Reimagining the Bund

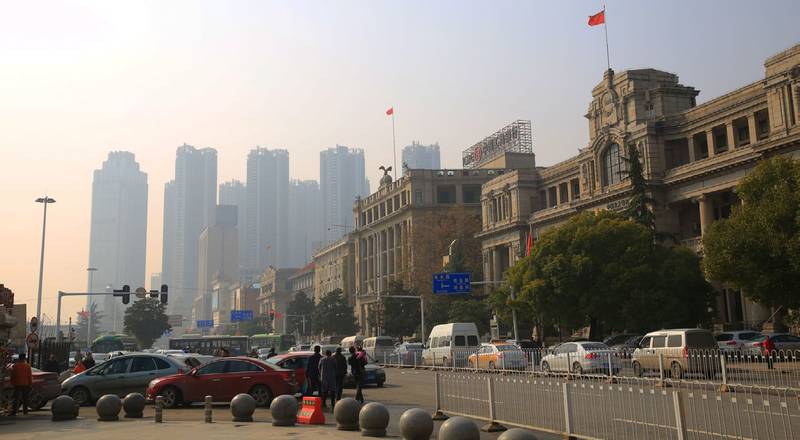

While the last of Hankou’s foreign population had left following the ascendance of the CCP across China, the buildings they left behind have remained, becoming integrated into Wuhan’s constantly changing cityscape. When the Communist Party’s municipal government was founded in 1949, it adopted a policy of full utilization and gradual transformation towards the former concession areas which continued up until the late 1970s (Cheng et al., 2017: 437). While the city’s government struggled with funding and a lack of available work and residential spaces, it began moving city residents and their jobs into the mansions and former office buildings on the Bund. Some buildings, particularly the old warehouses where tea had been stocked decades before, were converted into housing and dormitories, with interiors modified to suit the needs of their new inhabitants. The some of the prestigious banks and company headquarters which had previously lined the bund were filled with government institutions. Throughout this period the physical layout of the streets, and even the facades of the buildings themselves remained relatively unchanged, slowly decaying without proper maintenance up into the reform period. When the market reforms hit Wuhan and capital began to flow in from abroad, there was new incentives to revitalize Hankou’s downtown area with new construction projects to house the city’s growing enterprises. Starting the 1985, the local government of Jiang’an district – where the concession was located – initiated a redevelopment project which involved tearing down a number of “traditional” treaty-port era Lifen units to be replaced with a commercial-residential complex (Cheng et al., 2017). As the city opened further to foreign businesses and entrepreneurs, demand for modern sky-rises also grew. From 1990 to 1991, the Wuhan city government set out on another redevelopment project targeting decrepit and endangered housing to be converted into residential quarters. As part of this program the old French police station was demolished, along with a number of other historic buildings to be replaced by modern towers.

From this new initiative to modernize Hankou’s cityscape came an equally powerful response from scholars and conservation authorities demanding that the area be preserved and its buildings protected. These activists effectively push the state government to issue in 1982 the Law on the Protection of Cultural Relics, which created a program through which the state identified significant historical sites for preservation. The law created a three-tier conservation system which listed buildings, areas, and cities with considerable historical value and laid out guidelines for local governments to protect such resources (Cheng et al., 438). In Wuhan this process has involved a constant back and forth between advocates for historical preservation and those seeking to modernize the city’s downtown. While legal barriers were developed over the 1990s and 2000s which were rigorously employed by certain sections of the city’s government, other officials have been far more lenient with developers, permitting the wholesale destruction of entire blocks of historic buildings. Scholars concerned about the destruction of the area’s historic skyline have been joined by the public in resisting government efforts to “revitalize” historic districts. In 2009, after the Wuhan municipal government announced its plans to demolish a number of buildings in the former British Concession in order to construct a new subway, citizens of Wuhan organized on line and launched a conservation campaign for the area. Others have taken the route of adapting and restoring old concessionary buildings into economically productive spaces, contributing to their conservation. In the former British concession many historic buildings have been turned into lucrative and chic coffee shops and bars. In the Russian concession, a number of freelance artists have converted old warehouses into studios and galleries, creating an “artists’ village” to match with the region’s cosmopolitan history. However, while areas like the Russian and British concessions are being celebrated for their “international” history, the housing of many of the area’s Chinese residents have been the first structures to be demolished.

This perpetuation of a selective nostalgia of the city’s treaty port history is readily embodied in the revitalization project surrounding Hanzheng road – the main thoroughfare through the old Chinese city. This effort followed three phases, starting from 1987-1991 with the upgrading of dilapidated buildings and efforts to improve living conditions and the commercial environment (Law and Qin, 2018: 10). This was followed by phase two, which ran between 1991 and 1999 and combined marketized regeneration of spaces combined with real estate and property development. The final phase, from 2003 to present, was pursued by the government to preserve the “traditional characteristics” of the street. These revitalization efforts involved the placement of 18 statues along the thoroughfare meant to represent the history of Hankou’s port development (Law and Qing, 2018: 8). Amongst these brass figures are representations of workers carrying cargo boxes, representing the loading of goods upon foreign ships for export, a colonial official and an affluent couple in republican-era apparel, symbolizing the tides of wealth and prosperity which have swept over the cosmopolitan Hankou (Law and Wing, 2018: 8). Embedded within these statues, and integral to the efforts of the city government in placing them along the newly revitalized Hanzheng road, is a powerful nostalgia which blankets over the more troubled periods of the city’s history. Along this very street labor organizers, surging with anger over imperialist exploitation, had rushed into the British concession to be gunned down by Royal Marines. On the same stretch of road in the 1960s, the Million Heroes faction had clashed in bloody street battles with rebel factions (Law and Qing, 2018: 11). In returning Hankou’s streets to an idealized past, the Wuhan government, and many of the citizens enjoying this newly created space, engage in an active forgetting of the more uncomfortable narratives which shared the same space.