The Ruling

The Citizenship Clause Debate

A crucial component of the debate in United States v. Wong Kim Ark was the scope of the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” in the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Under this provision, all persons born or naturalized in the United States and subject to U.S. law are citizens (Berger 1188). However, since the clause was initially included to allow birthright citizenship for Blacks in addition to Whites, it was unclear whether it applied to ethnic minorities (Koh 472). Wong argued that because he was born in San Francisco, he was subject to the jurisdiction of the United States and, therefore, was a citizen. As such, he would be exempt from the exclusion laws—rendering his detainment in the Port of San Francisco unlawful (Thomas 696-697; Wong Kim Ark 649-653). By contrast, the government claimed that birth in the United States did not automatically grant an individual citizenship. Rather, it argued that because Wong’s parents were “Chinese persons and subjects of the Emperor of China,” Wong inherited this status and was also a “Chinese person and subject of the Emperor of China.” The government further reasoned that “Wong Kim Ark has been at all times, by reason of his race, language, color and dress, a Chinese person” and was not an American citizen (Wong Kim Ark 650). If Wong were not a U.S. citizen, he would be legally barred from entering the country under the Chinese Exclusion Act. By emphasizing that Wong and his parents were “Chinese persons” and not American citizens, the government highlighted the racialized conception of birthright citizenship that underpinned its argument. Likewise, these statements conflated “Chinese” with otherness, suggesting that “Chinese” and “American” were at odds with each other (Lee 105). The government’s framing of the issue in United States v. Wong Kim Ark elucidates the prominent role racial animus played in the circumstances surrounding the case, implying that Chinese persons’ racial difference was reason enough to justify their exclusion.

Majority Opinion

Justice Gray wrote the majority opinion, backed by Justices Brown, Shiras, White, and Peckham (Woodworth 556). Gray argued that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth Amendment both reaffirmed citizenship by birth in the United States “in the most explicit and comprehensive terms” (Wong Kim Ark 675). The court asserted that Amendment’s “opening words, ‘All persons born,’ are general, not to say universal, restricted only by place and jurisdiction, and not by color or race” (676). Under this interpretation, Wong was a citizen and could not be denied re-entry or excluded under the Chinese Exclusion Act. Two factors were crucial to the justification of the majority opinion: English common law and European immigration.

In response to the Constitution’s failure to define “citizen of the United States” and “natural-born citizen of the United States,” Gray contended that the court must turn to English common law as a result, which adhered to the principle of jus soli (citizenship by birth). Under this system, all persons born under the jurisdiction of the King were his subjects (“Jus Soli Law and Legal Definition”; Wong Kim Ark 653-655). Gray argued that the United States adopted this common law principle and its exceptions. He maintained that the phrase “subject to the jurisdiction thereof” sought to exclude the same groups exempt from birthright citizenship under English common law: “children born of alien enemies in hostile occupation, and children of diplomatic representatives of a foreign State.” The phrase also excluded children of Native American tribes (Thomas 697; Wong Kim Ark 682). Those excluded under these exemptions “were not subject to the full range of civil and legal sanctions that could be imposed on all other residents.” By contrast, Gray reasoned that even if Wong’s parents were Chinese subjects, Wong was nevertheless subject to the same laws or “jurisdiction” as any other U.S. resident (Frost 61). Rooting its justification in historical precedent, the court concluded that “the [Fourteenth] Amendment, in clear words and in manifest intent, includes the children born, within the territory of the United States, of all other persons, of whatever race or color, domiciled within the United States” (Wong Kim Ark 693). It is noteworthy that explicit concerns about racial inclusion were not used as a basis for the court’s ruling. In fact, the majority of the argument is overwhelmingly race-neutral. The court did, however, briefly touch on immigration and race-based naturalization laws in effect at the time and the case Yick Wo v. Hopkins, which ruled that the equal protection clause extended to Chinese persons. Nonetheless, its discussion of common law and the Fourteenth Amendment, which takes up most of the opinion, makes little mention of race. Even when explaining that citizenship applied to all persons regardless of color or race, the court spoke of race generally, avoiding overt claims about the racial equality of Chinese persons (Koh 472-474). As scholar Jennifer Koh observed, “the majority stop[ped] short of asserting that Chinese individuals have full membership claims or adopting racial equality as a basis for the decision” (473). Instead, the court rooted its opinion in historical precedent, contending that “the common law precedent of birthright citizenship [was] too well-rooted to abandon at that point of the nation’s history” (Salyer 75).

“To hold that the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution excludes from citizenship the children, born in the United States, of citizens or subjects of other countries, would be to deny citizenship to thousands of persons of English, Scotch, Irish, German or other European parentage, who have always been considered and treated as citizens of the United States” (Wong Kim Ark 694)

To the extent that the court’s ruling invoked concerns about race, it did so primarily out of concern for the threat denying Wong’s citizenship would pose to native-born White children of European immigrants. As Gray’s comments in the above quote illustrate, up to that point in U.S. history, recognition of birthright citizenship had been inherently racialized. While the children of White immigrants had “always been considered and treated as citizens,” recognition of citizenship for native-born Chinese Americans—who existed beyond the confines of the Black and White racial paradigm American society had assigned to citizenship—was inconsistent and unreliable (Wong Kim Ark 694). Gray argued that if the court ruled against Wong, it could undermine the citizenship of thousands of children of White immigrants commonly perceived to be U.S. citizens. In fact, this was an underestimate. In 1900, fifteen million of the United States’ native-born White population had foreign-born parents—almost a quarter of the country’s native-born White population (Berger 1249). By contrast, 11% of America’s Chinese population, or about 9,885 people, claimed to be born in the United States (United States, Department of Commerce 23).

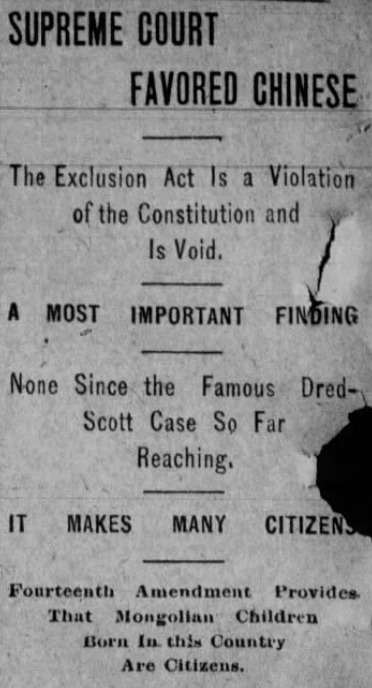

Gray’s scant references to race and statements about the children of European immigrants suggest that the court’s decision was not motivated by a desire to make citizenship more inclusive on the basis of race but rather to prevent the exclusion of people perceived to be White. Taking into consideration the demographics of native-born citizens, the Supreme Court’s decision can be seen as more of a cost-benefit analysis than an acknowledgment of Chinese persons’ racial equality. Anti-Chinese legislation like the Page Act severely restricted the immigration of Chinese women and, in turn, kept the number of native-born Chinese Americans relatively low. Consequently, recognizing Wong’s citizenship would only offer the possibility of citizenship to a small percentage of Chinese Americans, while ruling against Wong had the potential to invalidate a quarter of the nation’s citizens—a risk that the majority of the court was unwilling to take. The Supreme Court ultimately ruled that Wong Kim Ark, by reason of having been born in the United States to parents that “have a permanent domicil and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China,” was a U.S. citizen (Wong Kim Ark 705). Regardless of the reasoning behind the decision, it nonetheless set a significant precedent that denied racially determined birthright citizenship (except in the case of Native Americans) and continues to confer citizenship today.

Dissenting Opinion

Justice Fuller wrote the dissenting opinion, joined by Justice Harlan. Justice McKenna did not take part in the case (Wong Kim Ark 732). The dissent took concern with the majority’s reliance on common law, arguing that birthright citizenship was a result of feudalism and should not be considered in interpretations of American law (Thomas 699; Wong Kim Ark 707-710). Fuller argued for upholding citizenship by descent based on an interpretation of the phrase “that all persons born in the United States and not subject to any foreign power” in the Civil Rights Bill of 1866. He contended that this indicated people could be born in U.S. territory and, by inheritance through their parents, still be subjects of the political jurisdiction of a foreign power, which would undermine their claim to birthright citizenship in the U.S. (Thomas 700; Wong Kim Ark 719-720). Despite Fuller’s argument, the six-justice majority ruled that Wong was a citizen, forever changing the landscape of birthright citizenship in the United States.