Historical Context: Covenants & Housing Discrimination

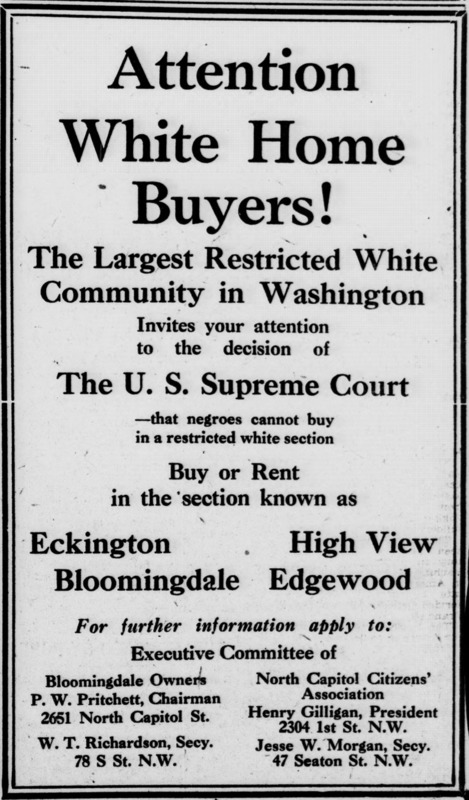

Though they existed before the case was decided in 1917, the story of racial housing covenants in the United States can largely be understood as a reaction to Buchanan v. Warley (Rothstein, 78). As the above quote from Shelley outlines, the Buchanan ruling deemed that city ordinances which restricted sales of property to prospective Black buyers in white-majority neighborhoods were unconstitutional. Yet this ruling explicitly applied to governmental action, and did not explicitly speak to the actions of private companies or individuals. Housing covenants, racially restrictive clauses in the deeds of homes which dictated who could own or live on the property, thus emerged as an alternative means to continue the segregation of neighborhoods across the country. Covenants could also take the form of neighborhood-wide contracts requiring current residents to agree to not sell their homes to Black families (Rothstein, 79). These contracts were often required for membership to a “community association”, groups formed by developers to ensure that new properties remained segregated. Violation of either form of covenant could end in litigation targeting Black families who moved into these neighborhoods and/or white former owners who sold their homes to these families.

Yet neighbors and developers weren’t the only ones responsible for the creation of covenants; the insidious power of these clauses rested in the way they were enforced by multiple levels of private institutions and governmental power. For one, these covenants were upheld and enforced in hundreds of state-level court cases, often leading to the forced eviction of homeowners (Rothstein, 82). The Federal Housing Association (FHA) also encouraged the inclusion of covenants in deeds for new homes as a way for developers to receive a lower risk assessment score, making it easier for them to receive FHA loans (Rothstein, 84). Private groups, including the National Association of Real Estate Brokers (NAREB) also encouraged covenants and other means of discrimination as a way to prevent “objectionable use” of properties (Gonda, 24). By framing these issues of segregation in terms of the economic principles of risk assessment and property values, institutions such as the FHA and NAREB could retain the appearance of neutrality while utilizing language and standards that were racially-coded, and even openly discriminatory.

The 1940’s and the impact of World War II brought additional barriers to housing for Black families. An increase in internal migration towards cities and the collapse in construction rates brought about a housing shortage in most urban areas. By 1945, the city of St. Louis had a housing vacancy rate of 1% (compared to the normal rate of 5%) while a city commission estimated that at least half of existing homes were “in decay” or worse (Gonda 19-21). This lack of available housing, combined with covenants and other forms of racial discrimination, created a “double barrier” to Black homeseekers. This double barrier forced many Black Americans into a system of “rental capitalism” in which their only option was renting expensive and low-quality properties in segregated neighborhoods, often preventing them from accumulating wealth through home equity in the same way that white homeowners could (Connolly). Moreover, the 40’s saw an uptick in racialized violence related to space and property, including acts of vandalism, arson, and bombings perpetrated agaisnt Black residents and landowners (Gonda, 23). Scholar N.D.B. Connolly points to this combination of extralegal and legal violence as the imposition of “white popular sovereignty”: the idea that white Americans constitute “the American people” and get to retain their sovereignty above that of the government itself (Connolly). Through this lens, it becomes evident that racial covenants were just one means for white homeowners to assert their perceived sovereignty and maintain segregation within their communities all while receiving systemic support from private and public institutions.