Stagnation 1976- ~1985

The death of Mao Zedong and the arrest of the Gang of Four in 1976 brought an end to the Cultural Revolution which had ravaged Shanghai for approximately a decade. Virtually no improvements to living standards had been made in the past thirty years. However, rather than making plans to renew the ailing city, the Chinese central government instead focused on rooting out any supporters of the Gang of Four who persisted in Shanghai's government. This led to Shanghai having little representation at the national level. As a consequence, Shanghai was largely excluded from the benefits of the first round of economic reforms that the CCP initiated in 1978. Shanghai was left out of a handpicked group of Chinese cities that would be permitted to become "special economic zones." Although small reforms were made, such as allowing the sale of low-valued property and allowing tenants to build new structures to improve their homes in 1981 and 1982, respectively, they did little to help. For the first time in over a hundred years, Shanghai risked losing its preeminence among China's cities. To make matters worse, since 1949 Shanghai had been forced to contribute more than 87 percent of its total revenue to the central government, a state of affairs in which the city languished until the mid 1980s.

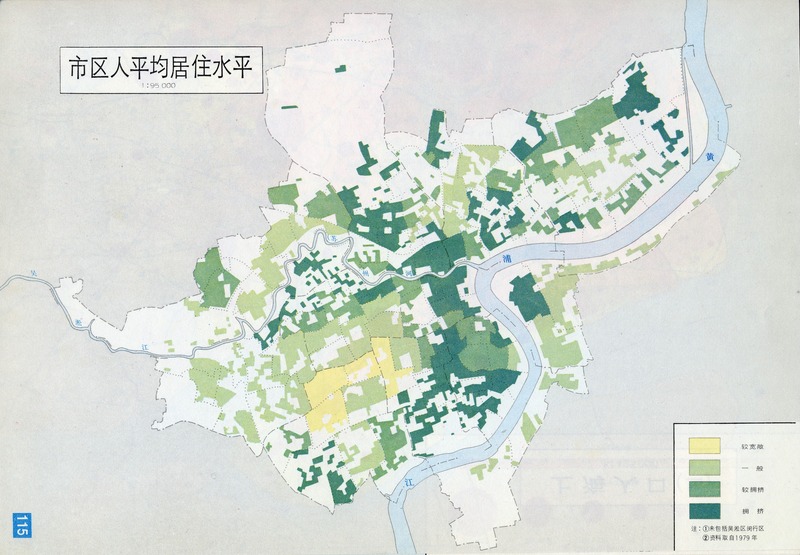

Average Residential Space Per Person in Shanghai Urban Area

Key:

Yellow- Fairly large

Light Green- Regular

Green- Rather crowded

Dark Green- Crowded

The map reveals how crowded the urban area of Shanghai had become after decades of neglect and decay. On average, every resident of Shanghai had a little less than 5 square meters of space in 1982.

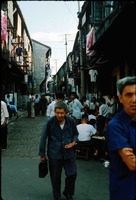

This image depicts a typical moment in urban life in Shanghai during its long period of stagnation in the early 1980s. Before the 2000s, the majority of Shanghai's residents lived in closely packed row houses like those pictured. Such houses are called Lilong. A single home most often housed multiple families. The narrow lanes and alleyways between lilong permitted very little privacy and so produced tightly knit communities. The pervasive lack of available space meant that these alleyways doubled as communal spaces for cooking, washing, and socializing. As Shanghai's population has ballooned in recent decades, many lilong, themselves originally constructed to reduce the overcrowding caused by an influx of migrants in the 1800s, have been demolished in order to build even higher-density housing.