The Incident and its Aftermath

Chen Zaidao was informed by Zhou Enlai on July 10th that the negotiations would occur in Wuhan instead of in Beijing. However, Chen was not informed that Mao Zedong would also be arriving in Wuhan along with the team of representatives from the center. Zhou landed in the city on July 14th to make preparations for Mao’s arrival, and was joined by Xie Fuzhi, Wang Li, and a group of other central military officials assigned to manage Mao’s safety (Wang, 2006: 249). Only Zhou, Xie, and Wang were to be responsible for managing the local situation, and on July 14th Xie and Wang went out at night and in disguise to survey several known rebel headquarters. The two were recognized however, and the following morning the rebels, eager to represent themselves as having the favor of the center, staged massive demonstrations welcoming the “delegation sent by Chairman Mao.” The decision was made by Zhou that Xie and Wang would become the public faces of the center in Wuhan, in order to avoid the public revelation that Mao was in the city and personally managing events. Due in part to this secrecy, the Million Heroes, confused why they had not been informed of the delegation’s arrival and provoked by the rebels’ parading, staged a series of blitz attacks which left 10 rebels dead and 37 seriously wounded. Following the resurgence of violence, Mao ordered his representatives in Zhou, Wang, and Xie to convey to the Wuhan’s only organized center of political power – the WMR – a series of commands. 1) the WMR had made mistakes in its “political line,” and Chen Zaidao and Zhong Hanhua (the Commissar of the WMR) should make public self-criticisms. The basis of this was the mistake of disbanding the Workers’ Headquarters, which should be reinstated as an organization and whose leadership should be released. 2) The city’s remaining rebel organizations were genuine revolutionaries and should become the city’s new leadership. 3) No mass organization should be banned or disbanded. 4) Despite being conservative, this included the Million Heroes, and the rebels should be prevented from taking retribution out upon the Million Heroes. 5) The Third Headquarters was another conservative organization. 6) The WMR should prevent peasants from entering the city to support the conservatives. 7) The WMR should educate its soldiers to support the rebels. 8) All mass organizations must rectify their attitudes towards the PLA (Wang, 2006: 251). When Zhou, Xie, and Wang passed down these instructions down to Chen and the other WMR leadership, they were reluctant to comply, particularly with the self-criticisms, but when it was made clear the orders came from Mao Chen fell into line. Meanwhile, Xie and Wang had been active throughout the city meeting with the Million Heroes and the leading rebel factions. Throughout this process the center’s favoritism towards the rebels was made clear, with Wang in particular praising the rebels while admonishing the Million Heroes for not laying down their arms (Wang, 2006: 253).

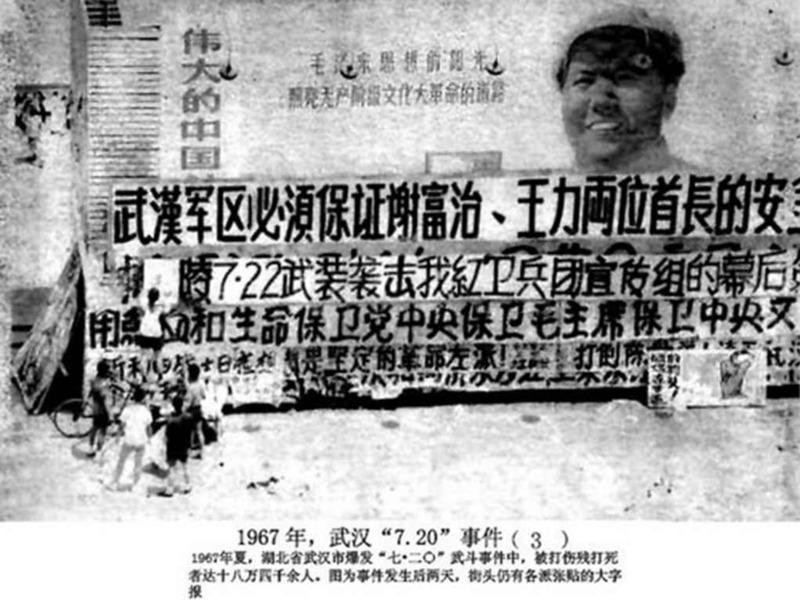

As the rebels spread rumors regarding the center’s validation of their positions, the Million Heroes’ leadership’s concerns were reinforced as the contents of Zhou’s message to the WMR’s top brass was passed on through Unit 8201 – a WMR garrison in Wuhan with close ties to the Heroes. The members of the Million Heroes were outraged at this news and rejected the label of “conservative,” becoming increasingly convinced that Wang, who had been doing most of the talking, was deceiving the central leadership on the part of the rebels. By July 19th fury regarding “Wang’s decision” had reached a tipping point, and it was determined that something had to be done to prevent rebel victory. The Million Heroes were assisted by soldiers from Unit 8201 and 8199, who were sympathetic towards the conservatives and could not understand why the center’s delegation had sided with the rebels the WMR had been working to repress for months (Wang, 2006: 256). On July 20th, soldiers from Unit 8201 and 8199 had gathered at the East Lake Guesthouse where Wang, Xie, and Chen were staying. Because Xie had spoken little during his time in Wuhan he was unharmed, but Chen, at first mistaken for Wang, was beaten with rifle butts, and when Wang was identified he was dragged to the WMR headquarters and beaten badly by the crowd which had gathered along the way. Wang was only rescued when Mao ordered WMR leaders to secure him and move him to a safe place. While this was occurring a series of rumors supporting the Million Heroes had swept through the city, strengthening the morale of the conservatives. They gathered in the streets by the tens of thousands, armed with spears, knives, and clubs, marching or riding on trucks all while chanting “Wang Li get out of the CRSG” and “Wang Li get out of Wuhan.” They were joined by members of Units 8201 and 8199, who armed with rifles swept through the city targeting rebel strongholds.

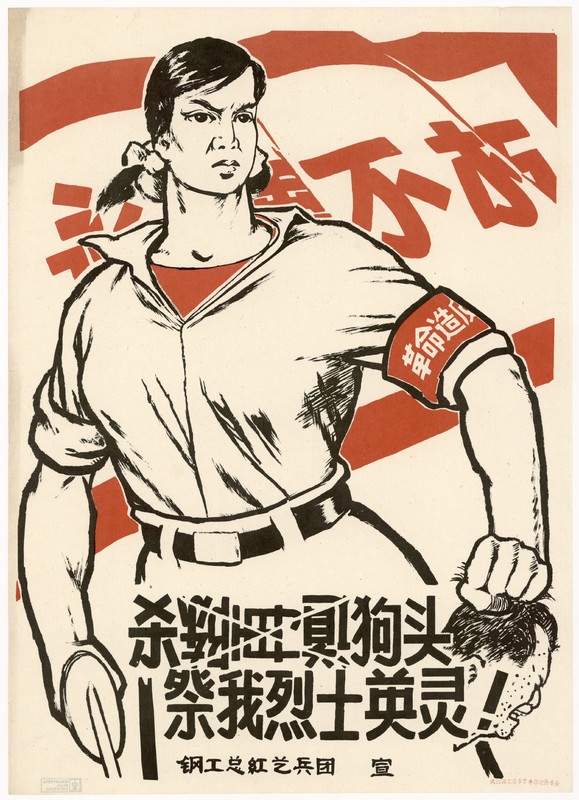

As Mao was still in the city, actually staying in another section of the East Lake Guesthouse not far from where Wang Li had been grabbed and beaten, central leaders in Beijing had grown increasingly concerned for his safety in what was looking like a potential military mutiny. Mao himself had decided that Wuhan had been swept into a “counter-revolutionary riot” by Chen Zaidao and the Million Heroes, and sought to rectify the situation. On July 21 at 2:00am, Zhou Enlai successfully arranged for Mao’s departure out of Wuhan, where conservative demonstrators had taken the rebel organizations by storm, leaving only four of five colleges still in rebel hands. The Million Heroes, still believing themselves to be in the favor of Mao, had begun planning to once again seize power in Wuhan and solidify the conservative position. However, by July 21 the center was already setting into motion a propaganda machine to crush the conservatives in Wuhan. On July 23 the Central Broadcasting Station and all the national newspapers initiated a campaign condemning actions taken by the Million Heroes in Wuhan. The next day, after the former leadership of the WMR had been corralled in Beijing, huge demonstrations were held by the CRSG in Tiananmen further denouncing “Wuhan reactionaries” (Wang, 2007: 262). These demonstration culminated in a joint denouncement at Tiananmen by Zhou Enlai, Chen Boda, Kang Sheng, Jiang Qing, and Lin Biao, marking the only time in the history of the People’s Republic that central leaders gathered together to condemn a local incident (Wang, 2007: 262). These messages shattered the conservatives position, and their view that they were the ones’ truly favored by the center. Their dissonance was so strong that they even considered momentarily whether Lin Biao, Mao’s second-in-command during the Cultural Revolution’s opening stages, had gone against Mao and the Cultural Revolution’s true intentions. Regardless of these thoughts, the position of the center had been made clear to both the WMR and the Million Heroes. By July 27th, the Million Heroes had completely collapsed, and the rebels once again reorganized and surged into the streets. As the rebels took control over the city, they brought down violent retribution on the members of the city’s conservative factions. Throughout July and August, “public accusation meetings were held in every unit, and hundreds and thousands of people paraded through the streets day in and day out” (Wang, 2006: 265). From the organizations leadership to its grassroots activists and regular members, all those who had participated in the Million Heroes were liable to be tortured, have their homes seized, and their family members abused. While statistics are incomplete it is said more than 600 people were beaten to death and over 66,000 injured or crippled in the days following the incident.

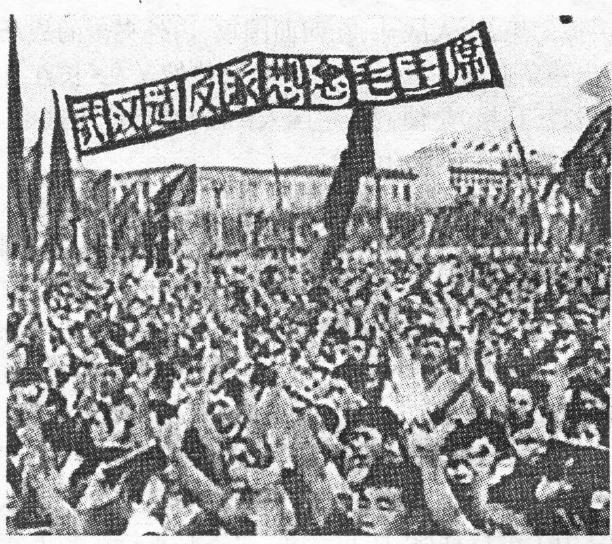

Students Welcome Xie Fuzhi and Wang Li Back to Beijing

This photograph depicts part of the center's propaganda campaign following the incident to validate the positions of the rebels by reconfirming its support of Wang Li and Xie Fuzhi.

While the rebels had certainly won the day, thanks to the decisions made by the central leadership, their one-sided victory turned into a bloody and brutal affair which would leave a mark on Wuhan and on the future of the Cultural Revolution. Despite the Million Heroes being crushed, conservative elements in the city were by no means eliminated, and factional strife continued in Wuhan up until the reform era as a result of the fissures opened in the 1960s. What became clear to Mao, and to the Cultural Revolution’s leadership, in the years to come was that Chen Zaidao and the Million Heroes had never intended to provoke an open rebellion against the center. The incident, as tragic as it was, had grown out of long existing tensions but was ultimately a product of miscommunication, misunderstanding, and simple chaos, exacerbated by the failure of the center to grasp the complexity of the situation. The continuation of violence in Wuhan, and other cities similarly shaken by the rise of the Red Guards during the 1960s, would go on to eventually motivate Mao and other central leaders to attempt to turn the tide of the Cultural Revolution, although by that point it was too late for many.