Justice Frank Murphy's 'Dissent' in Hirabayashi v. United States

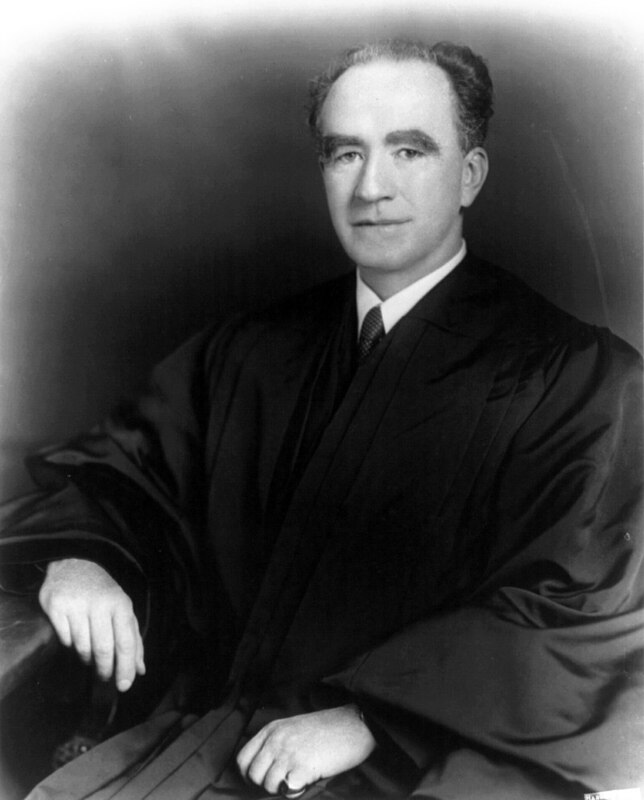

Notably, Justice Frank Murphy had originally written a dissenting opinion in Hirabayashi. Murphy, who had a history of dedication to the cause of civil liberties, was extremely wary of the precedent Hirabayashi could establish. He also believed that, far from being a necessary security measure, the decision could sabotage the United States’ war effort. The discrimination evident in Hirabayashi conflicted with the very principles for which the United States fought, and could have “unfortunate repercussions among peoples in Asia and other parts of the East whose friendship and goodwill we seek… We do not win the war, on the contrary we lose it, if in the process of achieving military victory we destroy the constitutional safeguards and the best traditions of our country.”[10]

However he was eventually persuaded by his fellow Justices to reluctantly submit a concurrence–an opinion which ostensibly agrees with the majority decision, but for different reasons. Given the turbulent wartime atmosphere, the other Justices were anxious to have the Court present a united front on the “troublesome case.” According to legal scholars Sidney Fine and Robert Daniels, Murphy’s ‘concurrence’ retained much of the bite and “sting of a dissent.”[11] This can certainly be seen in lines such as:

“Distinctions based on color and ancestry are utterly inconsistent with our traditions and ideals. They are at variance with the principles for which we are now waging war… To say that any group cannot be assimilated is to admit that the great American experiment has failed, that our way of life has failed when confronted with the normal attachment of certain groups to the lands of their forefathers.”[12]

Or;

“Under the curfew order here challenged no less than 70,000 American citizens have been placed under a special ban and deprived of their liberty because of their particular racial inheritance. In this sense it bears a melancholy resemblance to the treatment accorded to members of the Jewish race in Germany and in other parts of Europe.”[13]

And finally;

“In voting for affirmance of the judgment I do not wish to be understood as intimating that the military authorities in time of war are subject to no restraints whatsoever, or that they are free to impose any restrictions they may choose on the rights and liberties of individual citizens or groups of citizens in those places which may be designated as ‘military areas'.”[14]

Murphy had only concurred with "the greatest reluctance, and, to a degree, against his better judgement" in Hirabayshi.[15] When the Court presided over Korematsu v. United States and subsequent challenge to the exclusion order and internment of Japanese-Americans, Murphy would not hold himself back. Commenting on the exlusion policy advocated by the United States Government, he wrote:

"[This] goes over 'the very brink of constitution power' and falls into the ugly abyss of racism."[16]

Even if the Japanese-American wartime cases of Yasui, Hirabayashi, and Korematsu are some of the darker stains in U.S. Judicial history, Murphy's dissent offers at least one oppertunity for a positive retrospective.