Historical Context: Citizenship & Chinese Immigration

To understand the significance of United States v. Wong Kim Ark, it is important to understand the historical and legal issues that gave rise to the case. Wong Kim Ark’s case came about during a period rich with xenophobia, racism, and anti-Chinese prejudice. Legislation was passed at the state and federal levels to reduce Chinese immigration and restrict the rights of Chinese persons living in the United States. Particularly salient for the case of United States v. Wong Kim Ark are the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 & the Fourteenth Amendment

The primary question in United States v. Wong Kim Ark was whether American-born people of Chinese descent were included in the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, as is explained on the following page. In issuing its opinion on the case, the Supreme Court examined the circumstances that led to the adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, particularly the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (Long). Passed by the same Congress that ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, the act sought to integrate Blacks into American society in the wake of the U.S. Civil War (“Historical Highlights”; Thomas 700). The Civil Rights Bill of 1866 declared that, regardless of color, race, or “previous condition of slavery or involuntary servitude,” “all persons born in the United States,” except Native Americans, were “hereby declared to be citizens of the United States” (“Historical Highlights”). As detailed in the above quote, the act also outlined the rights of American citizenship, asserting that all citizens have equal benefits and protection by the laws. However, it did not discuss political rights such as the right to hold public office or vote (Kendi). The bill was initially vetoed by President Andrew Johnson, but the 39th Congress overrode the veto on April 9, 1866. Elements of the bill were later constitutionalized in the Fourteenth Amendment so that it would be “safe from presidential interference and shifting congressional majorities” (“Civil Rights Act of 1866”; Foner 68).

The Fourteenth Amendment was ratified on July 9, 1868 (“History of Law”). In what is referred to as the Citizenship Clause, the Fourteenth Amendment granted citizenship to “all persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof,” including people who were formerly enslaved. It also granted all citizens “equal protection of the laws” (“14th Amendment”). The Citizenship Clause is seen by many scholars as a reaction to Justice Taney’s 1858 ruling in Dred Scott v. Sandford, which denied citizenship to Blacks, free or enslaved, and effectively made citizenship available only to Whites (Koh 472; Thomas 695-696). A few years later, the Naturalization Act of 1870 expanded upon the original language outlined in 1790, which applied to “any alien, being a free white person,” to include “aliens being free white persons, and to aliens of African nativity and to persons of African descent” (“Nationality Act of 1790”; Smith). However, it did not include those of Asian descent in the right to naturalization, and neither these acts nor the Citizenship Clause resolved the issue of birthright citizenship for people who were neither Black nor White.

Anti-Chinese Violence & the Chinese Exclusion Act

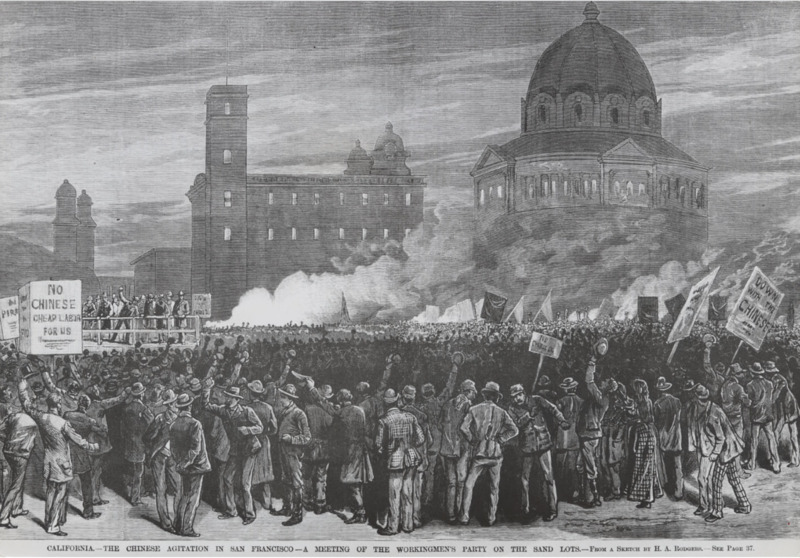

The latter half of the nineteenth century saw considerable racism and violence against Chinese Americans. On July 23, 1877, a mob of people who had recently lost their jobs due to the economic depression marched to the Chinatown area of San Francisco, beginning a three-day pogrom that would come to be known as the San Francisco riot of 1877. Rallying around cries that “The Chinese must go,” the mob attacked dozens of Chinese homes, laundries, and other businesses (Brekke). According to the New York Times, the mob had “resolved to exterminate every Mongolian and wipe out the hated race” (“The Force of ‘Sympathy’”). By the end of the riots, four Chinese men were dead; one was shot and burned to death after the mob set his home ablaze (Frost 45).

A reflection of the period’s anti-Chinese prejudice, the Chinese Exclusion Act was passed in 1882, severely restricting Chinese immigration. The act placed a ten-year immigration ban on Chinese laborers coming to the United States and required that Chinese people living in the U.S. obtain a certification to be allowed re-entry after leaving the country. The act also asserted that “state and federal courts could not grant citizenship to Chinese resident aliens, although these courts could still deport them” (“Chinese Exclusion Act”). The Chinese Exclusion Act expanded upon previous anti-Chinese legislation like the Page Act of 1875. The Page Act technically prohibited “the importation of unfree laborers and women brought for lewd and immoral purposes” from “China, Japan, or any Oriental country,” but “its unspoken focus was on Chinese women” (Hijar; “Page Law”). As scholar Maddalena Marinari explains, “the Page Act proved an effective way to restrict admission of Chinese women and thereby control local Chinese communities by skewing sex ratios and preventing Chinese American men from having children in the United States” (274).

In 1888, the Scott Act expanded upon the Chinese Exclusion Act, eliminating one of the act’s formerly exempt statuses, Chinese laborers returning to the U.S. The act left 20,000 Chinese workers who had obtained “Certificates of Return” trapped outside the U.S. (“Scott Act of 1888”). When the exclusion act’s ten-year ban expired in 1892, it was extended by the Geary Act, which mandated that Chinese residents obtain a certificate of residence to prove they entered the U.S. legally. If they failed to do so, they faced deportation, as did Chinese individuals found “unlawfully” working in the country (“Geary Act”). In 1902, the Chinese Exclusion Act was extended for another ten years. It was later made permanent by Congress in 1904. The Chinese Exclusion Act remained in effect until it was repealed by Congress in 1943 (“Chinese Exclusion Act”; “Extension of the Chinese Exclusion Act”). At the time of Wong Kim Ark’s detainment in 1895, Collector of Customs John H. Wise barred him from re-entry and detained him under the provisions of the exclusion laws (Lee 103). As is discussed in the following two pages, this would give rise to the core issue in the case: Wong’s citizenship. If Wong were a citizen, he would be exempt from the Chinese Exclusion Act. If he were not, the denial of his re-entry would be justified.