Impact

Today, the United States recognizes citizenship through birthright or inheritance from one’s parents (United States, Department of State Foreign Affairs). The ruling in United States v. Wong Kim Ark set a precedent for birthright citizenship in the United States that is still in effect today. It has been cited in several Supreme Court cases related to the citizenship of people of Chinese and Japanese descent, including Weedin v. Chin Bow (1927), Morrison v. California (1934), and Nishikawa v. Dulles (1958). Although it was a significant step forward for the equality of Chinese Americans, the ruling only had a limited impact on the potential for Chinese persons to become citizens, who continued to face “race-based bars to naturalization” until Congress repealed the Chinese Exclusion Act and extended the right to naturalization to Chinese persons in 1943 (Koh 476; Salyer 58). It also led to new obstacles in proving citizenship. In the years following the verdict, immigration officials continued to undermine Chinese birthright citizenship. Despite the ruling in Wong’s favor, people of Chinese descent continued to face considerable Sinophobia and legal resistance to their right to reside in the United States—including Wong Kim Ark himself.

Wong's Family

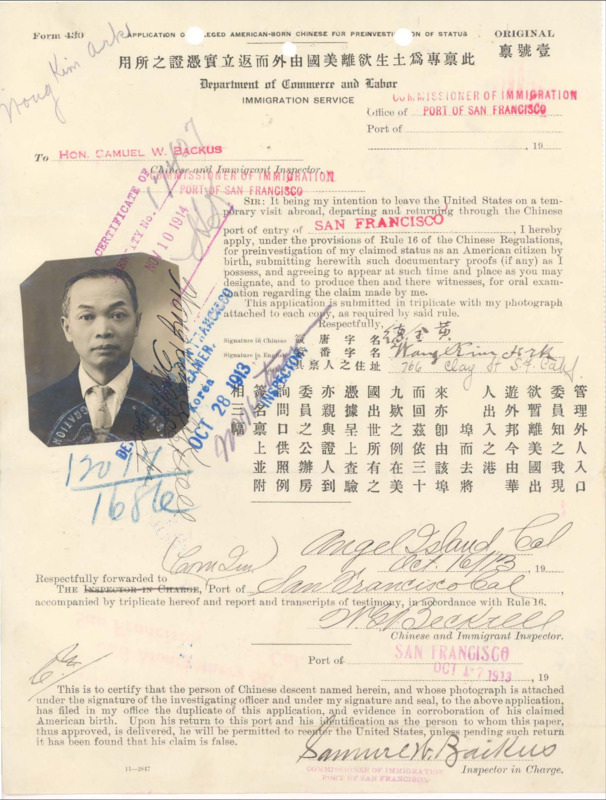

The remainder of Wong Kim Ark’s life highlights the significance and shortcomings of the Supreme Court’s ruling. Although he was a U.S. citizen in theory, his citizenship continued to be called into question. However, his judicial victory nonetheless made it possible for foreign-born children of native-born Chinese citizens, including his own sons, to immigrate to the U.S. and claim citizenship—claims that were often rejected by immigration officials. In October 1901, Wong was arrested in El Paso, Texas, “on the ground that he was a ‘Chinese person’ who did ‘unlawfully, fraudulently, and knowingly enter and . . . remain in the United States of America in violation of the Chinese Exclusion Acts.’” He was released on a $300 bail. Despite being the plaintiff in a Supreme Court case that affirmed birthright citizenship, Wong would not have his citizenship confirmed until February 18, 1902, when U.S. Commissioner Walter D. Howard asserted that Wong was a citizen and had a right to remain in the United States (Frost 66). After being released, Wong would take at least three more trips to China in 1905, 1914, and the early 1930s. His wife, who remained in China, gave birth to two more sons after Wong’s 1905 and 1914 trips (Berger 1228; Koh 477; Frost 65-68). Between 1910-1926, Wong’s four sons, all of whom were born in China, immigrated to the United States “under the rule that marital children of resident U.S. citizens wherever born were eligible for citizenship” (Berger 1253). His eldest son was denied entry in 1910 and was eventually deported to China on January 9, 1911 (Frost 66-68). In 1924, Wong’s third son immigrated to the United States and was detained by immigration officials. He won his case on appeal and was allowed into the U.S. as a citizen. In March 1925, Wong’s second son immigrated to the U.S. and was admitted as a citizen. His youngest son came to the United States soon after (68-69). However, only Wong’s youngest son would take up permanent residence in the United States. He would go on to serve in World War II, making a career with the Merchant Marines. A few years prior to the outbreak of the war, Wong moved to China at age 62, where he remained until his death, sometime during or shortly after WWII (Berger 1255).

Wong’s experiences exemplify what scholar Claire Jean Kim has termed the “civic ostracism” of Asian Americans, the process by which Whites construct Asian Americans as culturally foreign and unassimilable “in order to ostracize them from the body politic and civic membership” (107). The disconnect between the Supreme Court’s ruling and on-the-ground enforcement of the law enabled Whites to deny Wong inclusion in American society. Although he was a Chinese American, in the eyes of the El Paso immigration officials, he was an “immutably foreign” Chinese person who was in violation of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Similarly, although Wong’s children should have theoretically been granted citizenship, the lack of court-sanctioned standards for how citizenship would be determined led immigration officials to enact their own standards of measuring citizenship, through which they continued to ostracize Wong and deny his family’s citizenship on arbitrary grounds (Lee 105-106). Although United States v. Wong Kim Ark was a significant step forward for the inclusion of Chinese Americans, they nonetheless continued to be seen as culturally “other” and “unfit for . . . the American way of life” (Kim 112).

Government Attempts to Undermine Birthright Citizenship

In the wake of the United States v. Wong Kim Ark ruling, some government officials ignored the decision, offering their own interpretations of birthright citizenship, while others found ways to make birthright citizenship near inaccessible. For example, in 1904, American-born Yee Ching Ton was denied re-entry to the United States by Victor H. Metcalfe, the Secretary of the Department of Commerce and Labor. Yee had spent most of his life in China but was born in the United States, which he had Caucasian witnesses confirm to immigration officials (Frost 63). Issuing his own interpretation of the Supreme Court ruling, despite an overwhelming lack of legal precedent, Metcalfe denied Yee’s birthright citizenship, stating that “such a case . . . when the child born in the United States waits until he is 26 years of age, establishes himself in his own country and marries before he attempts to claim his birthright, is not within the reasoning upon which the Supreme Court reached its ruling in the Wong Kim Ark case” (“Decision Makes a Precedent”). The government continued to undermine birthright citizenship by requiring a near-impossible standard of proof. It began operating with the assumption that Chinese persons were excludable unless they could prove their citizenship. This was an arduous process that required two White witnesses who could affirm an individual was born in the U.S., ridiculous questions that asked a returning citizen about things like “the number of steps or rooms in the house in which he had been born, even if he had not lived in it for years,” and lengthy interrogations followed by intrusive physical exams (Frost 63-64).

Birthright citizenship is still a contentious topic to this day. Although “the parameters of the jus soli principle [birthright citizenship], as stated by the court in Wong Kim Ark, have never been seriously questioned by the Supreme Court, and have been accepted as dogma by the lower courts,” birthright citizenship has come under scrutiny from politicians for decades, notably Donald Trump (Glen 80). In 2019, Trump made statements that alarmingly resembled the claims made by the U.S. Government against Wong Kim Ark, stating: “We’re looking at that very seriously, birthright citizenship, where you have a baby on our land, you walk over the border, have a baby - congratulations, the baby is now a U.S. citizen . . . It’s frankly ridiculous” (Reuters Staff). Over one hundred and twenty years after the ruling in United States v. Wong Kim Ark, baseless, racist accusations continue to plague discussions of immigration and birthright citizenship in the United States.

Although birthright citizenship continues to face opposition, United States v. Wong Kim Ark nonetheless played a critical role in shaping United States citizenship. Scholar Gary Jacobsohn aptly summarized the impact of the decision: “Henceforward the ability of the native-born to share in the aspirational content of American national identity was formed only by one’s relation to the physical boundaries of the United States” (Jacobsohn 92; Thomas 706). That is, it asserted that Chinese Americans had the same right to birthright citizenship that Justice Gray stated had “always been considered” to apply to the children of European immigrants—albeit more in theory than in practice in the years following the decision. United States v. Wong Kim Ark did not overturn the Chinese Exclusion Acts, nor did it make the process of proving birthright citizenship reasonable or equitable. Nevertheless, it provided the possibility of birthright citizenship to a small number of people of Chinese descent (and other racial minorities) and, in doing so, began deconstructing barriers to equality for Asian Americans.