The Facts

The Shelley family’s story is illustrative of many of the systemic barriers to economic prosperity that Black families faced during the 1930’s and 40’s, as well as the ingenuity those such as the Shelleys employed to overcome these barriers. Like many others, J.D. Shelley and his family moved from rural Missouri to St. Louis in hopes of escaping racial violence and in search of economic opportunities; Mr. Shelley moved to the city first and worked as a mechanic in a segregated factory, eventually saving enough money to move the rest of his family to the city (Gonda, 34). Mr. and Mrs. Shelley, along with their six children, shared a small apartment in a segregated neighborhood. Eventually, concerns about their children’s safety and the lack of space within their apartment led the Shelleys to consider buying a home. The family reached out to their pastor, Robert Bishop, who worked as a part-time realtor to aid them in their search (Gonda, 35).

After investigating their options, the Shelleys decided on a home on 4600 Labadie Avenue in St. Louis, a more middle class neighborhood compared to where the family lived previously. Bishop arranged for a “straw party”, a white woman named Josephine Fitzgerald, to purchase the home on the family’s behalf. Usage of straw parties was common amongst Black realtors and home buyers at the time in order to circumvent covenants and more easily receive financing (Gonda, 35). Yet Bishop and the Shelleys had falsely assumed that the home was not subject to a racial covenant, considering that the neighborhood was integrated and several other Black families were already living on the block when they moved in, and had since the 1880’s (Gonda, 36). Yet the covenant in the home’s deed (as quoted above) had been on the books since 1911, covering a patchwork of homes across the neighborhood and likely aimed at maintaining a white majority in the already integrated neighborhood (Gonda, 37).

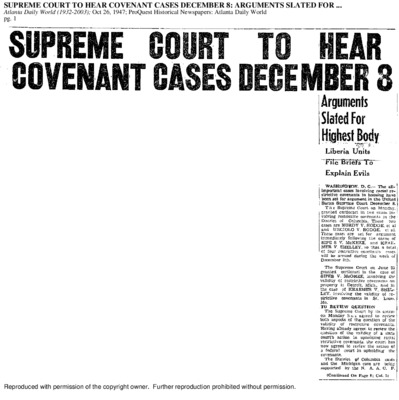

Louis D. Kraemer was a white neighbor who lived in a nearby home whose deed also contained the same covenant as the Shelleys new home. In November 1945, Kraemer sued the Shelleys in the St. Louis circuit court in order to prevent them from acquiring the property. The Shelleys, financially backed by Robert Bishop and the Real Estate Brokers Association, a group of other Black realtors, won their case in state trial court (Gonda, 52). Kraemer then appealed the ruling, and the Missouri State Supreme Court overruled the trial court on December 9th, 1946, prompting the Shelleys to appeal the case to the United States Supreme Court.

Represented by attorney George L. Vaughn, the Shelley family’s case was finally argued before the Supreme Court on January 14th 1948, and decided on May 3rd of that year. The court ruled unanimously in favor of J.D. Shelley, yet three of the nine justices had to recuse themselves from the case because they owned property covered by racially restrictive covenants (Rothstein, 91). This decision represented a significant shift in the court’s understanding of the concept of “state action”, as explained on the following page.