The Historical Context : Early Syrian Immigration and Racialization

Early Syrian Immigration to the United States

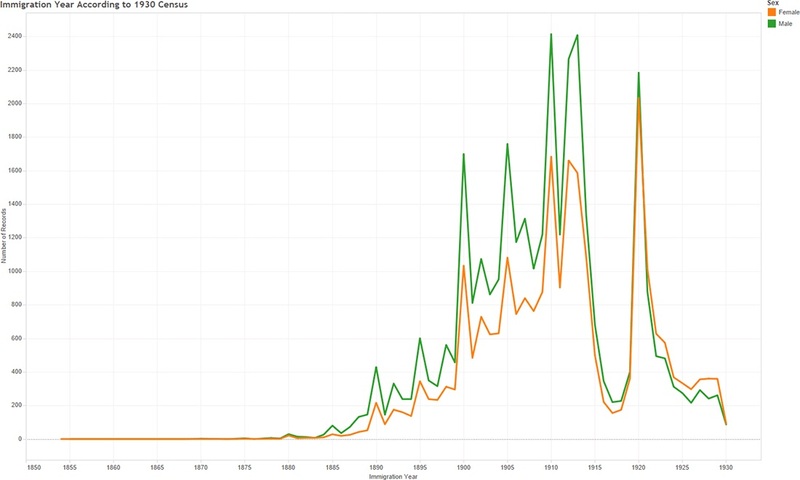

The first wave of Arab immigration to the United States began in the late 19th century. Between the 1870s and the 1930s, migrants primarily from the area formerly known as Greater Syria (a region in Southwest Asia encompassing modern day Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, and Palestine) traveled across the Atlantic to the United States.[2] As seen in Figure 1. Immigration to the states from Greater Syria steadily grew during the late 19th century, reaching its peak in the early 1910s. Following Sarah Gualtieri, I have chosen to use the term "Syrian" to refer to this group of migrants to reflect the language and categorization that is found in sources from the period. Today, many of these migrants would be considered Arab or SWANA (Southwest Asian and North African) but will henceforth mostly be referred to as Syrian.

The dominant narrative regarding the first wave of Arab migrants to the states is that they were Christian. While there does seem to be a vast number who were Christian, the first wave of immigrants to the United States were much more religiously diverse than this narrative portrays. “While we do not (and very likely can never) know the exact breakdown, there is no doubt that all immigrants included people from all three monotheistic faiths (Christian, Muslim, and Jewish).”[3]

The reasons as to why so many left Greater Syria have been debated by scholars. Traditionally, the argument has been that the World’s Fairs in Philadelphia (1876), Chicago (1893), and St. Louis (1904) functioned as a drawing force, causing migrants from Greater Syria to immigrate to the United States. This narrative depicts the United States as a beacon to which Syrian migrants were drawn to. However, as argued by scholar Sarah Gualtieri in her landmark book Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora, the influence of these fairs has been greatly exaggerated.[4] Additionally, this fails to account for the equally large group of Syrian migrants who went to other nations in the Americas, in particular Argentina and Brazil.[5] Thus, while these World Fairs may have played a role in incentivizing migrants, it was not the sole driving force. Instead, migrants emigrated for a multitude of reasons. Some emigrated to “escape a bad marriage, reunite with family, seek adventure, or flee real and perceived religious persecution.”[6] Yet in general, most seem to have left due to economic reasons. Economic changes in Greater Syria during the late 19th century facilitated and made possible transatlantic migration.[7]

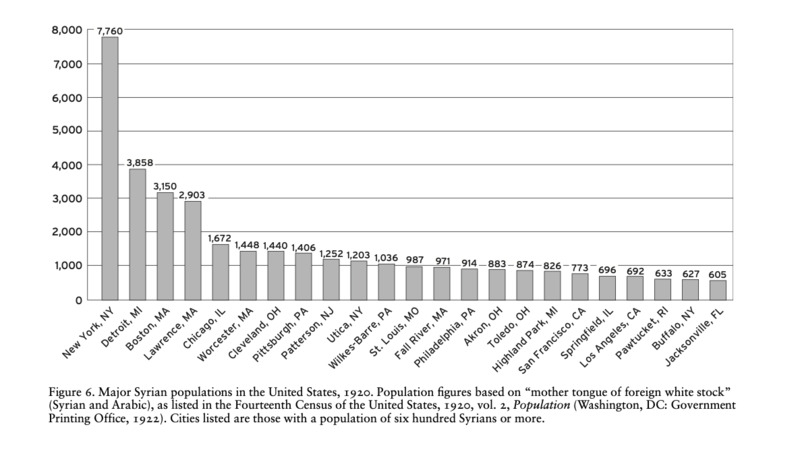

Regardless of the reasons as to why they came to the United States, Syrian immigrants quickly became part of American society. In the 1890s, most traveled to locations with demand for industrial labor, such as New York and Massachusetts.[8] In many of these states, they established distinct ethnic enclaves. As seen in Figure 2. The largest Syrian population in the United States by 1920 was in New York, but Syrian migrants traveled to various cities across the nation. As more Syrian migrants came to the United States, many began to consider acquiring American citizenship through naturalization.

Race and Naturalization Law

Beginning with the Naturalization Act of 1790, American immigration and naturalization was deeply racialized. In her article, “The Making of Modern US Citizenship and Alienage: The History of Asian Immigration, Racial Capital, and US Law”, scholar Hardeep Dhillon argues that “citizenship, as a critical feature of the US imperial project, sustained White supremacy and White purity alongside racial capital.”[9] Within this context, naturalization and citizenship was extended exclusively to “free white persons.” Following the Civil War, the naturalization law was amended to include “aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent” as eligible for citizenship. In subsequent periods, federal authorities worked to build the framework for the “modern immigration regime.”[10] This change in naturalization law allowed for non-African/European immigrants to apply for naturalization by asserting claims to African descent or whiteness. As a result, “between 1878 and 1952, US federal courts adjudicated fifty-two cases pursued by immigrants from Syria, Korea, the Philippines, China, Burma, Armenia, Japan, India, Hawai’i, and Mexico who sought to naturalize as US citizens by proving to US courts that they were indeed White.” [11]

As seen in American naturalization law, whiteness in American law functioned as a form of racial capital. Cheryl I. Harris argues that “the interaction between conceptions of race and property that played a critical role in establishing and maintaining racial and economic subordination.”[12] Whiteness thus served as a form of “property” through which one could obtain certain rights and privileges. In the case of naturalization, American citizenship functioned as a legal status affording some immigrants deemed as white with rights and privileges while restricting others from obtaining the same rights and privileges. As such, immigrants attempting to naturalize in the United States engaged in “a possessive investment in Whiteness” to prove their whiteness and obtain the rights of citizenship.[13] In the naturalization cases of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, officials, judges, and the courts created distinctions between which immigrants from Asia were white and could naturalize, and which immigrants were classified as not white.[14]

Prerequisite Cases

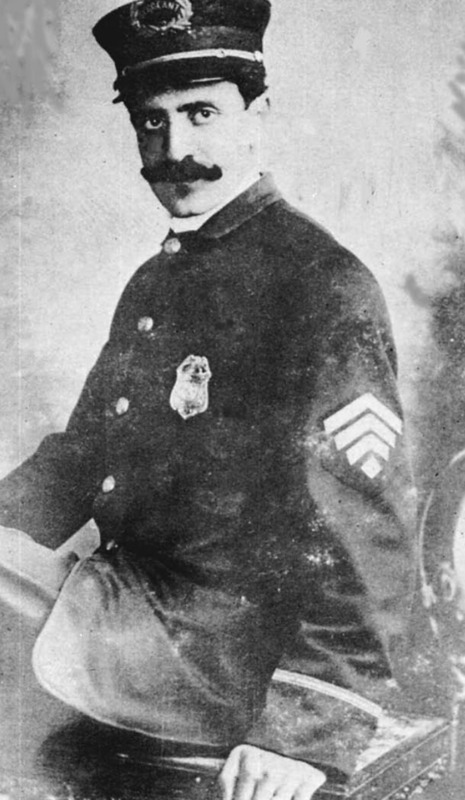

During this period, the federal courts heard a number of cases from Southwest Asian immigrants who sought to naturalize by claiming whiteness. However, the first case relating to the racialization of Syrians was not related to naturalization. In 1909 the Los Angeles Superior Court heard a case involving a man by the name of George Shishim. Shishim, a Lebanese Syrian man, had immigrated to the United States in 1894. He settled in Venice, California and became a policeman. The controversy arose in 1909, when Shishim arrested the son of a prominent lawyer accused of being a public nuisance. The accused argued that Shishim could not arrest or charge him of a crime because he was not white and therefore was not (nor could he become) an American citizen. In her analysis of the case, Gualtieri notes the similarities between the arguments of this case and the 1854 case People v. George Hall. This case, heard California Supreme Court involved a white man convicted of the murder based on the testimony of three Chinese witnesses who sought to appeal his conviction on the grounds that as non-white people, they could not legally testify against a white man in accordance with the 1850 statute which stated that “no Black, or Mulatto person, or Indian shall be allowed to give evidence in favor of, or against a White man.”[15] In People v. George Hall, the court ultimately ruled in favor of the defendant, asserting that “black” within the statute encompassed all non-white persons which included Chinese people. In Shishim’s case however, the court ruled in his favor contenting that Syrians were to be included in the term “white persons.”[16] Central to the court’s ruling was the argument presented by the defense which asserted Shishim’s connection to whiteness and Christianity through a distancing of himself from Muslims and Asians.

In 1909 in Atlanta Georgia, another case arose regarding a man named Costa Najour. Najour immigrated to the United States in 1902 and filed for naturalization in 1909 but was rejected by the federal court in Georgia. Najour appealed his case before the Fifth Circuit Court. The court ruled in his favor as well by drawing upon scientific notions of racial classification. In the case, Judge Newman distinguished between skin color and racial classification. In cases where the applicant’s qualifications were deemed sufficient then color was not of importance. However, when “personal qualifications were in doubt” then color served as a marker of ineligibility.[17] To that end, pseudo-scientific arguments of a “Caucasian race” rooted in ethnology proved to be especially appealing to judges such as Newman. Another case related to the racialization of Syrian also occurred in 1909 in Massachusetts. The In re Halladjian case involved four Armenian men who were denied naturalization. The U.S. government denied their applications on the grounds that they were of “Asiatic” origin and that “white persons” exclusively meant Europeans. The court however disagreed with this argument and granted the men citizenship, citing a long history of intermixing between the inhabitants of Europe and Asia. As such, the court dismissed the scientific argument for racial classifications and instead focused on cultural assimilability. The court highlighted the achievements of Southwest Asian and North African (SWANA) civilizations and the cultural link between SWANA people and Europeans. They also emphasized that Armenians were able to “become westernized and readily adaptable to European standards.”[18] From these three early cases, it is clear that assimilability and proximity to whiteness functioned as a key factor in determining the eligibility of naturalization applicants (see Figure 4.)

While several judges followed in the arguments of these cases, using pseudo-scientific notions of race, others rejected this notion. The most notorious dissenter was Judge Henry Smith, who dismissed the arguments as “of a strange intellectual hocus pocus.”[19] For example, in 1913 in South Carolina, Smith denied the naturalization of a man named Faras Shahid. Instead, he argued that the sole determiner of race was geographic origin. Additionally, Smith used congressional intent and what “the average citizen” in 1790 would have viewed as racial categories.[20] Thus, by 1914, when the first Dow case was brought to the court, there was a clear (albeit contradictory) legal precedent for the racialization of Southwest Asian immigrants.

[1] Akram Fouad Khater, “Arabs in America,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History (2019), 1, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199329175.013.600.

[2] Sarah Gualtieri, Between Arab and White: Race and Ethnicity in the Early Syrian American Diaspora (University of California Press, 2009), http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/reed/detail.action?docID=837328; Khater, “Arabs in America.”

[3] Khater, “Arabs in America,” 4.

[4] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 37.

[5] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 37.

[6] Khater, “Arabs in America,” 2.

[7] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 50.

[8] Khater, “Arabs in America,” 6.

[9] Hardeep Dhillon, “The Making of Modern US Citizenship and Alienage: The History of Asian Immigration, Racial Capital, and US Law,” Law and History Review 41, no. 1 (2023): 9, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0738248023000019.

[10] Dhillon, “The Making of Modern US Citizenship and Alienage,” 2; Kelly Lytle Hernandez, “The Whites-Only Immigration Regime,” Western Historical Quarterly 56, no. 1 (2025): 1, https://doi.org/10.1093/whq/whae078.

[11] Dhillon, “The Making of Modern US Citizenship and Alienage,” 2.

[12] Dhillon, “The Making of Modern US Citizenship and Alienage,” 6.

[13] Dhillon, “The Making of Modern US Citizenship and Alienage,” 5.

[14] Dhillon, “The Making of Modern US Citizenship and Alienage,” 6.

[15] Claire Jean Kim, Asian Americans in an Anti-Black World, 1st ed. (Cambridge University Press, 2023), 51, https://doi.org/10.1017/9781009222280; Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 58.

[16] Hadi Khoshneviss, “Accruing Whiteness: Power and Resistance in Prerequisite Citizenship Cases of Immigrants from the ‘Middle East,’” Citizenship Studies 25, no. 5 (2021): 624, https://doi.org/10.1080/13621025.2021.1923658.

[17] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 60.

[18] John Tehranian, Whitewashed: America’s Invisible Middle Eastern Minority, Critical America (University Press, 2009), 51.

[19] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 61.

[20] Khoshneviss, “Accruing Whiteness,” 628.