Case Facts

The story of Wong Kim Ark illuminates the ways citizenship was used as a tool of racial exclusion against Chinese people in the nineteenth-century United States, as well as their resourceful use of the law to combat the systems of racial oppression wielded against them. Wong Kim Ark was born in San Francisco in either 1870 or 1873. 1873 is the year reported in the Supreme Court case; however, 1870 is the year reported in the writ of habeas corpus filed on behalf of Wong Kim Ark in October 1895 (Application of Wong Kim Ark; United States v. Wong Kim Ark 649). His parents were Chinese citizens with a permanent domicile in the United States at the time of his birth. During their time in San Francisco, Wong’s family lived in the center of Chinatown on the second floor of 751 Sacramento Street, above a grocery store his father co-owned (Frost 39). Wong’s parents remained in the United States for 20 years before returning to China between 1889 and 1890. Wong Kim Ark stayed behind in San Francisco, where he worked as a cook (Berger 1227-1228; Wong Kim Ark 649-651).

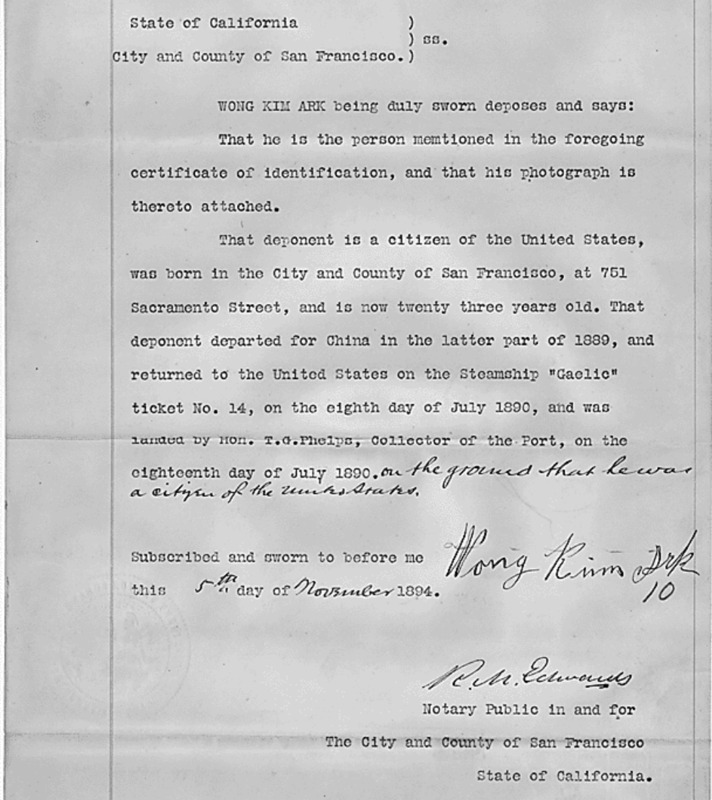

Sometime between 1889 to 1890, Wong Kim Ark took a trip to China to visit his parent’s village of Ong Sing. During this trip, he married a woman from a nearby village named Yee Shee. Soon after Wong returned to America, Yee Shee gave birth to his eldest son in China. Wong was allowed re-entry to the United States as a citizen on July 26, 1890, by Collector of Customs Timothy Phelps. In 1894, at age 21, Wong Kim Ark took another trip to China to visit his parents, where he met his eldest son for the first time. Yee Shee later gave birth to Wong’s second son in 1895 (Berger 1228; Frost 47; Lee 103). When Wong tried to return to the United States in August 1895, he was denied re-entry by the “notoriously anti-Chinese” Collector of Customs John H. Wise and detained at the Port of San Francisco. Wise argued that Wong was not a U.S. citizen even though he was born in the United States and, therefore, was subject to exclusion under the Chinese Exclusion Act (Lee 103-104). He remained in custody for five months on a steamship while his case was being tried (Berger 1230).

With the help of a mutual aid society known as the Chinese Six Companies, Wong hired notable San Francisco attorney Thomas Riordan and filed a writ of habeas corpus in the California District Court on October 2, 1895 (Application of Wong Kim Ark; Frost 52; Lee 103). Wong Kim Ark argued that he was unlawfully detained and claimed he was a “native-born citizen under the Fourteenth Amendment.” On January 3, 1896, District Court Judge William Morrow upheld Wong Kim Ark’s birthright citizenship and ordered his release upon payment of a $250 bail (Berger 1230, 1246; Lee 103-105).

The U.S. government appealed Judge Morrow’s ruling to the Supreme Court. The ultimate question considered by the Supreme Court was “whether a child born in the United States, of parents of Chinese descent, who, at the time of his birth, are subjects of the Emperor of China, but have a permanent domicil and residence in the United States, and are there carrying on business, and are not employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China, becomes at the time of his birth a citizen of the United States by virtue of the first clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the Constitution” (Wong Kim Ark 653).

In a 6-2 decision, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Wong Kim Ark on March 28, 1898. The court argued that both the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the Fourteenth Amendment firmly established birthright citizenship, which was not affected by naturalization laws that only applied to White or Black persons. The court determined that because Wong was born in the U.S. and his parents were not “employed in any diplomatic or official capacity under the Emperor of China,” he was a citizen and exempt from the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act (Wong Kim Ark 649, 675-676). As explained on the following page, this landmark decision affirmed that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed citizenship to people born on U.S. soil regardless of racial descent (except for Native Americans), a decisive interpretation of naturalization that still stands today.