Sharecropping Through the Lens of the Cash Crop and The Failures of the Supreme Court

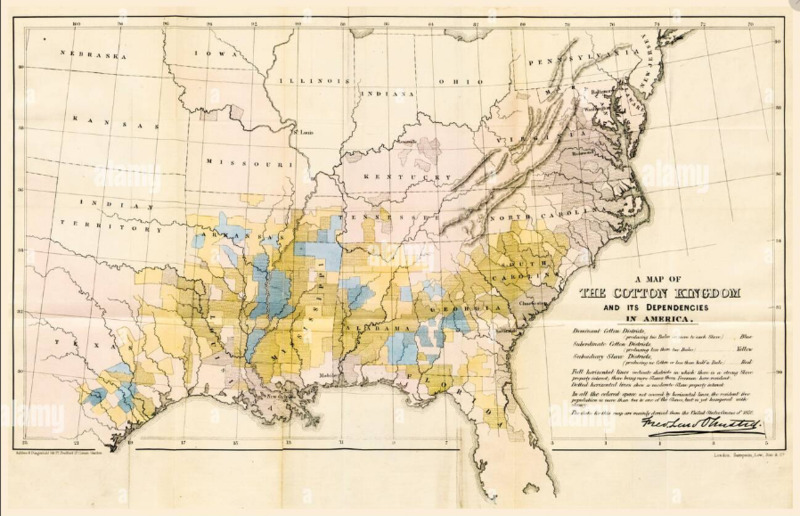

The older map of the Cotton Kingdom identifies the core cotton-producing regions of the nineteenth-century United States. Cotton cultivation is concentrated in a broad belt stretching from eastern Texas across the Gulf South, through Mississippi and Alabama, into Georgia and the Carolinas. This belt corresponds closely to fertile soils, warm growing seasons, and access to rivers and railroads. Cotton organized space and determined where plantations were profitable, where capital flowed, and where labor was concentrated. It thus structured settlement patterns, transportation networks, and the distribution of economic power across the region.

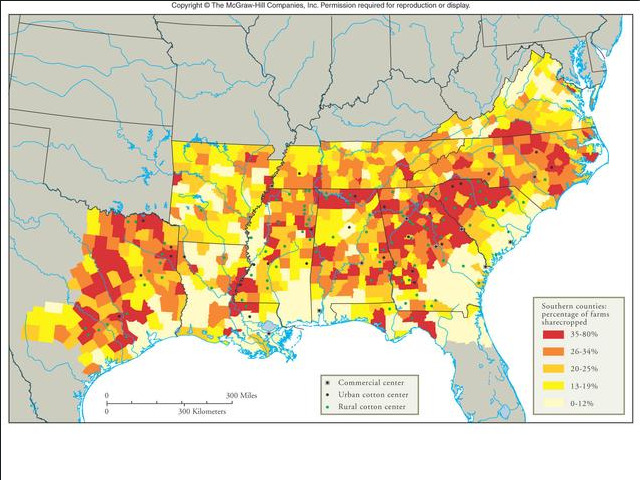

The second map, showing the percentage of farms that were sharecropped by county around 1900, shows how this same cotton-centered agriculture continued after emancipation in a new form. The darkest concentrations of sharecropping appear in the Mississippi Delta, the Alabama Black Belt, central Georgia, eastern Texas, and parts of the Carolinas are regions that align almost exactly with the heart of the Cotton Kingdom. Counties that had been most intensively devoted to cotton before the Civil War became the counties where sharecropping was most prevalent afterward. The maps together envisage a transformation in the legal and economic structure of labor within the same spatial framework.

The land that was best suited to cotton did not change, and cotton remained the dominant cash crop well into the twentieth century. What changed was the mechanism through which labor was secured. Sharecropping filled the same spatial niche that plantation slavery had occupied. It allowed landowners to continue producing cotton on the same land, using the same ecological advantages, while shifting risk and responsibility onto laborers. Infrastructure, credit systems, settlement patterns, and landholding arrangements persisted across this transition. Together, they reveal a long-term pattern in which land suitable for cotton repeatedly generates labor systems designed to extract value from that land, even as the formal legal status of labor changes.

When this geographic continuity is joined with Bailey v. Alabama, it really creates tension between the material reality of Southern agriculture and the Supreme Court’s reasoning. Bailey’s case arose from the regions where cotton, debt, and labor dependency were spatially entrenched across entire counties. Yet the Court did not address this regional structure directly. Instead, it framed the constitutional violation narrowly, locating it in Alabama’s use of a prima facie evidentiary presumption that treated breach of contract and unpaid debt as sufficient proof of criminal intent.

The Court’s opinion repeatedly emphasizes that the injustice lies in the mechanics of proof. Alabama’s statute is condemned because it collapses civil failure into criminal guilt and instructs juries to accept that collapse as legally sufficient. The Court insists that it does not inquire into the state’s motives or into the broader fairness of its labor system, focusing instead on the statute’s “natural operation.” This methodological restraint allows the Court to invalidate the law without confronting the deeper regional conditions that made such a law effective and attractive. The maps make clear what the opinion leaves unexamined: the statute operated within a landscape where sharecropping and debt were ubiquitous.

By isolating prima facie injustice from the spatial and economic system in which it functioned, the Court treats the statute as a doctrinal misstep rather than as a legal instrument embedded in a durable agricultural order. The overlap between the Cotton Kingdom and sharecropping maps shows that the statute’s reach was not marginal. It applied across counties where unpaid advances were routine and labor mobility threatened the stability of cotton production. The Court condemned the law because it made conviction too easy, not because it made freedom too difficult.

This choice is exactly the limit of Bailey, as the decision draws a constitutional line at evidentiary presumption rather than at structural coercion. It strikes down one mechanism of enforcement while the regional logic that repeatedly produced new statutes. Bailey v. Alabama addressed only the most explicit legal shortcut within this system.