Introduction and Background Context

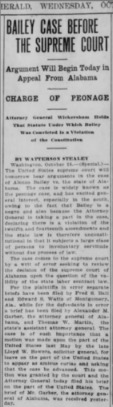

Bailey v. Alabama (1911) stands as a landmark Supreme Court decision, interpreting the Thirteenth Amendment’s prohibition on involuntary servitude and its application to post-Reconstruction labor systems in the South. The case arose out of Alabama’s statute that criminalized breach of labor contracts when an advance had been paid. Under an amended Alabama statute, a worker who accepted money in advance and then failed to perform the promised labor—or failed to repay the debt—could be convicted of fraud, with the unpaid debt treated as “prima facie evidence”, or evidence that, "on its face", showed criminal intent.

Alonzo Bailey, a Black sharecropper, was convicted under this statute after accepting a $15 advance and later leaving his employment without repaying the money. At trial, the jury was instructed that Bailey’s departure and unpaid debt were sufficient to establish fraudulent intent, and Alabama law further restricted Bailey’s ability to testify about his uncommunicated motives for leaving. The case thus turned on a statutory presumption that converted economic failure into criminal guilt.

The Supreme Court reversed Bailey’s conviction, holding that Alabama’s statute violated the Thirteenth Amendment and federal anti-peonage laws. While the Amendment permits involuntary servitude as punishment for crime, the Court emphasized that a state may not manufacture a crime in order to compel labor in payment of a debt. In striking down the statute, the Court recognized that criminal enforcement of labor contracts functioned as a system of coerced labor. Bailey v. Alabama thus shows how formally neutral legal rules could sustain peonage through jury instructions, evidentiary presumptions, and the threat of criminal punishment.