Warlords, Workers, and World War II

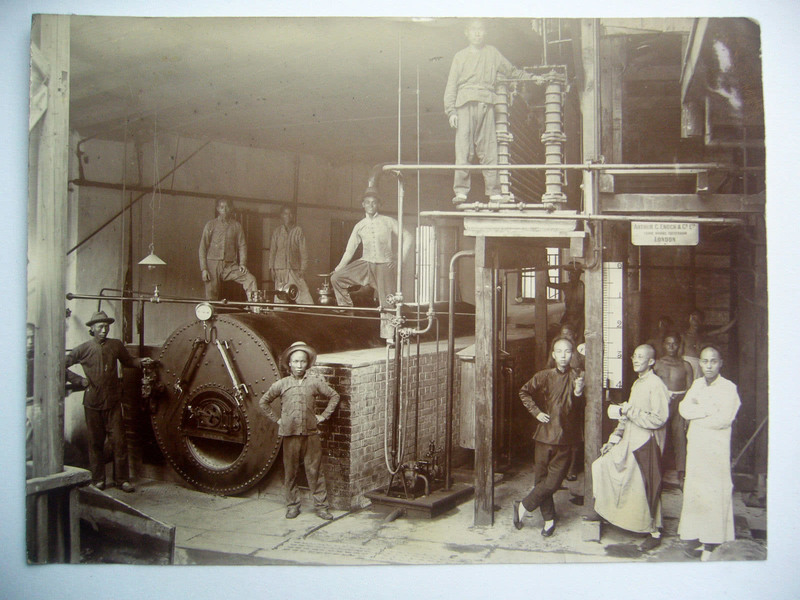

In Wuhan’s cotton industry alone, by 1915 there were over 300 privately-owned factories employing nearly 12,000 workers, and throughout the 1890s and 1900s the city’s working population had grown to an all-time high. Many had migrated to the city for work from rural areas, and as new construction often failed to keep up with the flow of new people, they were forced to settle in shanty towns and hutments built on the outskirts of the city (Spence, 1990: 247). The jobs they found offered poor wages and terrible working conditions, forced to breathe in the dust produced by crushed sesame seeds or poisonous white phosphorous. While the advances of Wuhan’s industrialization may have brought a degree of security to some, certainly those who had benefited directly off the explosion of certain enterprises, to many others the city’s new features brought calamity instead of riches. Some of Hankou’s earliest organized strikes occurred during this period, with copper workers striking in 1905, mint employees in 1907, and thousands of street vendors, hawkers, stall-keepers and shop assistants following suit in 1908. Within Wuhan’s factory environment two new powerful forces were forged: the weapons and supplies that fueled future wars and revolutions, and the labor organizations bent on political change.

In 1911 tensions surrounding foreign exploitation began to manifest themselves with greater frequency and explosivity within Hankou and its neighboring cities. On the 23rd of January, a rickshaw driver who was supposedly ill was taken by British police into the municipal council building. When the man died concerns were immediately raised by other drivers that the police had kicked him to death, inciting a mob of around 3000-4000 who proceeded to attack the Hongkong Shanghai bank on the bund (Neild, 2015: 111). This more specific attack was partially motivated by knowledge that bank’s chief broker was responsible for unfair loans to Chinese railway developers. The mob overwhelmed concessionary police and was only forced back when troops from British and German gunboats in the Yangtze were ordered to shore. By this point however another mob of between 20,000 to 30,000 people had organized at the south end of the concession and began to try and break into the Customs House. As the mob began to move further into the British concession Marines organized off of one of the British ships were ordered to fire on the crowd, killing 30-40 people.

While tensions were flaring in the concessions, resentment towards the Manchu rulers of the Qing dynasty had been fermenting in the ranks of the Hubei New Army, who had been organized by Zhang Zhidong around a modern educational system which had facilitated the spread of seditious thought. These ideas were brought to the forefront during the October 1911 revolution, when mutinying New Army troops took over Wuchang and declared a revolutionary military government. The first act of the governor-general Ruicheng, after escaping aboard a gunboat in the Yangtze, was to order two gunboats to defend the arsenal. Sheng Xuanhuai, now the Hubei government’s Communications minister, was said to have promised troops great rewards if they were to defend the Ironworks and Arsenal, the former of which was still his own enterprise (Feng, 2013: 115). Despite their keen awareness of the importance of both Arsenal and Ironworks, both men were limited by the fact that the majority of the New Army had sided with the rebels. Soon the Ironworks and Arsenal were in the hands of the rebels, manufacturing and distributing the rifles, ammunition, and artillery which would be used to fight the Yangxia campaign against the Qing. The specific rifle manufactured at Hanyang was German based, five-shot 7.9 caliber rifle. Simple in design and built in-country, the Hanyang Rifle, as it became known, soon grew famous for its role not only in the 1911 Revolution but as a tool of Nationalists and Communists alike, fighting against each other and later against the Japanese. The following battles would destroy the native city of Hankou, but a significant portion of the tri-city’s manufacturing capacity would be preserved in Hanyang and Wuchang, which were both not nearly as devastated

As the 1911 Revolution gave way to the rise of warlords like Wang Zhanyuan, who would control Wuhan and surrounding Hubei province up until the Northern Expedition reached the city in 1927, the weapons of the Hanyang Arsenal were frequently turned against the labor agitators who advocated for those producing them. Wang’s position in Wuhan was solidified in 1916 with the violent suppression of the city’s remaining anti-monarchist elements who had risen up against Yuan Shikai, and his troops, a portion of the Beiyang army formerly under Yuan, were armed with rifles produced in Hanyang. The location of the Hanyang Ironworks and Arsenal certainly bolstered the position of Wang as warlord of Hubei, but beyond the military value of the instillation Wang had little interest in factories. As Hubei and Hunan elites grew irate with the inadequacies of Wang’s military government, one of Wang’s advisors recommended he work to develop new factories and schools, to which he responded, “Look at the presidents and premiers of the central government and at the heads of each province. Which has given any thought to national construction? These past years I have had to work without rest, day and night, attending to the large armies pressing Hubei’s borders. When do I have time to pay attention to things like industry or education?” (McCord, 1993: 274). This attitude was certainly not conducive to the industry development experienced under Zhang Zhidong, although many foreign and private firms still thrived in this period, in part potentially to Wang’s violent suppression of labor organizations as threats to his regime.

Following Wang’s fall in 1921 and the rise of Xiao Yaonan – a Hubei native – as Wuhan’s new warlord, labor activists breathed a new wind and many set to work organizing against Wuhan’s most prolific industrial issues. In 1925, news of the May 30th movement in Shanghai spread to Hankou, resulting in a May 23rd walk-out at the British-American Tobacco company regarding newly introduced machinery (Neild, 2015: 113). This was followed a day later by a strike at an egg-processing plant regarding inadequate wages, and another at a match factory in the Japanese concession. On June 3rd two substantial labor organizations – the ‘Wu-Han People’s Diplomatic Association’ and the ‘Association for Hastening the Citizens’ Conference’ – began mobilizing support for strikers. This resulted in an additional eight walkouts of foreign owned factories, and on June 6th these workers were joined by 25,000 students, raising concerns in the concessions for the safety of foreigners on the streets. Several days later on June 10th, a confrontation between two stevedores employed by Butterfield and Swire – a major trading firm located to the south of the British concession – escalated the next day into the full occupation by protesting workers of the B & S compound. As the crowd began to move on the concession, police were assisted by Royal Marines who again forced the laborers to disperse. When later that evening the workers regrouped near the bund they were set upon by police and foreign volunteers, who opened fire on the crowd with a machine gun, killing four. The violence led to an abrupt end of the strike, and the warlord government responded by executing a number of “Bolsheviks and other undesirables” (Neild, 2015: 114).

By January 1927 however the situation had changed dramatically. The Northern Expedition had reached Wuhan, and the city was declared the new capital of the First United Front government (MacKinnon, 2000: 165). Amongst the leaders based out of Wuhan were Wang Jingwei and other members of the Guomingdang’s left wing, who sought to gain support amongst the city’s well-organized labor and student groups by rallying behind the flag of anti-imperialism. This support manifested when new years celebrations turned into mass protests against British imperialism, sparking mobs to storm the British concession which was defended by British troops (Chan, 1998: 138). On January 3rd a Chinese unionist was killed in a confrontation with a British soldier, and the next morning Chinese picketers organized a massive rally which then rushed the British Concession. The British, forced to retreat, eventually negotiated the surrender of the concession in February of that year. Despite such triumphs, the Wuhan Nationalist government was short lived, being crushed after Chiang’s forces based out of Nanjing moved against the United Front’s left. The city was then relinquished to Guanxi warlords who continued the brutal repression of student and labor organizations. Heavy-handed economic policies between 1927 and the 1930s, coupled with the effects of the Great Depression, severely crippled Wuhan’s economy and endangered the lives of its workers. As the Guomingdang’s control over the city grew during the 1930s under General He Chengjun, conditions for workers and labor organizers only worsened. Yang Qingshan, a mobster paid by He to target political enemies and dissidents, killed hundreds of alleged Communists in 1930, having 19 executed directly in front of the Jianghan Customs House in Hankou.

In 1938 however, past decades of industrial stagnation were brushed aside as Wuhan was transformed into the wartime capital of China’s United Front government. As the Nationalist government staged its strategic retreat up the Yangtze, combat losses of men, machines, and arms meant Wuhan’s native production facilities were working overtime to meet with demand. Meanwhile, other factories had been back up and moved inland, arriving from the coasts in incredible numbers. By spring of 1938, around 170 factories from near Shanghai had been re-established in Wuhan and were already operational, bringing with them their machinery as well tens of thousands of skilled laborers (MacKinnon, 2000: 170). Despite this massive wartime push, and the considerable effort and costs dedicated to the war effort by all those involved, Wuhan’s wartime industrial production peaked just as Japanese bombing raids began to cut into the city’s industrial capacity in March of 1938. As the Japanese moved closer and closer up the Yangtze, the principal concern of Wuhan’s military planners was how to move the city’s existing machinery, weapons, and parts further inland, or else destroy it before it could fall into the hands of the Japanese. Weng Wenhao was appointed by Chiang Kaishek to oversee this massive process of dismantlement and demolition, and his Industrial and Mining Adjustment Administration began to take apart the Hanyang Ironworks and Arsenal piece by piece, moving the body of Wuhan’s heavy industry up the Yangtze to Chongqing. The summer months under siege saw the vast majority of Wuhan’s state-owned enterprises, from the cotton mills to the hydroelectric plant, disassembled and relocated at massive expense. These were followed in the autumn by privately owned companies like textile mills, cigarette factories, and food processing businesses, which all proceeded further into the interior. By October around 57% of the city’s productive capacity had been moved inland, including more than 108,000 tons of equipment, 10,000 workers, and a total of 13 heavy industrial plants and 250 light industry units (MacKinnon, 2000: 170). When the Japanese arrived in the city in October over 70% of the city’s industrial capacity had been moved or destroyed, not to mention the laborers and knowledge necessary to operate such facilities. In the wake of World War II, when American bomber raids as part of Operation Matterhorn destroyed large swaths of Hankou and all but demolished the industrial areas of Hanyang and Wuchang, the formally industrious Wuhan was a shadow of its former self. The city would not recover its status as Central China’s industrial heart for two decades.