The Legacy: Arab-American racialization into the 21st century

Impact of the Dow Decision

The decision in the final Dow case reflects a larger trend among the American courts regarding racial classification. At the turn of the century, immigrants utilized scientific, religious, and cultural arguments to secure whiteness. However, by the time of Dow, more judges were beginning to rely on congressional intent and common knowledge to determine who was defined as a white person. Following the decision of Dow v. United States, debates regarding the racial classification of Syrians temporarily subsided. The case had established a strong legal precedent for Syrian whiteness. It was this legal precedent set by Dow that ultimately protected Syrian immigrants from the increasingly restrictive immigration policies placed on Asian immigrants.[1] Because a strong precedent for classifying Syrians as white as opposed to “Asiatic” had been established, Syrian immigrants were able to avoid being targeted by laws such as the 1917 Immigration Act, which racialized the geography of Asia and Europe. The act greatly narrowed the bounds of whiteness and who was considered “acceptable” through the imposition of a literacy test. The act also barred immigration from parts of Asia through a “geographic exclusion zone.”[2] This act built upon previous anti-Asian policies, such as the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, by expanding restrictions to geographic zones as opposed to nationality or race. It is important to remember that the racialization of Syrians in the early 20th century did not function within a vacuum but was part of a larger project of restriction and classification of immigrants. Thus, the Dow cases and Syrian racialization are both also implicated in a larger history of American immigration restriction as well as anti-Asian and anti-Black policy.

Post-Dow Cases

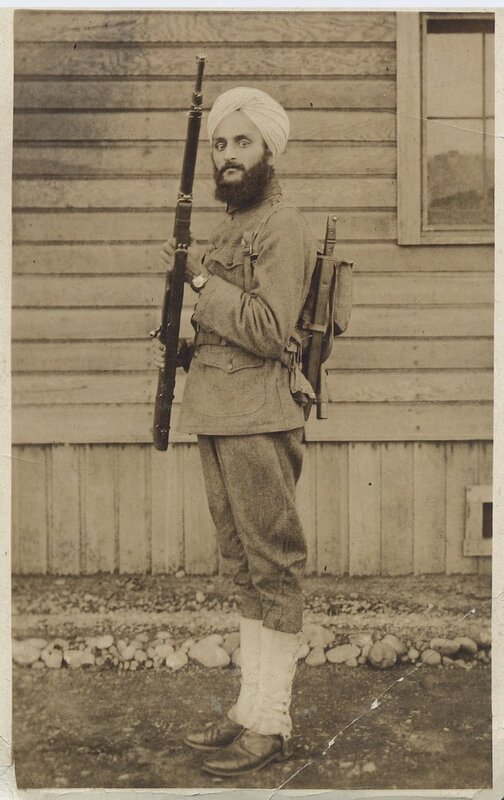

Although the decision in Dow v. United States had secured whiteness for Syrians, the same did not hold true for other immigrant groups. For example, in 1923, a Sikh man from Punjab India named Bhagat Singh Thind applied for naturalization, arguing that he was Caucasian/Aryan. Similar to many of the arguments presented in the Dow cases, they cited ethnology and race science as a basis for his whiteness. United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind was brought before the U.S. Supreme Court where it was ultimately ruled that immigrants from India were in-fact not white. Falling in line with the growing trend of turning away from race science and relying more heavily on congressional intent and common knowledge, the court held that Thind was “not a ‘free white person’ in the ‘understanding of the common man.’”[3] Similar cases for other immigrants also occurred. One year prior to United States v. Bhagat Singh Thind, the court had held in Ozawa v. United States (1922) that Japanese immigrants were not white either. As such, while some immigrants from the continent of Asia, such as Syrians, were able to maintain whiteness despite the courts changing approaches to racialization, the same did not hold true for other immigrants, such as those from South and East Asia.

In the early 1940s, Syrian racial classification would again be taken up by the American courts. In 1942, Ahmad Hassan, a Yemeni Muslim man, was denied naturalization. The main difference between Hassan and early Syrian applicants was his religious identity. While the courts held that Syrian Christians were white, the same reasoning did not seem to apply to Muslim immigrants. To justify the rejection, the court highlighted the physical appearance of Hassanm, similar to Bhagat Singh Thind, they argued that he was “undisputedly dark brown in color,” highlighting that in cases when the applicant was deemed “unassimilable,” skin color could function as evidence.[4] The court further argued that “Apart from the dark skin of the Arabs … it is well known that they are a part of the Mohammedan world and that a wide gulf separates their culture from that of the predominantly Christian peoples of Europe.”[5] Although Christianity had already been shown in previous cases being Christian was not sufficient reason for whiteness, being Muslim was sufficient reason for non-whiteness. However, two years later, a case involving a Muslim Saudi Arabian man named Mohamed Mohriez complicated this decision. In this case, Mohriez’s affiliation with Islam did not seem to disqualify him from naturalization. The judge drew on linguistic and cultural arguments, stating that “the understanding of the common man the Arab people belong to that division of the white race speaking Semitic languages.” [6] Khoshneviss contextualizes this stark shift in views within the larger geo-political climate and American foreign relations with SWANA nations and the second world war.[7] These two cases show that even after Dow, Syrian racialization was still highly ambiguous and contested. Syrian immigrants occupied a liminal zone between white and non-white and their racialization by the law was in constant flux, “racialized into a paradox of visibility and invisibility.”[8]

Immigration and Naturalization in the Mid 20th Century

In 1952, American immigration law changed dramatically. Congress passed the Immigration and Naturalization Act (INA), which removed the racial bar for naturalization. However, as noted by Kelly Lytle Hernandez, the INA did preserve the national quota system and placed new limits on Asian and Black immigration. As such, the INA in many ways continued the legal precedent of racially exclusionary immigration laws. Immigration law was again changed in 1965 with the passing of the Immigration Reform Amendment (IRA), also known as the Hart-Celler Act. The act officially prohibited racial discrimination in the visa system and thus served to abolish the national quota system. However, this did not fully end racism and discrimination in the American immigration and naturalization systems, which continue to persist to this day.

SWANA Americans in the late 20th and 21st Centuries

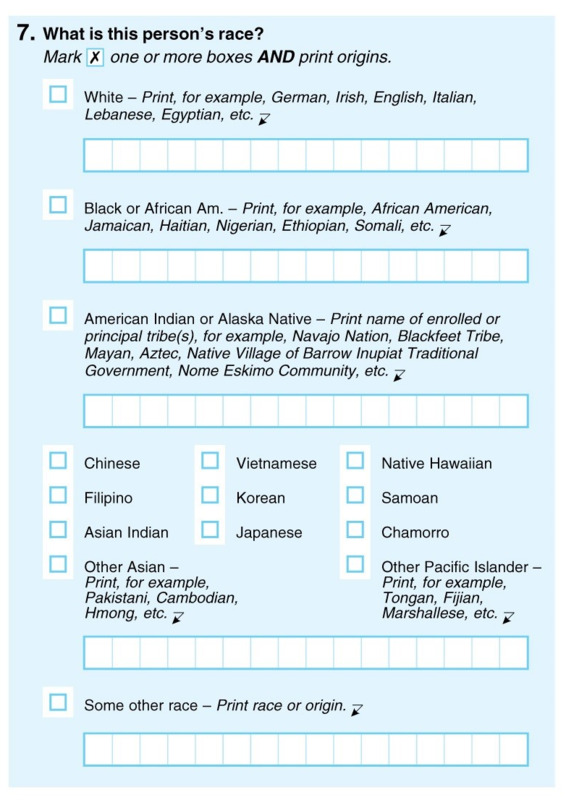

Although naturalization is no longer racialized, the impact of cases such as Dow is still felt today in SWANA communities. Despite procuring legal whiteness, many Syrian immigrants still faced racism, violence, and discrimination. For example, in 1929, Senator David A. Reed referred to immigrants from Syria as “the trash of the Mediterranean.”[9] Thus, even in securing legal whiteness, Syrian (and more broadly SWANA) racialization and otherness have persisted. Since the 1980s, SWANA activists have begun to push back against SWANA peoples' “whiteness.” Much of this push has been targeted towards the United States census which as of 2020 classified SWANA people as white. Advocates for the removal of SWANA from whiteness have emphasized SWANA experiences of discrimination and xenophobia which has dramatically increased in the United States since 9/11. In her book The limits of whiteness: Iranian Americans and the everyday politics of race, Neda Maghbouleh argues that immigrants from Iran while “white by law,” are “brown by popular opinion,” placed at the “limits of whiteness.” The same holds true for most SWANA Americans who, since 9/11 and the American War on Terror, have been the targets of further violence and discrimination. The biggest reason many have pushed for a MENA category has been related to equity and resources. As many have pointed out, the lack of a MENA category and the group of SWANA with white limits the resources available. Furthermore, the grouping of SWANA with white restricts the ability for federal organizations to collect data and address issues such as health inequalities and develop policies to increase representation, equity, and resource allocation. The categorization of SWANA people as separate also allows for the voices, experiences, and needs of the community to be made visible. A separate MENA category was almost added to the 2020 census after decades of activism, but in 2018 it was ultimately announced that the category would not be present.[10] United States representative Rashida Tlaib responded to this decision in an address to the Census Bureau Director in 2020. Scholars and activists have continued to fight for a MENA category as a crucial first step in achieving social and health equity.[11] In 2024, the U.S. Office of Management and Budget officially announced new federal standards for “maintaining, collecting and presenting race/ethnicity data across federal agencies.”[12] Part of these new standards was the addition of a Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) category which in turn will officially be added to the 2030 U.S. Census.[13]

[1] Amaney A. Jamal and Nadine Christine Naber, Race and Arab Americans before and after 9/11: From Invisible Citizens to Visible Subjects, 1st ed., Arab American Writing (Syracuse University Press, 2008), 161.

[2] Dhillon, “The Making of Modern US Citizenship and Alienage,” 17.

[3] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 74.

[4] Khoshneviss, “Accruing Whiteness,” 630.

[5] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 158.

[6] Khoshneviss, “Accruing Whiteness,” 631.

[7] Khoshneviss, “Accruing Whiteness,” 631.

[8] Sarah Abboud et al., “The Contested Whiteness of Arab Identity in the United States: Implications for Health Disparities Research,” American Journal of Public Health 109, no. 11 (2019): 1580, https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2019.305285.

[9] Khater, “Arabs in America,” 13.

[10] Loubna Qutami, “Censusless: Arab/Muslim Interpolation into Whiteness and the War on Terror,” Journal of Asian American Studies (Baltimore, United States) 23, no. 2 (2020): 161–200, https://doi.org/10.1353/jaas.2020.0017.

[11] Ken Resnicow et al., “Looking Back: The Contested Whiteness of Arab Identity,” OPINIONS, IDEAS, & PRACTICE, American Journal of Public Health (Washington, United States) 112, no. 8 (2022): 1092–96; Abboud et al., “The Contested Whiteness of Arab Identity in the United States.”

[12] Rachel Marks et al., “What Updates to OMB’s Race/Ethnicity Standards Mean for the Census Bureau,” Government, Census.Gov, April 8, 2024, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2024/04/updates-race-ethnicity-standards.html.

[13] Marks et al., “What Updates to OMB’s Race/Ethnicity Standards Mean for the Census Bureau.”