Revolution and Reincorporation

Starting with Wuhan’s own Wuchang uprising which cascaded into the 1911 Revolution, the early 20th century in China saw witness to a growing nationalist tide, manifested in growing resistance factions and violent uprisings. During this period the concessions played a contradictory role in defending rebels against attacks (first from the Qing government and later by a procession of warlords) while also serving as a powerful symbol of the continued exploitation of China by imperialist powers. By 1927 all but the Japanese and French Concessions remained, the rest had been returned in acts of opportunistic nationalism on the part of fervent rioters and various Chinese governments.

By the time Zhang Zhidong had left for his new post in Beijing in 1907, the Chinese parts of Wuhan had been transformed with modern schools, modern industries, and a modernized Hubei New Army. All these features had been instituted in Zhang Zhidong’s drive to preserve Qing governance through the Self-Strengthening movement, which involved the adoption of western technologies and practices to improve China’s ability to defend itself. However, amongst these institutions – particularly the new schools which educated young officers and officials, often sending them abroad where they gathered and organized around new governance practices for China – grew the seeds of revolution (Esherick and Wei, 2014). While many of the participants in the Wuchang uprising were New Army military officers and soldiers, two of Wuhan’s largest rebel organizations were constituted of intellectuals and named the Literature Society (Wenxueshe) and the Forward Together Society (Gongjinhui). On October 9th a bomb maker from one such rebel group caused an accidental explosion in their safe house located in the Russian Concession (Esherick and Wei, 2014: 107). The ensuing fire drew Qing government attention, who organized a mass sweep of the city seeking out similar activities (Courtney, 2013: 83). This spooked the revolutionaries entrenched in the New Army into the mutiny which took over Wuchang during the next two days.

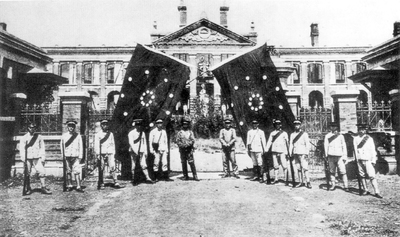

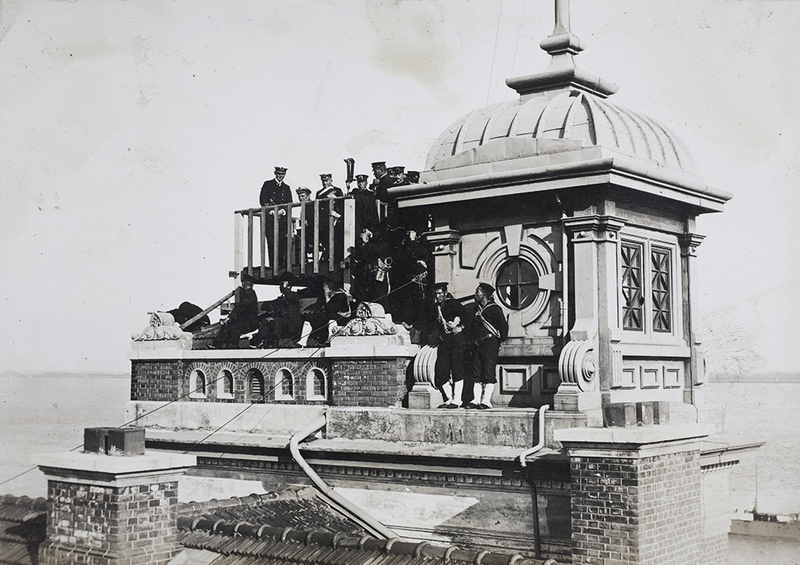

The following Yangxia campaign was devastating and brutal for the Chinese inhabitants of Hankou, whose city was burned almost completely to the ground in the ensuing fighting. This destruction was documented by photographers based out of the concessions, who followed the combat around the city capturing scenes of weary combatants, demolished buildings, and burning landscapes. Others captured the spectatorship of fellow foreigners, crowded on rooftops in international crowds of British, German, French, and Japanese onlookers gazing off into the fighting. The arrangement of the concessions’ streets and the large brick and stone houses protected the concession from fire while walls and barbed wire excluded fleeing soldiers and refugees alike (Courtney, 2013: 84). Despite both Qing and rebel forces avoiding directing fire towards the concessions out of fear of international reprisals, the concessions’ inhabitants felt the need to fortify its outer streets with sandbags and by October 17 fifteen foreign warships had gathered in the river to protect inhabitants (Neild, 2015: 111). After six weeks 300 British troops from Hongkong followed by 200 Russian troops and a regiment of Japanese secured the concessions’ defenses from the local volunteers.

Such circumstances would repeat themselves, albeit on a smaller scale, during the July 30 incident following the consolidation of the warlord Wang Zhanyuan’s regime in Hubei. After the death of Yuan Shikai, the Beiyang general appointed to Hubei province, Wang Zhanyuan, took control over the region politically and militarily using his division of the Hubei army. In order to eliminate future resistance, Wang leveraged his position as a stabilizing force to convince Wuhan’s more moderate anti-monarchist rebels to step down and surrender their arms, many exiting the foreign concessions where they had made their bases (McCord, 1993: 238). Despite the settlement offered by Wang, which promised free passage for revolutionary leaders and followers out of Hubei, many of the more ardent rebels, particularly those associated with Sun Yat-sen, refused to set down their arms. Wang then negotiated with concessions’ leadership about forcedly expelling the remaining rebels, an action which forced the remaining few hundred men to arms. On July 30th the unorganized mob spilled out into the native city, rioting and destroying property, until they were violently quelled by Wang’s forces. Foreign photographers were again at the scene, capturing the horror and destruction brought to Hankou’s native city during the warlord period.

However, rebellion and revolution were not the only manifestations of new Chinese nationalism seen in Hankou since 1911, as the foreign concessions themselves were now viewed by many as the embodiment of the unequal relationships formed between foreigners and Chinese natives in business, labor, and politics. The first of Hankou’s concessions to be returned was the Germans, taken in part due to Germany’s preoccupation with World War I. The Beiyang government under the Duan Qirui and others in the Zhili clique declared war on Germany in August 1917 citing the opportunities of reclaiming undefended German possessions in China and securing a spot at the negotiating table after an Allied victory (Sun, 2004: 101). The declaration of war further offered the opportunity to shore up popular support for the Zhili warlord faction by salvaging Chinese pride after years of exploitation by foreign powers. The declaration sent shockwaves through the German community in the concession, and the German consul refused to surrender the concession to local Chinese authorities. However, the Beiyang government promised local German residents that their property would be protected, and chose to preserve foreign local governance to some extent through the establishment of Hankou’s first Special Administrative District (SAD) (Neild, 2015: 104). The concession was formally succeeded in 1919 following the end of the First World War, and remained a SAD up until January 1929 when it was finally placed under the administration of the Hankou city municipality.

The Russian concession followed a different route, with a relatively willing national government offering the surrender of the concession, followed by unilateral action on the part of the Chinese government and local resistance by concession residents. While the Beiyang government in Beijing initially refused diplomatic recognition to the ascendant Bolshevik regime in Russia following the October Revolution, China’s humiliation at the Versailles Conference made Bolshevik messaging more appealing. In July 1919 the Soviet government issued the First Karakhan declaration, offering equal treatment to China and the succession of all unequal treaties (Eiermann, 2005: 45). While offer did not prompt the Beijing government to recognize the Soviet government, it did prompt them to abolish all of the extraterritorial rights of White Russians in China on September 23, 1920. This was received positively in Moscow, which responded with the Second Karakhan declaration, reiterating the content of the first, on Semptember 27, 1920. Following this, the Beijing government, still not acknowledging the new Russian government, issued orders to the Hubei warlord government under Wang Zhanxuan to retake the Hankou Russian concession. Despite attempts by local Chinese police to take the concession back, the area was successfully defended by English, French, and American police. The French consul went as far to declare on October 8th that the Russian concession was part of the French concession, and Chinese negotiators would have to work with French officials (Eiermann, 2005: 46). The combined police forces of the concession succeeded in repelling Chinese attempts to take the land three more times, demonstrating a resolve potentially motivated out of fears that the return of one concession would be followed by others. Following this the Beijing government once again attempted to placate residents with the establishment of the second SAD on September 23rd, 1920 (Neild, 2015: 104). In August of 1922 Soviet representative Adolf Joffe arrived in China and – due to the competition between Sun Yat-sen’s southern government and the Zhili clique’s northern one – he was finally invited to Beijing in September of 1923, resulting finally in the Sino-Soviet Treaty of May 31, 1924 which formally succeeded the Russian concession in Hankou. Despite the Soviets’ official return of the concession, they retained ownership of a large portion of the land and the buildings constructed atop it, and via secret agreements made with the nationalist government in 1929 and 1939 actually continued Russian extraterritoriality and consular jurisdiction within the concession (Eiermann, 2005: 47). Whether this was a continuation of Tsarist imperialism or an extension of communist internationalist ideology necessitating bases for world revolution is debated, however it is clear that the physical, human, and administrative qualities of the Russian concession continued on long after its official reintegration.

The British concession was the next to fall, this time by indigenous mass mobilization instead of a top-down decision making. During the mid-1920s tensions had continued to rise between British factory owners, police, and concession officials and Chinese workers and students seeking better working conditions and reprisals for imperialist exploitation (Chan, 1998: 138). Massive demonstrations held by organized labor were responded to with concession police violence, including an incident in 1925 where a machine gun was trained on a crowd killing nine and wounding more than ten protestors. The concessions continued to be supported by British and Japanese warships positioned in the Yangtze, along with the concessions’ police forces and volunteers. However, circumstances changed when the Northern Expedition reached Wuhan in autumn of 1926, taking Wuchang after a month and causing refugees to spill into the concessions fleeing the fighting. Fearful concessionary officials had the machine guns placed on the Hongkong & Shanghai Bank and the Customs House in order to protect against what some saw as an impending attempt by the Nationalists to retake the British concession (Neild, 2015: 115). The arrival of the nationalists in Wuhan had caused a boom in the region’s long-repressed labor organizations, who now received government support in their fights for improved wages and conditions in Hankou’s industries – both foreign and Chinese alike. The newly invigorated labor movement sought to confront the long-standing symbol of British imperialism manifest in the concession and in late December 1926 a quarter million people attended an anti-British rally demanding the return of the concession (Chan, 1998: 138). In January 1927 New Year celebrations turned into another wave of mass demonstrations, leading the British to further fortify the concession and station Royal Marines off the warships in the Yangtze in the concession to defend it. On January 3, 1927, an altercation resulted in a British soldier killing a Chinese unionist and wounding several dozen other Chinese in the concession (Chan, 1998: 138). The following morning labor leaders organized a massive turnout of workers and city inhabitants who rushed the British concession demanding the British vacate. They were met by the Royal Marines armed with rifles and bayonets, and a standoff ensued (Neild, 2015: 115).

As the larger foreign warships had been forced down the Yangtze due to low tides, concessionary forces had little support and began fortifying the Asiatic Petroleum Co. building on the Bund – which was considered defensible and had easy access to escape via the river. Foreign banks and businesses were shut down, and women and children were encouraged to flee by whatever means necessary, those left on the bund congregated inside of the Asiatic Petroleum Co. building and awaited help from the Nationalists. The Nationalists, who had responded to this turn of events with the establishment of a Committee of Administration for the concessions, presented the British with the ultimatum that if the Royal Marines were returned to their ships and the Hankou Volunteer forces were disbanded, Chinese troops would take control of and protect the concession. These terms were accepted on January 5th, the day they were extended, and the British Concession was returned to Chinese hands – the first instance of British retrocession in China. Amongst the British community remaining in Hankou there was considerable fear and resentment regarding the loss of British prestige and what lay ahead in the future – with their own residential Hankou Volunteers having been disarmed by the British navy’s Marines. British Consul Herbert Goffe began negotiations with the Nationalist government’s Foreign Minister Eugene Chen Yujen, and was joined by Owen O’Malley – sent to represent Sir Miles Lampson, the British Minister in Beijing. On the 27th of January O’Malley, with orders from Lampson, issued a statement to both Chinese governments in Beijing and Hankou that the British would accept the extension of Chinese law to British subjects in China if the issue of the concessions in Hankou and Jiujiang (which was also taken in a similar fashion) was resolved. The subsequent Chen-O’Malley Agreement of February 19th, 1927 transferred the British Concession to Chinese hands as the 3rd Special Administrative District, preserving to some extent British properties and administration. While business was slowed during 1927, trade returned to relative normality in 1928, as foreigners still faced no Chinese taxes and the treaty port system continued to be maintained (Neild, 2015: 116). British administrative control was even maintained to some extent under a new municipal council with three British and three Chinese councilors underneath a Chinese director.