The Colfax Massacre

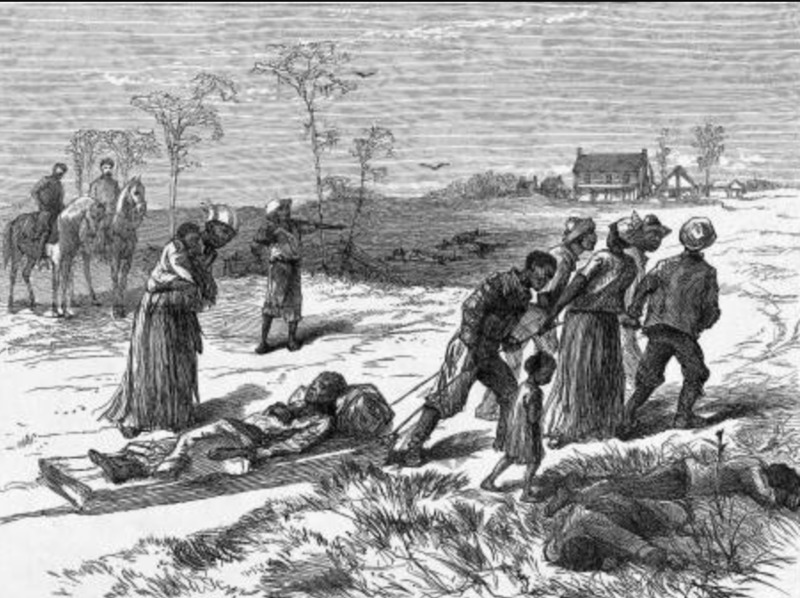

Illustration of the Colfax Massacre entitled "The Louisiana Murders—Gathering The Dead And Wounded." Published in Harper's Weekly, May 10, 1873.

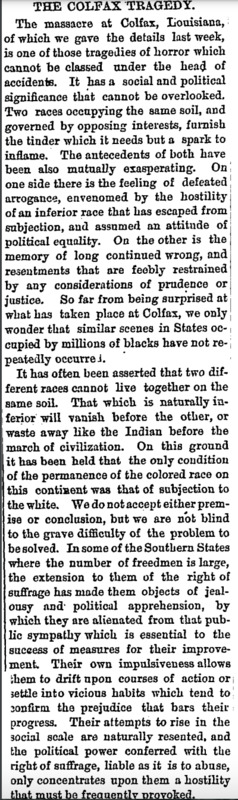

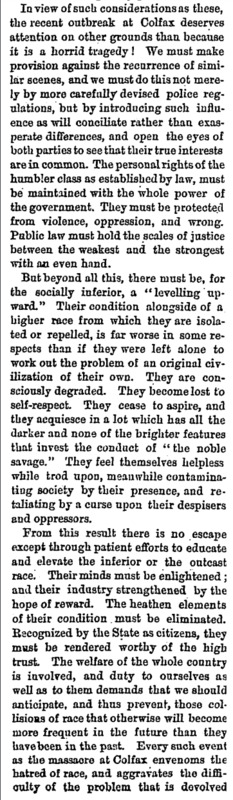

Northern reception of the news from the South shows the Northern Republican understanding of the need for federal power to ensure the civil rights of Black people in the South. It also highlights the hypocritical nature of Northern progressives who, on the one hand, preached liberation and equality, while simultaneously blaming Black people for their own condition of oppression. While the illustration here indicates sympathy for those killed and the larger community, the New York Evangelist article (below) complicates that narrative. Yes, the massacre is declared a “Horrid Tragedy!” many times. But the author provides no specifics of the victims, perpetrators or scene which would bring specificity to the article. Instead they focus on a refutation of the argument that “two different races cannot live together on the same soil,” (New York Evangelist, 4). They say that this argument is born of the jealousy of Southerners over the emancipation of Black people, but also from the behavior of Black people themselves. “Their own impulsiveness allows them to drift upon courses of action or settle into vicious habits which tend to confirm the prejudice that bars their progress,” (New York Evangelist, 4). It is their inferiority, the article claims, that draws upon Black people a natural resentment, and requires “patient efforts to educate and elevate the inferior or the outcast race. Their minds must be enlightened,” (New York Evangelist, 4) presumably by Northern intervention. Along with these ideas rooted in a hierarchy of races, there are calls for proper federal action, and for justice with an even hand.

But public calls in the North for further federal intervention had their fair share of objectors, and shortly after this time would lose political momentum. The Colfax Massacre was inextricably linked to the Louisiana gubernatorial election of 1872. A state election with national issues, both the candidates claimed victory. White Democrats killed over 150 Black Republicans and Black state militia, who were asserting their position they had won in the election. Trapped inside a courthouse, Black voters held out a flag of surrender as their White attackers set fire to the roof of the building. Those who fled the flames were shot. The majority of the Black people who were killed had already surrendered (Tucker, Introduction). This massacre was hardly anomalous. As a report from the U.S House of Representatives from 1874 attests, violence against Black voters was commonplace in Louisiana, multiplying around election time (George F. Hoar et al., 12). Southern interests maintained that the unfortunate events could only be explained as "the results of the misrule and oppression of the Southern States at the hands of the Federal power," (Committee of 70, 13).

The Southern interest seemed destined to win out from the beginning. Although almost 100 people were originally indicted for conspiracy in the Colfax Massacre, only a handful stood trial in federal court. The Enforcement Act of 1870 was employed in the indictment, but the local white community prevented most of those originally indicted from facing trial (Foner, 144). Only three defendants were convicted, but Supreme Court Justice Bradley found even this to be unacceptable. Sitting the bench of the circuit court, he formulated many of the arguments that would later appear in the unanimous Supreme Court opinon. Namely, that the protection of the right to life was left up to the states, and that intent to oppressed based on race would have to be proven for Cruikshank to fall under federal jurisdiction (Foner, 145).