The Opinion of the Court

The opinions presented by Supreme Court Judges in United States v. Cruikshank articulate an understanding of Federal power as very limited in scope. Their interpretation of Federal jurisdiction places power in the hands of the State by giving solely State courts the responsibility of maintaining the rights of their citizens. The Judges also limit the applicability of the 15th Amendment and the Civil Rights Act of 1866. To enter Federal jurisdiction in such cases, they require that the prosecution must prove that it was the defendants’ explicit intention to oppress a person or people because of their race.

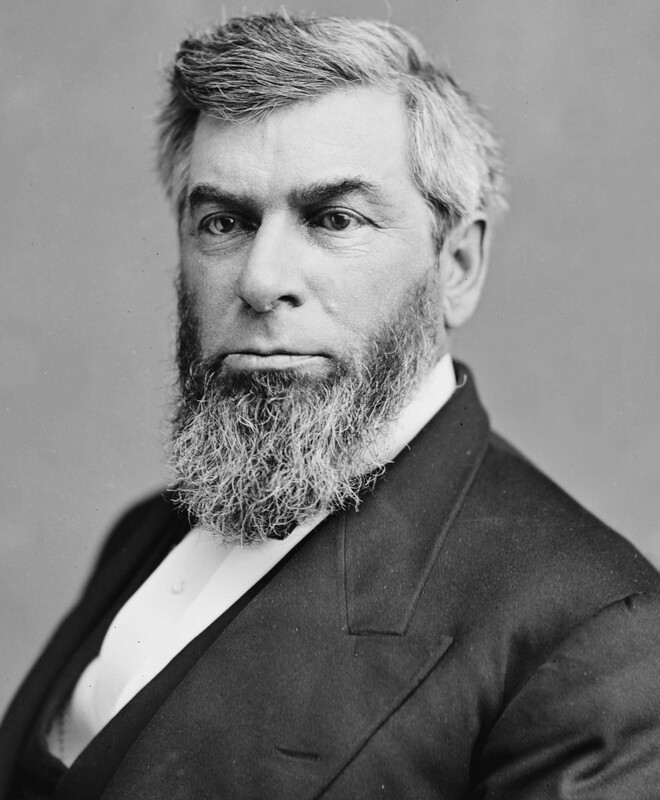

“MR. CHIEF JUSTICE WAITE delivered the opinion of the court,” (8).

Justice Waite first sets the requirements the case must meet in order for it to enter Federal jurisdiction. Many charges are made in the original case. The only one of those charges that could qualify this case for Federal oversight, in Waite’s opinion, must be that the defendants banded together with intent “to hinder and prevent [the victims] in their free exercise and enjoyment of rights and privileges ‘granted and secured’ to them ‘in common with all other good citizens of the United States by the Constitution and laws of the United States.’” (92). Crucially, Waite says that intent must be established. It is not enough to show that events took place. Furthermore, the intent must be to violate rights of the victims that are secured by the Constitution and laws of the United States. Waite does not simply say the victims’ rights because he means to draw a sharp distinction between rights guaranteed by the United States as a Nation and the rights that individuals receive as a citizen of a given State.

Of the Federal Government, Justice Waite says, “Its powers are limited in number, but not in degree,” (92). By this he means that when State and Federal powers conflict, Federal power eclipses that of the State. But the range of Federal action is strictly enumerated in the Constitution. Federal law cannot take precedence unless the case qualifies under conditions stated in the Constitution. Waite posits that the Federal government does not in fact grant citizens rights, and the rights enumerated in the constitution only serve to restrict the power of the Federal Government. The rights that Americans have, he claims, “existed long before the adoption of the Constitution of the United States,” (11). The right of free speech, for instance, does not originate in the First Amendment of the Constitution, but in the laws of civilization, recognized throughout the world. This belief in the exteriority of inalienable rights may make us wonder: Who, then, is responsible for protecting these rights? Waite responds that “the Government of the United States, when established, found [the right to free speech] in existence, with the obligation on the part of the States to afford it protection,” (11). His argument here is that the Constitution has jurisdiction only over actions taken by the Federal Government. Continuing the free speech example, he says, “The First Amendment to the Constitution prohibits Congress from abridging ‘the right of the people to assemble and to petition the government for a redress of grievances.’” Justice Waite does not say that the First Amendment guarantees citizens of the United States their right to assemble. It only says that the Federal Government itself cannot abridge that right. Waite makes a brief aside to say that if the case had alleged that the specific intention of the defendants was to infringe the victims’ First Amendment rights, “the case would have been within the statute, and within the scope of the sovereignty of the United States. Such, however, is not the case,” (12). Doesn’t this last jab at the case contradict his argument? If the sole purpose of the First Amendment is to prevent oppression by federal power, why would proof that one individual meant to take that right from another qualify the case for Federal Review?

And why does Judge Waite spend so much of his opinion attempting to clarify the jurisdiction of the Federal Government versus that of the State? Ultimately, this case of the murder of Black voters will be returned to lower court because Waite does not believe it falls under federal jurisdiction. It is the duty of the States to protect natural rights, including the right to life. “Sovereignty, for this purpose, rests alone with the States,” (13). Furthermore, Waite believes that “The Fourteenth Amendment prohibits a State from depriving any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law, but this adds nothing to the rights of one citizen as against another,” (92). That enforcement belongs to State jurisdiction. Here, again, Waite complicates his own argument that Federal Law only serves to restrict Federal power. He says that the Fourteenth Amendment cannot apply to the rights of one citizen as against another. In his First Amendment argument, he lamented that if only the case proved the intention of one citizen to abridge another’s right to free speech, it would fall under Federal jurisdiction. When it comes to the Fourteenth Amendment however, he says nothing of such a proof of intent qualifying this case. How are these two statements tenable in the same opinion?

Waite is satisfied with his establishment of jurisdiction. He proceeds to dismiss the possible application of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 and the 15th Amendment in this case. The Civil Rights Act of 1866 does not apply because “it is nowhere alleged in these counts that the wrong contemplated against the rights of these citizens was on account of their race or color,” (14). Again, a lack of proven intent is invoked here to invalidate legislation meant to protect rights. The 15th Amendment is disqualified as it only protects from racial discrimination against voters. Waite critiques that “There is nothing to show that the elections voted at were any other than State elections, or that the conspiracy was formed on account of the race of the parties against whom the conspirators were to act. The charge as made is really of nothing more than a conspiracy to commit a breach of the peace within a State. Certainly it will not be claimed that the United States have the power or are required to do mere police duly in the States,” (92). State elections are protected by State powers, says Waite, and it is not the role of the Federal Government to ensure their fairness. Waite drives the point home that “the right to vote in the States comes from the States, but the right of exemption from the prohibited discrimination comes from the United States. The first has not been granted or secured by the Constitution of the United States, but the last has been,” (15). In other words, whether or not someone can vote in a given State is up to the law of that State. Based on the 15th Amendment, The Federal government may only intervene if someone’s vote is restricted explicitly because of their race.

Waite does not believe that Federal jurisdiction in this case stands up against the burden of proof of intent. “They do not show that it was the intent of the defendants, by their conspiracy, to hinder or prevent the enjoyment of any right granted or secured by the Constitution,” (16).

He continues to complain of the vagueness of the case. He condemns it for only stating the violations of rights that were committed, and not adequately providing evidence of “acts and intent; and these must be set forth in the indictment, with reasonable particularity of time, place, and circumstances,” (17). He is blaming the prosecution for their generalization in stating that rights such as life were violated by the acts of the defendants. One may wonder what rights are not infringed upon when people are killed. However, this nit-picking is secondary to Waite’s main argument of jurisdiction, or lack thereof, which he has proven to his satisfaction.

Justice Clifford’s dissent formulates many of the same opinions, but emphasizes that Federal intervention would be merited if the vagueness of the case did not prohibit it.

Returned to lower court. “The order of the Circuit Court arresting the judgment upon the verdict is, therefore, affirmed; and the cause remanded, with instructions to discharge the defendants,” (18).