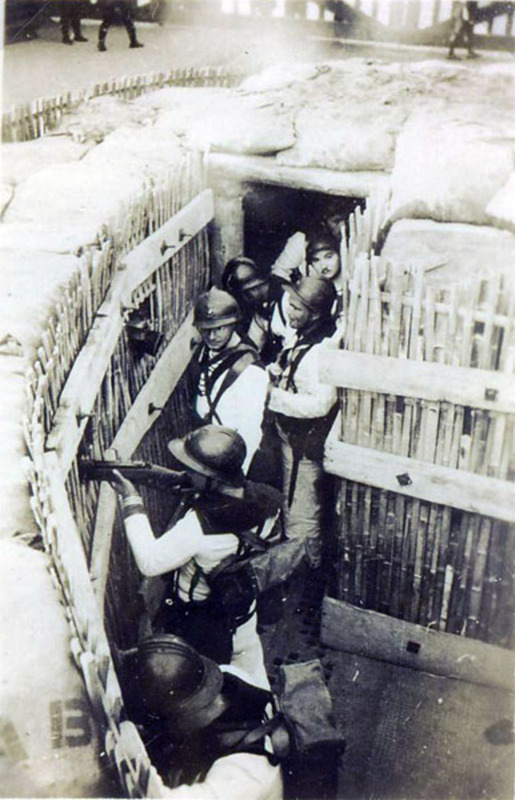

In contrast to the Special Administrative Districts, French authorities maintain control over the French concession, still legally foreign territory, long after the Japanese took the rest of Hankou. France’s ambiguous neutrality towards Japan in the Sino-Chinese and Second World Wars imbued the imaginary boundaries of administrative space which had distinguished the concession area with new qualities, which over the following years would intersect and collide with the real, physical conditions within the concession (Rihal, 2016: 221). The first of these issues faced by French authorities was the flood of refugees into the concession seeking shelter from the violence occuring the Chinese parts of the city. The French concession was officially closed on the 25th of October, 24 hours before the arrival of Japanese troops. Water supplies and telephone lines, based in the Chinese part of the city, were cut off and would remain a serious point of negotiation and contestation. The French began fortifying the concession from potential Japanese intervention and the further inflow of refugees by stationing French and Annamite police at entry points, constructing defensive gates and barricades, and fortifying buildings with barbed wire, machine guns, and sandbags. Despite this, Chinese refugees continued to find ways into the concession, many passing through alleyways and houses to enter and exit (Rihal, 2016: 226). The concession’s growing Chinese population coupled with poor water access and inadequate medical facilities forced the concessionary officials to take matters into their own hands. On November 8th 1938 the “French Concession Hygiene Committee” was established to prevent epidemics and provide free vaccinations, a reaction potentially motivated at least in part by age-old foreign stereotypes of Chinese uncleanliness. A community clinic which provided free examinations and medications was also founded, along with a temporary Franco-Chinese hospital based out of the converted Tiansheng theater. Movement of necessary supplies, particularly water, into the concession was severely limited by the breakdown of administration in the Chinese city and the Japanese desire to pressure concessionary officials into complying with demands. Starting on October 26 water supplies were cut off, and even after pumping was restored in the Chinese city by the Japanese military the French concession remained in short supply, eventually the French Embassy in Shanghai assisted by sending a pump-boat which was used to supply the concession for three months (Rihal, 2015: 231). Electricity, powered by a British plant in the 3rd SAD, was also in short supply and there were frequent blackouts, and food deliveries had to be negotiated across Japanese lines. Even as the refugee crisis began to ease in the later months of 1938, with Chinese residents being allowed by Japanese to relocate to their homes and incentivizing their movement into refugee areas, issues surrounding the movement of people created continuous disturbances. In November 1938, the Japanese authorities began issuing passes to Chinese considered to be ‘good citizens’ which allowed them to move in and out of the concession, providing a vital lifeline to the outside world for those still inside. French officials at first resisted all efforts by the Japanese to establish patrols in the concession, but finally acquiesced to permitting Japanese soldiers to march on the Quai de France (the French portion of the bund) between set hours, though this too often resulted in incidents and friction. The Japanese desire to monitor the concession was largely motivated by its use as a safe haven for Nationalist resistance forces, many of whom worked undercover within institutions like the French police as translators (Rihal, 2016: 233). Japanese attempts to intervene unilaterally in the concession were often met with arrests by French officers, however the two sides also frequently collaborated in cracking down on opium dealing amongst other crimes.

While the establishment of a Chinese puppet regime by Japanese authorities in April 1939 promoted cohesion to some extent, tensions continued to rise as conditions continued to worsen for France in Europe and elsewhere. In April 1939 foreigners were forbidden from exiting Hankou, and in January 1940 French troops disengaged from the city, and over the next few months the civilians of the concession completely disconnected from national French aid. Circumstances escalated when a confrontation between French police and Japanese soldiers occurred on July 7th 1941, resulting in the death of a Japanese soldier and the severe injury of an Annamite policeman. Five Japanese soldiers were arrested, and the concession was immediately closed by officials, resulting in a standoff which ended when the Japanese threated to cut off all access to the concession from the outside. A deal was drawn between the French and Japanese consuls forcing a French apology, the resignation of several officials, and greatly increasing the Japanese control over the French police force and, by proxy, the concession. While the concession’s association with the Vichy government had likely been its saving grace following French capitulation in 1940, it also met Hankou was cut off largely from the outside world, being able to maintain connections only with other French concessions within China and the French administration in Indochina. The years following 1941 were rife with social unrest, as many of the aspects of life concession residents had grown accustomed to fluctuated wildly in their price and attainability. Rents skyrocketed following the influx of new residents in 1937, resulting in some landlords requiring gold ingots as deposits for homes. The currency war between the collaborative government and the Nationalists in Chongqing continued to affect currency prices, and shortages of valuable necessities like water and rice resulted in strikes and demonstrations. Throughout this period the French authorities sought to maintain control by strengthening the police force and reaffirming French nationalism through Vichy propaganda (Rihal, 2016: 235). Despite these efforts, the failure of trade due to the closing of the Yangtze by Japanese forces had completely depleted the concessionary government’s revenue, resulting in desperate attempts to levy new taxes – ranging from opium smokers to dogs (Rihal, 2016: 237). Such fiscal concerns fueled existing fissures in the government, leading key members of the municipal council to resign, leaving only two members by March 1942, and even threatening to divide the police force. While the collaboration between the Vichy regime and the Japanese has postponed retrocession and the abolishment of extraterritoriality, as the 1940s dragged on the position of the concession grew more and more untenable. When treaties between China and the US and Great Britain agreed to the end of extraterritoriality on the 9th and 11th of January 1943, followed by the Japanese retrocession of their concessions on the 14th, France was left with little choice but return its territory to China. On February 23rd 1943, the Vichy government announced the end of the French concessions in China, and a formal treaty was signed with the collaborative government in Nanjing retroceding the Hankou concession. On the 5th of June, 1943 Robert Germain, the French consul in Hankou, officially transferred the administration of the concession to Zhang Renli, the son of Zhang Zhidong and leader of the collaborative government in Wuhan (Rihal, 2016: 238).

The return of the French concession, and its conversion into the fourth Special Administrative District, marked the end of the concessionary period in Hankou. While a number of foreigners stayed in the city for the duration of the war, some even hanging on until the CCP took Hankou in 1949, almost all left before 1950. What was left in Hankou, and elsewhere in Wuhan, were the physical spaces imperialism had left behind, no longer bounded by administrative barriers, nationalities, and the populations which enforced such distinctions. Many of the bund’s buildings have survived till today, leaving civic planners, tourists, and others to manage how these powerful symbols of the city’s history are integrated into its new skyline.