Key Hankou Products

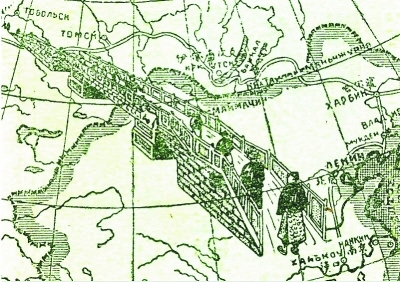

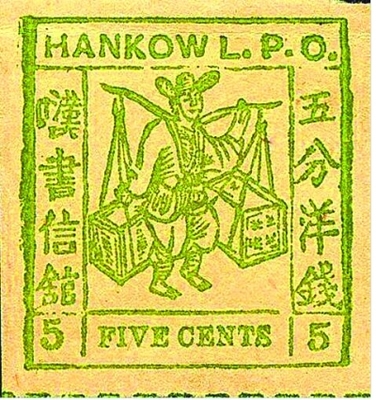

In the twentieth-century Hankou became famous for its industry, often dubbed the "Chicago of China". But Hankou had a long history in trade well before the establishment of the concessions and the growth of industry. Since its establishment, Hankou had acted as a port and distribution center for goods, but the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries marked an intensification of trade across China which greatly benefitted Hankou. During this period trade expanded beyond luxury goods and staples, such as salt, to a diversification of goods traded and an increase of goods in general. Hankou's position in exporting to the lower Yangtze was tranformative. Hankou was the center distribution point for 360 distinct commodities in the nineteenth century. It was celebrated for its Eight Great Trades: grain, salt, tea, medicinal herbs, oils, hides and furs, cotton, and tsa-huo or Cantonese and Fukinese miscelleaneous goods. The Salt Trade was especially important for the ways in which salt merchants held an elite and influential position within the city. Additionally, the Tea Trade was part of the West's interest in Hankou; Hankou's central location in the tea trade was especially appealing to westners who sought to establish concession and get a piece of the trade. Additionally beans, hemp, sugar, and vegetable wax were important trade goods. Coal was brought into the city by returning salt boats. And Parrot Island, in Hankow harbor, was the largest wholesale bamboo and timber market in the empire. There was an intricate division of labor within Hankou, including merchants holding a very particular role within the commercial chain. The establishment of the foreign concessions in Hankou added more voices, more goods, and more trade to an already well-established, complex, trading port.

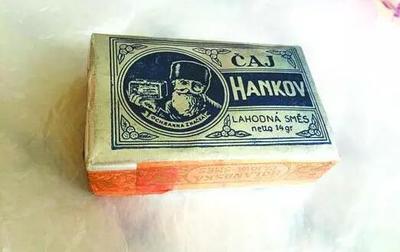

Tea Trade:

The tea trade played an important role in Hankou since the city's formation. Intially the trade in tea in Hankou was a domestic trade, it then expanded north to trade in Russia, Siberia, and Mongolia via the Han River. In the early nineteenth-century tea trade with Russia increased enormously; tea became the principle Chinese export to Russia. (Later the industrial production of tea bricks led by Russians played an important role in Hankou's economy). After 1842, trading dynamics shifted throughout China and Hankou took on an even greater share of the tea trade. For Westerns, tea trade was Hankou's raison d'être; the desire for greater access to the tea trade influenced the opening of Hankou to foreign concessions and trade. Chinese officials and tea merchants contested with Westerners in the early 1860s for the ability to organize and tax the trade. Westerns often saw this as creating monopolies or violating treaties but for local officials and merchants it was a means of guarding their benefits in the trade.

Salt Trade:

The salt trade, like the tea trade, was a defining aspect of Hankou. Hankou served as a major depot for the Huai-nan region; salt was brought to Hankou, dutied, repackaged, and sent out again. During the nineteenth-century there was a fair amount of competition with Szechwan due to changes in goverment regulation of the trade and the presence of salt smuggling. Both the official trade and the smuggling depended on a system of waterways in the region, of which Hankou was situated on a key location, an ideal crossroads for a port. By the early twentieth century salt no longer dominated Hankou's trade but it continued to play an important role, and continues so today.