Roots

Date: 8/13/1987

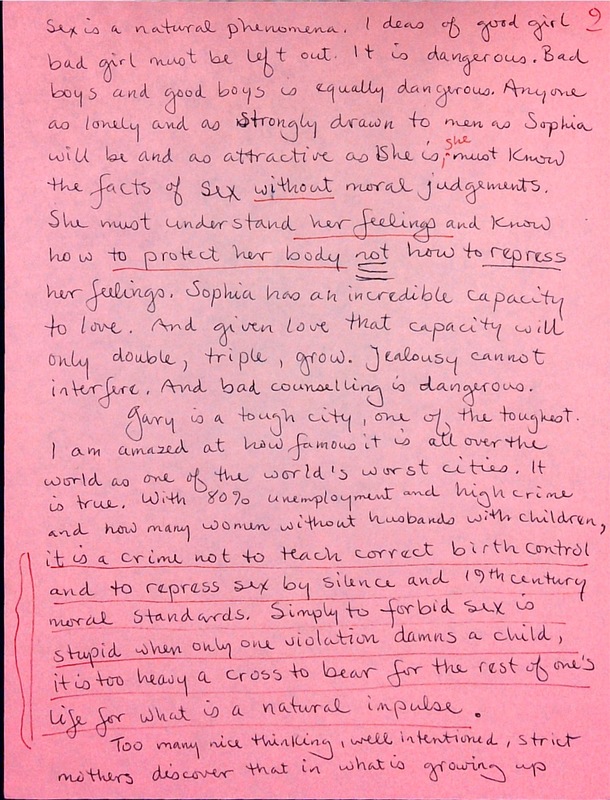

Due to Brown’s sexuality and other conflicts throughout his childhood, José and Dorris Brown had a tenuous relationship. The above letter is the only in the José Brown Papers to have been sent or received by Brown’s mother, Dorris. In this page of the letter he uses the mode of his young cousin, Sophia, to express the negative emotions that he holds around his own upbringing. Specifically he expresses frustrations with the way that Dorris had dealt with sexuality during adolescence, arguing that sex is natural and that mentions of sex should not be coupled with a moral judgment. Brown states in a 1988 letter to George Cummings that he had been celibate his entire life with the exception of only 4 years in the mid-1970s and a few partners in NYC in the early 1980s, suggesting that Dorris’s upbringing was detrimental to Brown’s expression and understanding of sexuality.

Date: 12/11/1968

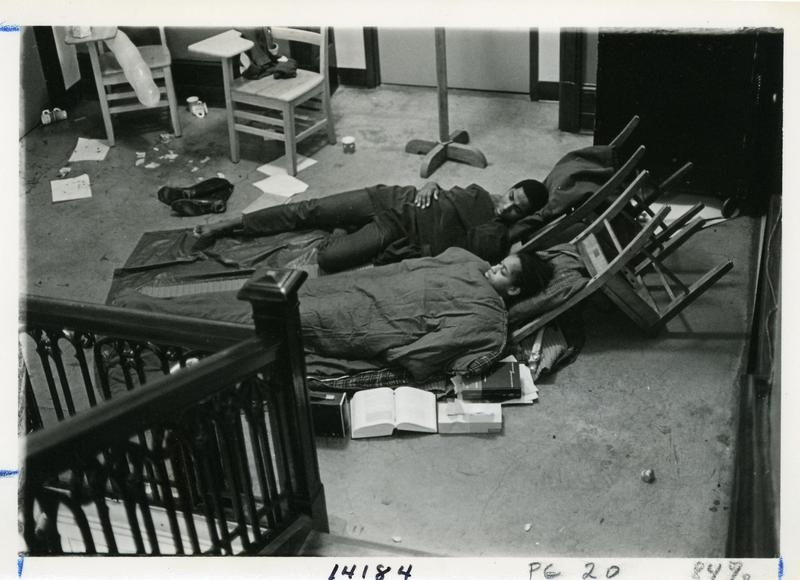

Although Reed College never formally banned any person from enrolling in their program due to gender or race, as an elite college with a very high tuition cost and unapologetically eurocentric curriculum there were very few Black students before the civil rights movement in the late 1960’s began to pick up traction due to national protests. Brown was a participant in the inter-community Reed civil rights protests organized by the Black Student Union for the creation and control of a Black Studies program. The Black Studies program was eventually granted after protests such as the one pictured above where Brown and an unnamed student occupied two administrative offices in Eliot Hall, however it was eventually dissolved only a few years after its creation. The civil rights protests for a less eurocentric curriculum didn’t pick up again until many years later in 2017 when Reedies Against Racism and other groups modeled tactics after the 1960’s BSU to diversify the almost exclusively European humanities program.

Date: 6/27/1987

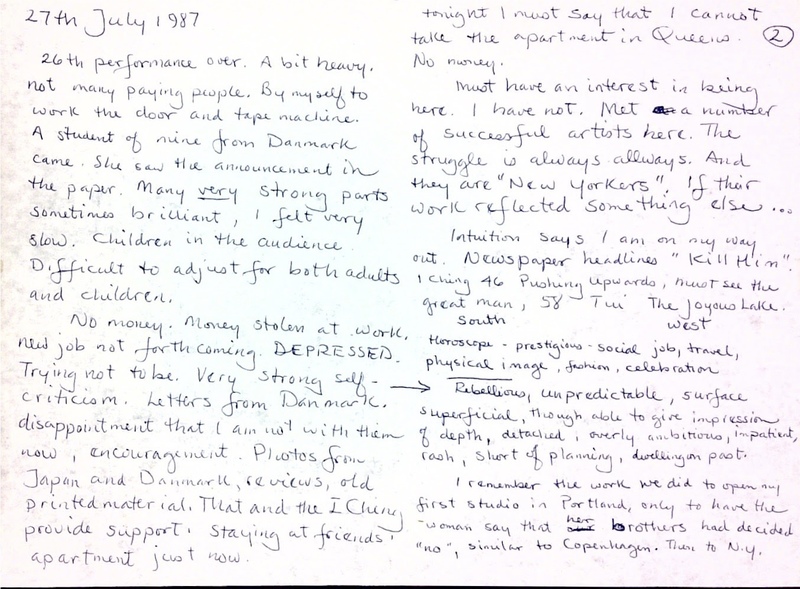

Although this letter is dated later in Brown’s life, it’s almost impossible to discuss Brown without mentioning the immense impact that Reed professor Judy Massee had on him. As Peggy Choy and Megan Nicely expressed, Massee had a very large impact on her students because of her somewhat subversive and postmodern approach to dance training that privileged and cultivated the natural movements and physicality of her pupils. Due to her large impact on Brown’s life and dance philosophy, Brown kept in contact with Massee two decades after leaving Reed. Choy, who was a peer of Brown’s in Massee’s Reed class, remarked at Brown’s exuberant and joyful social quality, something that almost every interviewee contacted for “Changing Tides” mentioned. Although we had no opportunity to view Massee’s mailed responses to Brown or interview either about their relationship, it seems clear that Massee and Brown maintained a mentoring relationship that was likely mutually inspirational.