Segregation and Racialization in California (1850-1947)

Useful Labor or Dangerous Other?:

Whites had two contradictory desires following the incorporation of California as a State. One, they sought to create a racially ‘pure,’ wholly White society for themselves along the Pacific Slope, and two, they required cheap labor to build it(Hernández, 37, 38). During the Gold Rush, White settlers committed mass acts of violence and enslavement against Indigenous Californians and compelled them to labor for their benefit. This, alongside rampant disease, precipitated a rapid population collapse, where by the end of the century the population had declined by 90%(Hernández, 40). Searching for another source of cheap labor, agribusiness and rail companies recruited Chinese laborers. Chinese immigrants were soon subjected to the process of negative racialization as they became the largest minority group in the state by 1870. They were characterized as, “Dirty, depraved, and disease ridden,” and eventually this negative stigmatization would lead to the passage of the Chinese Exclusion act of 1882(Roberts, 101). Although the state legislature had taken swift action in the 1850s to prevent the migration of Black Americans, the small number of Black migrants who did move to the state proved to be politically adept. They used their small numbers to their advantage, and were able to effectively leverage their position as a relatively non-threatening, politically engaged minority to extract major concessions from both the state and localities(Hendrick, 50-51). This is not to say that this was not hard fought, but rather displays the unique trends of racialization in the state.

Latino Racialization in California:

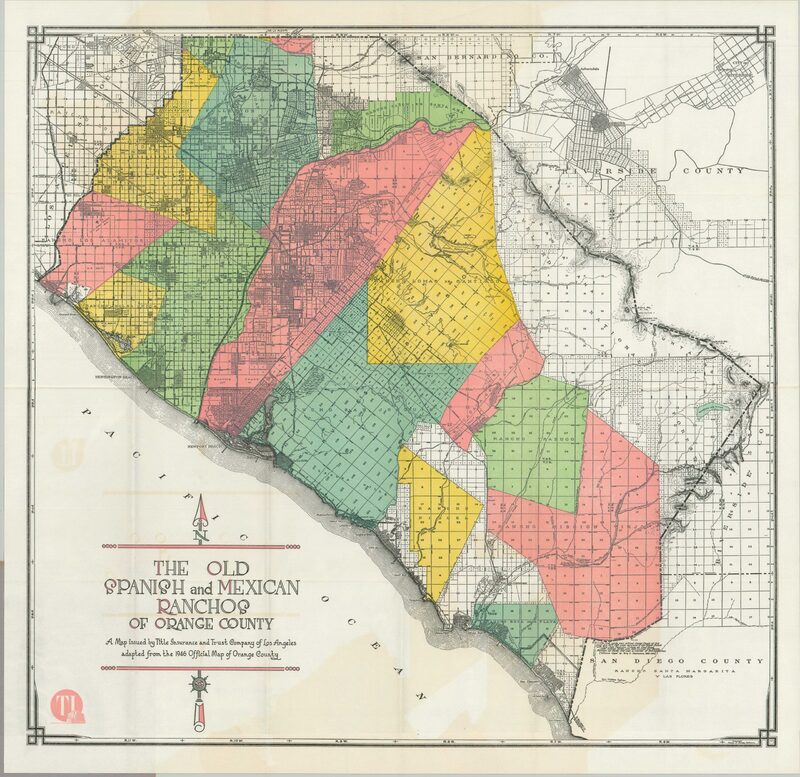

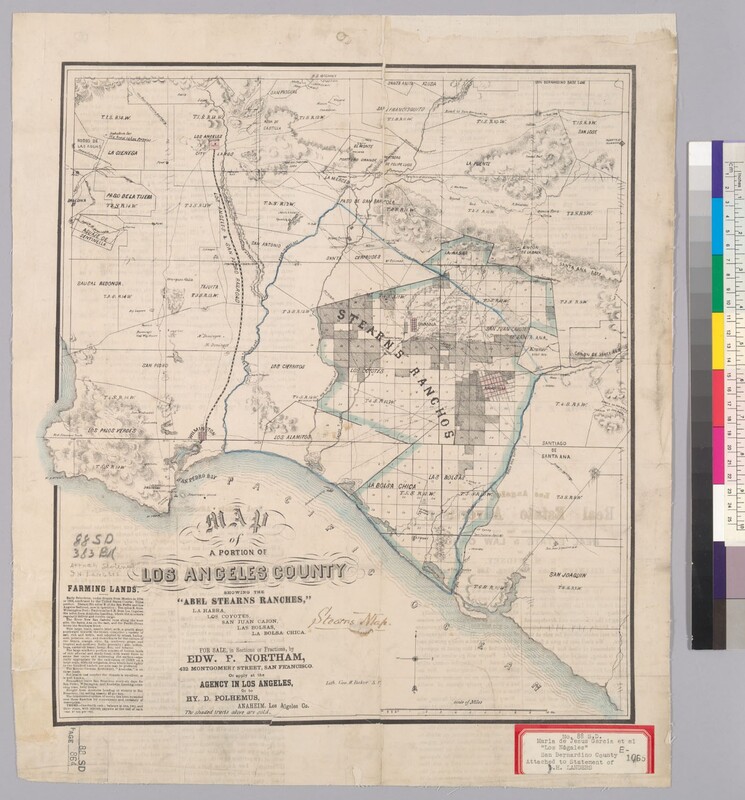

The racial position of Latino Californians can be characterized as having two periods, the ‘Californio’ period, stretching from 1850 to about 1910, and the Immigration period, which stretches from 1910 up until the modern day. The Californios were the descendants of Spanish and Mexican migrants that had traveled to the state between the 17th and 19th centuries. Some of them had actually been seeking an avenue of escape from the Spanish Casta system, a strict racial hierarchy that ruled over the Spanish colonies(Hernández, 27). Under the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, the Californios were granted not only citizenship, but also property protections.

By the time the treaty had actually come into effect, White settlers had already gone to great lengths to delegitimize and exterminate Californio land claims(Hernández, 29). This was made worse by the state legislature’s imposition of a high property tax burden, which despite being racially neutral on its face, had the effect of making Californio land claims untenable. Even so, the Californios were also identified as an integrateable class capable of ‘Americanization’ due to their comparably small numbers and middle class status. By the dawn of the 20th century, Californios had obtained a degree of ‘whiteness:’ they attended integrated schools, were relatively prosperous, and co-existed with Whites in general society, but the State’s industries still hungered for cheap labor, and soon another group would be found to fill the gap(Arriola, 169).

1910 constitutes the beginning of the ‘Immigration’ period of Latino racialization, albeit this racialization was often uneven, and typically applied on class lines. The 20th century witnessed an explosion in the Mexican American population in Southern California, with over a million Mexicans migrating north of the border between 1910 and 1930(Ruiz, 23). Nativist fervor would explode among Whites at both the state and national levels, and many pushed for the passage of the National Origins Act of 1924, which sought to drastically reduce immigration levels to the country(Hernández, 132-133). Interestingly, it would be Agribusiness executives that would come to bat for Mexican immigrants, but it was hardly for humanitarian reasons. California agribusiness executives argued before Congress that Mexicans were not a static population, but rather, “birds of passage,” whose homing instincts would eventually lead them home(Hernández, 136). Knowing that their more eclectic arguments might not resonate with the nativists, agribusiness also assured Congress of the deportability of Mexicans, and used various race-baiting tactics to make them fear Black migration to the, “Final frontier of Anglo-America.” As a result of their efforts, agribusiness extracted the ‘Hemisphere Exemption,’ which allowed for an unlimited number of migrants to pass into the United States, albeit with greater tools to criminalize, ‘illegal immigrants.’ (Hernández, 138)

California School Segregation (1850-1910):

Although the widespread segregation of Mexican American children would not occur until the 1920s and 30s, it is nevertheless important to understand the complex and back-and-forth history of school segregation in California. From the state’s founding in 1850 until about 1890, there was a relentless battle between the White state government and the disunited forces of Black, Chinese, and Indigenous Californians. Although technically a ‘free’ state, the Superintendent of Public instruction would interpret the School Census Act of 1852 as solely providing funding to schools based on their white student population, barring minority children from education entirely(Hendrick, 15). Only in 1860 would the state legislature allow for school districts to establish separate schooling for minority children, however even then most didn’t. The Civil War would see Republicans sweep into power in 1863, and they would in turn pass a new school bill requiring the establishment of schools for non-white children. Nevertheless, 1867 would see a severe reaction against these reforms, resulting in Democrats retaking state office and rolling back minority gains(Hendrick, 38). Notably, their newly revised school bill would have, ‘Mongolian,’ children entirely barred from schooling. Both Chinese and Black Californians would push against this status–quo, with the Black community seeing more success.

In Ward v. Flood (1874) the state Supreme Court would affirm segregation, but leave an important carveout: so long as no separate schools were maintained, Black children(and Indigenous children) had the right to an education. Black parents would go on to boycott the designated ‘Colored’ schools, and successfully force school districts all across the state to close Colored schools and integrate Black children(Wollenberg, 318). Chinese Californians had no such luck, first being excluded from education entirely, and later having their segregation mandated by state law—something the Black community was able to avoid(Hendrick, 39, 58, 60).

California School Segregation (1910-1947)

1913 would see the establishment of the first ‘Mexican’ school in Pasadena, California, and they would rapidly proliferate across the state(Cooper, 8). Usually this was seen in a process of tipping points: as the Mexican American population reached a certain threshold (about 50%), White parents would push for segregated schools, even if they weren’t allowed by law. Fearful of White parents’ wrath and losing valuable tax dollars, districts acquiesced to their demands. Even then, this process of segregation was uneven and along class lines, allowing for middle-class Mexican Americans to remain politically inactive, seeing their own position as relatively secure(Wollenberg, 321). Meanwhile, Mexican-American laborers lacked both the time and money to levy any sort of major opposition until the mid-1940s.

There were important instances of Latino opposition to the segregation of their children. Alvarez v. Lemon Grove School District (1931), was the first successful desegregation case Mexican Americans achieved, seeing them push against the ‘Americanization’ argument of separate schooling, and obtaining an integration order(Ruiz, 25-26). Unfortunately, the case’s influence was limited, and never went beyond the local level. By 1945, Mexican American children were the most segregated student demographic in the entire state, despite not being a segregatable group by state law(Race Nat Seg, 318). With increased Latino confidence following WWII, as well as general frustration with the status-quo mounting, something was bound to give. And soon, tensions would finally erupt in the city of Westminster.