Federalism and John Roberts

"...despite the tradition of equal sovereignty, the Act applies to only nine States (and several additional counties). While one State waits months or years and expends funds to implement a validly enacted law, its neighbor can typically put the same law into effect immediately, through the normal legislative process. Even if a noncovered jurisdiction is sued, there are important differences between those proceedings and preclearance proceedings," (570 U.S. 529, 11).

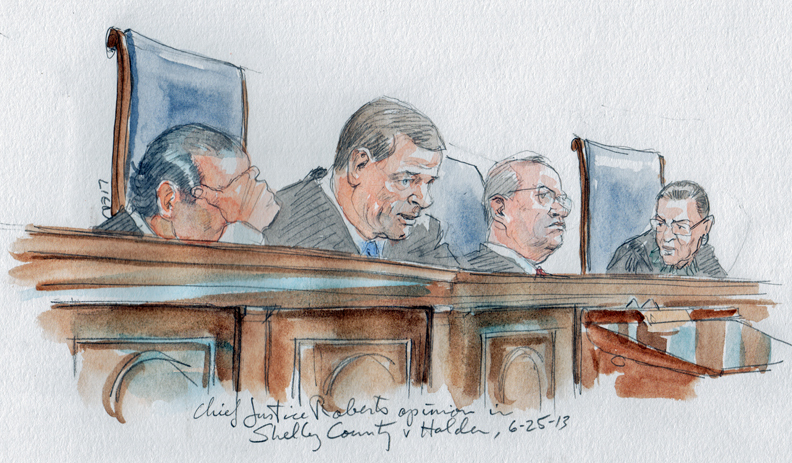

Chief Justice John Roberts writes for the majority, holding that congress exceeded its authority in reauthorizing section 4(b), thus placing a permanent injunction against its enforcement. Although the Court did not rule explicitly on the question of section 5, because §5 applies only to those jurisdictions singled out in §4(b), it is functionally overturned by the injunction against §4(b).

The majority reasons that the burden placed on the states by §4(b), particularly with regards to the principle of “equal sovereignty”, is not justified by the current state of voting rights in covered districts. In particular, they argue that the VRA’s departure from the principles of federalism and equal sovereignty were justified at the time of its enactment due to a “blight of racial discrimination in voting,” which, “infected the electoral process,” (South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966)), but that the circumstances which justified the act are no longer present to a significant enough degree to necessitate the continuation of the VRA (570 U.S. 529, 12). According to Roberts the Act, “employed extraordinary measures to address an extraordinary problem,” (570 U.S. 529, 1), arguing that the VRA was only constitutional in regards to the particular, unique set of circumstances it was written in. In this interpretation, the VRA is almost presumptively an overstep of Congressional power– an overstep which is granted legitimacy by national crisis. Therefore, as the severity of the crisis (racial discrimination) has decreased, so has the legitimacy of the VRA.

The opinion furthers this line of reasoning, stating that decreasing discrimination in covered districts should be followed by increasing leniency in federal oversight. Roberts takes issue with the prior renewals of the VRA which, among other things, amended §5 to further prohibit laws which had the effect but not intention of discriminating on the basis of race. Roberts writes, “...the bar that covered jurisdictions must clear has been raised even as the conditions justifying that requirement have dramatically improved,” (570 U.S. 529, 17). He legitimizes this claim by comparing voter registration statistics from the original passing of the bill in 1965 to those in 2006. In particular, he cites a House Report on voting statistics stating that, “the number of African Americans who are registered and who turn out to cast ballots has increased significantly over the last 40 years, particularly since 1982,” (H.R Rep. No. 109-478, p.12 (2006)) and furthermore, “...there has been approximately a 1,000 percent increase since 1965 in the number of African-American elected officials,” (570 U.S. 529, 14).

Roberts concludes the opinion together by arguing that, in light of the improvements made by the covered jurisdictions in decreasing voter discrimination, the VRA’s ‘disparate geographic impact’ is no longer justifiable. In his mind the VRA was a, “drastic departure from the basic principles of federalism,” (570 U.S. 529, 1) which was out of line with both the principles of individual state sovereignty, and of equal sovereignty. Claiming that the burden placed on equal sovereignty by §4(b) must be justified by ‘current needs’, Roberts writes that, “the coverage formula met that test in 1965, but no longer does so,” (570 U.S. 529, 18). Thus, section 4(b) is overturned. Justice Antonin Scalia wrote a concurrence in which he argues that, for the same reasons 4(b) is overturned, so should be section 5.