Legacy

Interview with Cecilia Moreno

In 2017, California signed into law the California Value’s Act, informally sanctioning California a Sanctuary State(link). This is a stark contrast to proposition 187, introduced just 23 years before. What could explain this evolution in policy and public sentiment?

Cecilia Moreno was in her Senior year of high school when Prop 187 was passed. Her father, a foreman, first came to the United States as a migrant worker in the Bracero program in the 60’s. Cecilia was a part of a Mexican-American family that was partially natural-born and naturalized. As the youngest of 7 siblings, her 4 eldest had been born in Mexico and immigrated to the states. She lived in Yuba City, rural central California, where the demographics were polarized: “you had the farmers that were primarily Indian or Caucasian and you had the workers who were primarily Mexican Latino.” She attended Yuba High which reflected the demographics of the city where the different groups “kept their own.” “Rumblings of discussion” around Prop 187 emerged as election season got closer with “a lot of angst against immigrants as a whole.” Her family had been involved in the Chasar Chavez marches and walkouts, so there was no hesitancy to get involved in the movement. When time came for a statewide protest, her parents gave permission and excused her from school because “they understood the cause was greater than myself.” Then 17 she found a group, carpooled, and joined over 250,000 to protest Prop 187.

She remembers the chants.

“La Raza Unida jamas sera vencida!”

“Pete Wilson - Culero - Donde esta el Dinero!”

She went into detail about how all of this was Step 1. “So we were able to do step one where we marched at the capital, but the next step was taking it back to our own schools and this is where it got a lot harder.” Step 2 didn’t have the “unifying force” that Step 1 did, she shared, and missing class was not as simple since it would involve standing up in the middle of instruction However Cecilia recalled her mother’s strength and words when she said, her mother said “You go, you go and I will excuse you, no questions asked.”

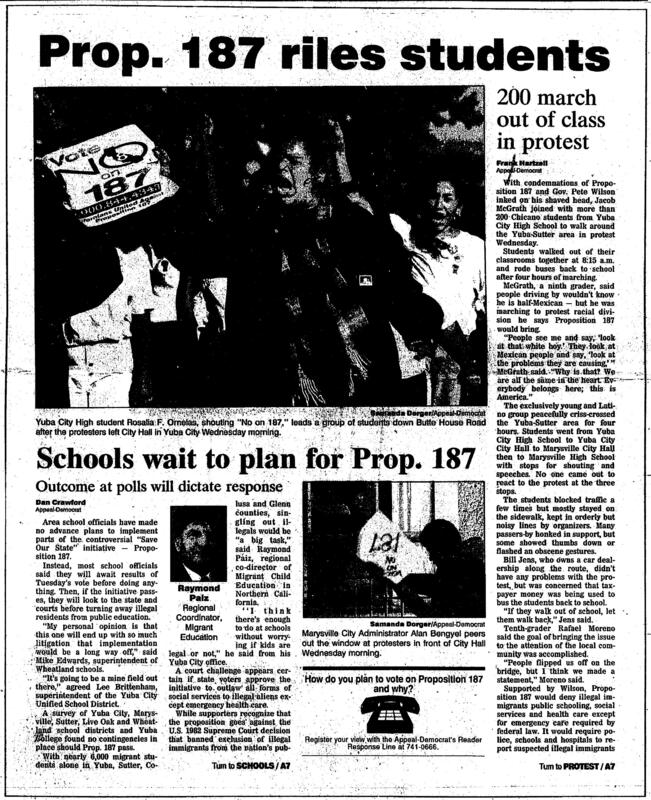

It was 10 o’clock when the walkout occurred. Cecilia described this walkout as more “organic” than the first. Organized by the students themselves, teachers were more visceral. One administrator even said, “If you are going to act like truants, then I am going to treat you like truants.” Cecilia persisted to walk out with several Yuba High students to city hall that day. Peaceful, she recalls a handful of counterprotesters. Featured left is the headline of the walk-out she participated in.

Cecilia did get punished for her involvement. She, like the others who walked out, had to attend school on Saturday. The Prop 187 protest was more than just lost class time. Cecilia, like many young latine in California, were concerned over Prop 187’s denial of primary and secondary education to the undocumented:

A Milestone, Not a Landmark

The legacy of Prop. 187 radically transformed California notably among the youth. Even after the initial surge of attention to the proposition, the complicated legal back and forth and length of LULAC vs. Wilson cemented its significance. Many current Latinx politicians, like Anthony Padilla, and activists cite Prop 187 as their entry into politics, meanwhile the Republican Party and any anti-immigrant coalition has had no significant presence in California, failing to occupy any statewide offices(2).

Although largely considered a landmark case in Chicano history, LULAC vs. Wilson failed to live up to the “overturn” (find a source) that many believed it to be. In fact parts of proposition 187 were in effect until 2014 (1 + 6) when the sections concerning criminal punishment for the manufacturing, distribution, and usage of documents were removed from the California penal code.

At its core, LULAC vs. Wilson disallowed state action on anything that had primary federal authority. The language of the second De Canas Test in the decison makes clear that no statewide statute could establish certain regulatory schemes since congressional action had already been taken in that “field”. LA times at the time reported on Clinton's denouncement of Prop 187(5). However while in Office Clinton passed the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRA) and Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRAIRA) , both federal regulations of immigration. In conversation with LULAC vs. Wilson (6), we see what was deemed as unconstitutional was not the treatment of the undocumented or the rights that belonged to them, but the level in which the legislation was introduced. Harsh legal policy that contributed to racialize and discriminate against the Chicano community could exist at a federal level.

Still, LULAC vs. Wilson was historic. In consequence, it gave voice to the Chicanos who felt their identities were being targeted. It still gratified the sentiment that this discriminatory law was illegal, although it wasn’t because denying services to the undocumented was wrong, and it wasn’t because policy having a disproportionate prejudicial impact on a specific ethnic group was wrong either. LULAC vs. Wilson should be remembered, but also criticized. Let’s keep this case in our memory as a landmark, but understand it as still a milestone.

-

“CA’s Anti-Immigrant Proposition 187 Is Voided, Ending State’s Five-Year Battle with ACLU, Rights Groups.” 1999. American Civil Liberties Union. July 29, 1999. https://www.aclu.org/press-releases/cas-anti-immigrant-proposition-187-voided-ending-states-five-year-battle-aclu-rights.

-

Denkmann, Libby. 2019. “California’s Prop 187 Vote Damaged GOP Relations with Immigrants.” Npr.org. November 8, 2019. https://www.npr.org/2019/11/08/777466912/californias-prop-187-vote-damaged-gop-relations-with-immigrants.

-

Galindo, Erick. 2019. “How ‘an Attack on Us Brown People’ 25 Years Ago Created a New Generation of Activists.” Projects.laist.com. November 8, 2019. https://projects.laist.com/2019/prop-187/prop-187.html.

-

Ibarra, Ana B. 2025. “Trump Wants to Break California’s Sanctuary State Law: 5 Things to Know.” CalMatters. January 28, 2025. https://calmatters.org/justice/2025/01/california-sanctuary-state/.

-

Lauter, David. 1994. “Clinton Attacks Prop. 187 at City Hall Rally.” Los Angeles Times. November 5, 1994. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1994-11-05-mn-58756-story.html.

-

Thurber, Dani. n.d. “Research Guides: A Latinx Resource Guide: Civil Rights Cases and Events in the United States: 1994: California’s Proposition 187.” Guides.loc.gov. https://guides.loc.gov/latinx-civil-rights/california-proposition-187#s-lib-ctab-25769023