The Cases

Who Was George Dow?

George Dow was a Christian Syrian man born in 1862 in Batroun, Syria (part of modern-day Lebanon). In 1889, at the age of 27, he immigrated to the United States, entering through the port of Philadelphia. From Philadelphia, he made his way to Evansville, Indiana, and finally to Summerton, South Carolina, where he ran a store with his wife Saydy.[1] Very little else is known about Dow, and there exist no publicly available photos of him or his family.

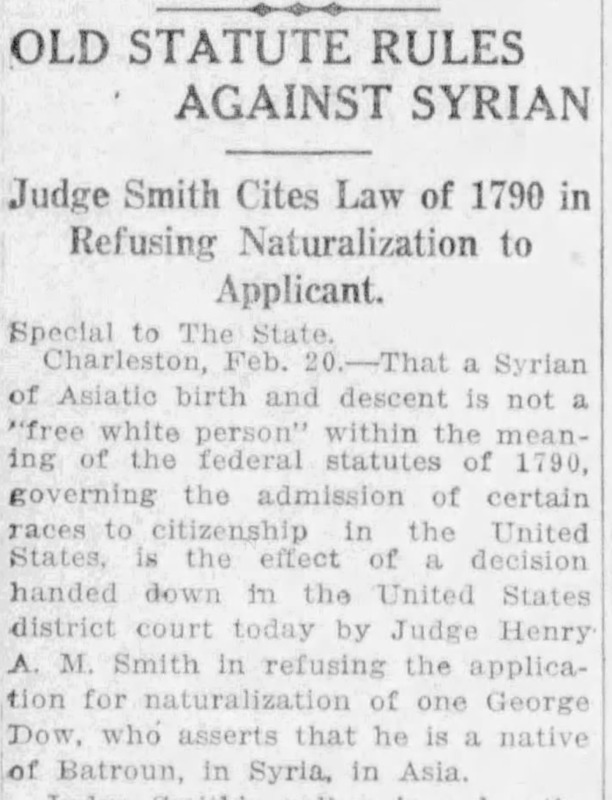

Ex Parte Dow (1914)

In 1913, Dow submitted a petition to naturalize as an American citizen. His petition would spark a tense legal battle regarding the racial status of Syrians. In 1914, Dow testified before the court, led by Judge Henry Smith (the same Judge who ruled in Faras Shahid’s case). As noted by Gualtieri, when brought to testify before the court, it became apparent that Dow was unfamiliar with the American system of government and was lacking in English language skills. “To questions posed to him about U.S. politics, for example, he responded that there were about thirty houses of Congress and that the difference between the government in Turkey and the United States was that he would like to be a citizen of the United States.”[2] The lawyer appointed by the federal government found Dow’s lack of language proficiency and knowledge to be sufficient cause for the denial of his naturalization application. Yet, it was not on the grounds of his knowledge (or lack thereof) that he was denied naturalization. Instead, Judge Smith ruled against his petition on the basis that Dow did not meet the race requirement as he was neither of African descent nor a “free white person.” In the opinion of the court, Smith again framed his argument based on geography. He argued that Dow was “not that particular free white person to whom the act of Congress has donated the privilege of citizenship in this country with its accompanying duties and responsibilities” and that by “free white persons” Congress had meant to “restrict the privilege as extended to such foreigners to persons of European habitancy and European descent.”[3] Thus, Dow, being born in Greater Syria, was “Asiatic” and not eligible for naturalization.

In re Dow (1914)

Following the refusal of his petition, Dow was granted a rehearing. Again, Dow brought his case before Judge Smith, now with the assistance of the Syrian American Association (SAA). He presented a complex defense of Syrian whiteness. His defense utilized the rationales presented in previous attempts to affirm Syrian whiteness. According to the opinion of the court (language replicated below), Dow’s argument hit on five key points:

- That the term “white persons” in the statute means persons of the “Caucasian race,” and persons white in color.

- That he is a Semite or a member of one of the Semitic nations.

- That the Semitic nations are all members of the “Caucasian” or white race.

- That the matter has been settled in their favor as the European Jews have been admitted without question since the passage of the statute and that the Jews are one of the Semitic peoples.

- That the history and position of the Syrians, their connection through all time with the peoples to whom the Jewish and Christian peoples owe their religion, make it inconceivable that the statute could have intended to exclude them.[4]

On the first three points, while these arguments had in the past worked, Smith was firm in his dismissal of the argument, again relying on congressional intent and what the framers of the statute in 1790 would have considered “white persons” which “to the average citizen of the United States in 1790, would seem to have meant Europeans.”[5] In the fourth point, Dow utilized legal precedent. He argued that European Jews who were also Semitic had been allowed to naturalize as white persons, and thus Syrians (also being Semitic) should be able to naturalize. To this point, however, Smith emphasized geographic origin yet again. The European Jew, he argued, had become “racially, physiologically, and psychologically a part of the peoples he lives among” and was thus ostensibly European first and foremost.[6] As to the final point, Dow’s defense drew on a cultural argument by citing the history and position of Syrians as grounds for their naturalization. Unfortunately for Dow, none of these arguments persuaded Smith, and Dow was once again denied citizenship.

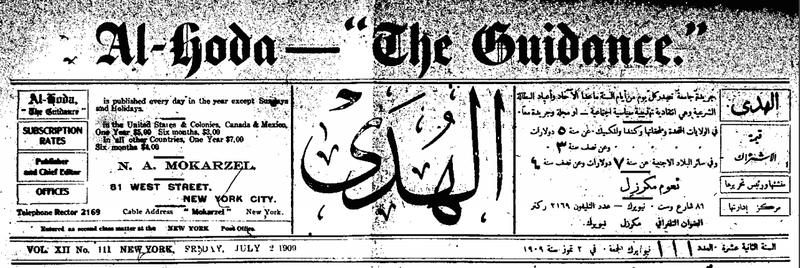

What is noteworthy about this case is not simply the arguments that were made but how the case was framed in the opinion of the court. Smith opened the case by stating that “deep feeling has been manifested on the part of the Syrian immigrants because of what has been termed by them the humiliation inflicted upon, and mortification suffered by, Syrians in America by the previous decree.”[7] Smith then goes on to clarify that “the true ground of this supposed humiliation is that the applicant and his associates conceive the refusal of this privilege to mean that they do not belong to a white race but to a colored and what they consider an inferior race.”[8] Gualtieri argues that these remarks by Smith were not without their merits and that many Syrians did view their exclusion from naturalization as an insult.[9] This is reflected in the arguments that were put forth by Syrians in naturalization cases. The Dow case had been publicized in both English and Arabic language papers. For instance, the Syrian Society for National Defense (SSND) published updates on the case in the popular Arabic-language paper al-Hoda. As seen earlier, in many of the earlier naturalization cases (as well as Dow’s), their inclusion in the “white race” was predicated on their perceived assimilability, connection to the Western world, and Christian background. Yet, as the refusal to naturalize Syrian immigrants rose, some began to shift their approach to claim whiteness. Thus, Syrian applicants forewent these arguments and instead resorted to anti-black and anti-Asian sentiments. Through adopting white-supremacist rhetoric, they sought to define their whiteness through their perceived difference from Asian and Black people.[10] For example, SSND secretary Najib al-Sarghani, who was responsible for publicizing the case in al-Hoda, wrote that the ruling in Dow placed Syrians as “no better than blacks [alzunuj] and Mongolians [al-mughuli]. Rather, blacks will have rights [to vote, for example] that the Syrian does not have.”[11]

Dow v. United States (1915)

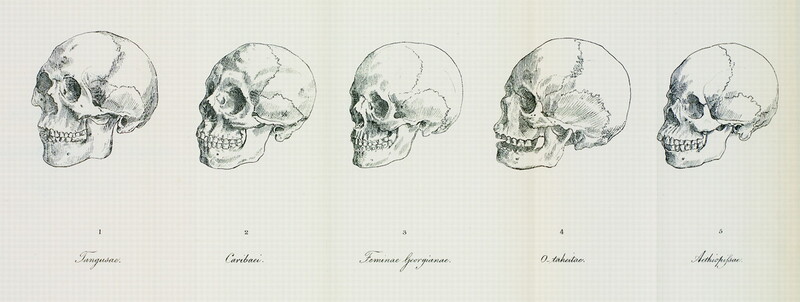

In 1915, Dow was granted another chance to appeal his case to the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit. This time, the case was presided over by Judge Charles Albert Woods. Woods approached the subject matter quite differently from Smith, affirming that Syrians were indeed “white persons.” Woods began by pushing back on some of the earlier arguments of Syrians regarding the conflation of the term Caucasian and whiteness. To make this argument, Woods drew on ethnology and the work of Johann Friedrich Blumenbach. Blumenbach’s racial classification (see figure), published in 1781, classed many groups from Southwest Asia, such as Syrians, as “Caucasian.” Blumenbach’s work would not have been known to the congress at the time. As such, at the time of the initial statute, it is likely that “white persons” referred exclusively to Europeans. However, while Smith relied on congressional intent and “common knowledge” as it related to the initial statute, Woods argued that the original 1790 act had been repealed and amended multiple times already, and instead the court should rely on congressional understanding at the time of the last amendment.

“Certainly it cannot be said that, after all this legislative discussion and reconsideration and enactment, the present statute must be construed in the light of the knowledge and conception of the legislators who passed the original statute in 1790, without respect to the more definite and general knowledge and conception which must be attributed to the legislators who, upon reconsideration of the whole subject, enacted subsequent statutes including that now in force.”[12]

As such, the court should rely on common understandings of race in 1875 when the act had last been modified. At this date, Wood argued, “it seems to be true beyond question that the opinion generally received was that the inhabitants of a portion Asia were classed as white.”[13] Woods acknowledged that Syrians “have racial decent from many different sources” however he remained firm in his assertion that what mattered was that in 1875, most would have agreed that Syrians were white. “the consensus of opinion at the time of the enactment of the statute now in force was that they were so closely related to their neighbors on the European side of the Mediterranean that they should be classed as white, they must be held to fall within the term ‘white persons’ used in the statute.”[14] Woods thus ruled that the act was being given a more liberal interpretation “so as to include within the term ‘white persons’ Syrians, Armenians, and Parsees.”[15] With this decision, Dow finally secured American citizenship, and Syrians had, for the time being, secured their whiteness.

[1] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 66.

[2] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 67.

[3] Ex Parte Dow, 211 F. 486 (District Court, E.D. South Carolina 1914), https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/8806875/ex-parte-dow/.

[4] In Re Dow, 213 F. 355 (District Court, E.D. South Carolina 1914), at 357, https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/8807595/in-re-dow/.

[5] In re Dow, 366.

[6] In re Dow.

[7] In re Dow.

[8] In re Dow.

[9] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 69.

[10] Khoshneviss, “Accruing Whiteness,” 629.

[11] Gualtieri, Between Arab and White, 72.

[12]Dow v. United States, 226 F. 145 (Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit 1915), https://www.courtlistener.com/opinion/8812549/dow-v-united-states/.

[13] Dow v. United States.

[14] Dow v. United States.

[15] Dow v. United States.