The End of Reconstruction

This era of the Waite Court is often cited as the beginning of the undoing of the Reconstruction amendments. Scholars have blamed the Court’s limited interpretation of federal jurisdiction for allowing the retreat of Northern forces from the South and a return to a “local rule” which meant open violence on Black Southerners and unfulfillment of promised citizen rights. Cruikshank is identified as a landmark decision in this disarmament. “The decision did not preclude future federal prosecutions… But it certainly encouraged further violence,” (Foner, 146). Foner argues that while the ruling did not restrict federal power further than was designated by the amendments, it did not enable greater enforcement either. Others have been less generous. In “Facing the Ghost of Cruikshank in Constitutional Law,” Martha T. McCluskey notes that “Louisiana’s governor reported to Congress that Cruikshank ‘establish[ed] the principle that hereafter no white man could be punished for killing a Negro,’” (McCluskey, 281). She argues that Cruikshank destroyed federal attempts at racial justice in the South as “it gutted the Fourteenth Amendment privileges and immunities clause; it established a narrow state action limit on due process and equal protection; it imposed a strict racial intent requirement; and it narrowed Congress’s power granted by the Reconstruction Amendments,” (McCluskey, 285).

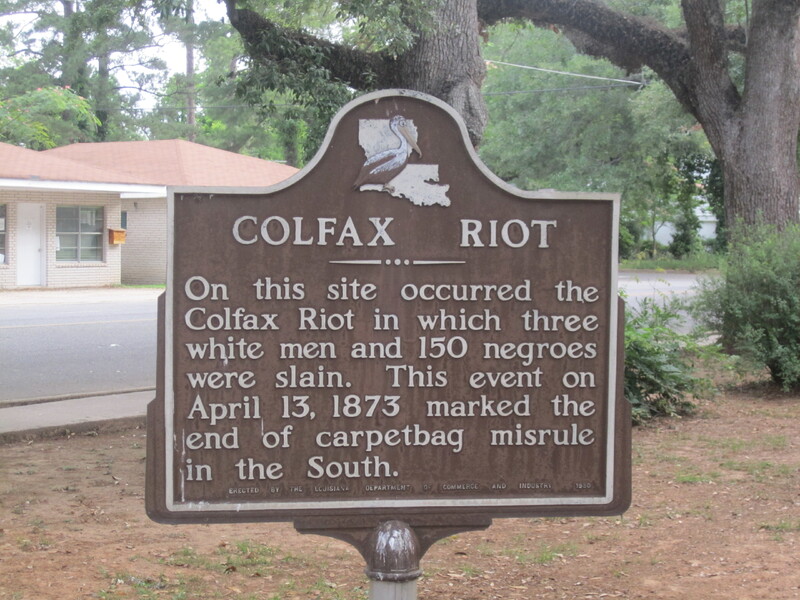

The case was certainly celebrated by Southern Democrats. The federal government had failed to condemn what they saw as a revolt against Northern influence. In 1951, the massacre was commemorated with this plaque (left). The sign claims that “This event on April 13, 1873, marked the end of carpetbag misrule in the South.” This celebrates the massacre as leading to the end of Reconstruction. The Cruikshank case following it is attached to this legacy. The sign was only removed in 2021, just short of its 70th anniversary (Lane, 2021). The removal was controversial even then, as members of the local council resisted its removal.

But the extent to which the ruling in Cruikshank gutted any power endowed by the Fourteenth, established a new limit on state action or narrowed Congress’s power in a substantial way is contested. In “A Judicial Abandonment of Blacks? Rethinking the ‘State Action’ Cases of the Waite Court,” Pamela Brandwein argues that when put in its proper context, Cruikshank is not a remarkable check on federal power. She says that the case actually worked to establish what a proper prosecution should be under the Reconstruction amendments and other legislation. The fact that the case addresses indictment counts falling under equal protection, which were not meant to be argued before the Supreme Court, indicates that the judges meant to aid the executive in crafting successful indictments in the future. She emphasizes Foner’s point that it did nothing to prevent future indictments (Brandwein, 362). And she explains the establishment of intent as necessary under the existing legislation. “Because Colfax was both a racially and politically motivated massacre, Justice Bradley's insistence on the allegation of a racial motive served notice that politically motivated violence was outside the reach of Section 5,” (Brandwein, 362). She critiques recent interpretations of the case for assuming a standard of proof of intent familiar to current Court proceedings. But this standard did not exist at the time. “The Waite Court left the standard of proof [ of racial motivation] on this matter unclear,” (Brandwein, 362).

I do not find the lack of standard at the time to be a sufficient excuse for cementing the burden of proof of intent. I also do not believe that the interpretation of constitutional language as serving only to restrict federal action is the natural reading. I am intrigued by Brandwein’s point that the criticism of the vagueness of the indictment could have helped future prosecution. But did it? I think the value in Brandwein’s point is that it turns our attention towards the flaws in the original amendments and Reconstruction legislation. We may critique the requirement of racial animus in the Fifteenth amendment, and the lack of state oversight in the Fourteenth. It may be that the legislation was built faultily in its text, and not only spoiled by interpretation. The interpretation practice is always unstable. What was interpreted to politically advantage one side can be flipped with a change of justices. But not all documents are equally up to the whims of interpretation. With this critique, we can go beyond laying full blame on the Post-Reconstruction Court, and acknowledge the failures of legislation that came before.